Colourful history of a historian

It’s the late 1960s. On most Fridays, Michael Roberts would make his way towards Colombo from Peradeniya, recording equipment balanced at his feet and his bag filled with assorted clothes strapped to the back of his trusty scooter. Navigating the sharp curves and turns on his two wheeler, once in Colombo, he would spend his weekend sprinting from one interview to another. These interviews were long excursions down memory lane conducted with retired British and Sri Lankan public servants who had served in Sri Lanka (mainly in the Ceylon Civil Service), Sri Lankan politicians and notable figures and were at times, dense with details thoughtlessly relegated to the margins of history books. Sometimes completing four to five interviews for a weekend, Michael would then return to Peradeniya, laden with other people’s memories and anecdotes of an era gone by.

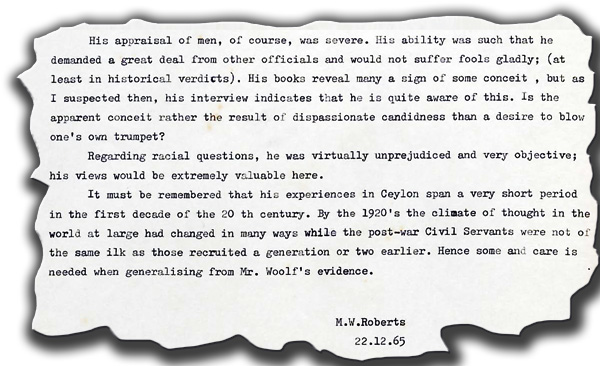

Extract from Michael Roberts’ interview with Leonard Woolf

A few decades later Michael reminisces about his oral history project and early beginnings in history and anthropology. He explains that this project was a humble attempt at archiving oral history and rescuing strands of Sri Lanka’s history from the memories of its aged civil servants. The project started off as an idea pitched to the Asia Foundation while studying at Oxford. In late 1965 and early 1966, Michael spent five months travelling all over England interviewing 30 – 40 British public servants who had served in Sri Lanka, including Leonard Woolf. The oral history project soon grew into an archive of 299 sound recordings of 154 interviews – some of which are accompanied with typewritten manuscripts, comments and bite sized fragments of historical gossip for the more salacious of history buffs.

“They were all very friendly and quite often I stayed with them. Because they were living all over England I had to travel even in winter, and most of them I taped with a big spool,” reflects Michael. These conversations provided a glimpse of their personal experiences as well as life in Ceylon and the politics of the Donoughmore Period, nationalism and land policies such as the land development ordinance of 1935.

Educated at the University of Peradeniya (“I sort of drifted into university,” he confesses) and a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford, Michael Roberts – although he is dismissive of labels – is a historian and anthropologist. Michael, who resides in Australia and was in Sri Lanka recently, has written and researched extensively on social mobility, identity, agrarian issues, urban history, caste, cultural domination, ethnic conflict and nationalism over the years. A quick search on the internet instantly yields countless articles and essays spanning these topics but it is his political writing and commentary on the last stages of the Sri Lankan war and aspects of nationalism, which has had brickbats, bouquets and epithets hurled in equal proportion. “If I analyze things in a certain way and reach certain conclusions, I have to present it – damn the consequences,” he says in a matter of fact manner, voicing his criticism for well-meaning but misinformed armchair intellectuals who don’t take into account basic empirical facts.

In Colombo last week: Michael Roberts. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Michael’s oral history project has now been digitized and the bulk of it can be accessed from the University of Adelaide’s digital library. Leonard Woolf’s interview for instance, is accompanied with PDFs of scanned yellowing typewritten transcripts as well as notes from his conversation with Michael in December 1965. Michael’s typewritten notes comment on Woolf’s unflinching candour with little regard for the recorder as well as his severe appraisal and judgement of the men who worked around him.

Upon Michael’s return to Sri Lanka and appointment as a lecturer at the University of Peradeniya, he continued the oral history project shuttling between the hills and the capital, adding local voices and well-known names to its growing archive.

Born to a West Indian father and Sri Lankan mother, raised in Galle and constantly mistaken for a Burgher, identity politics were inevitably intertwined in Michael’s personal life from his early days. Armed with a social scientist’s gaze, he reflects on his childhood and discusses how we go through life always constituting our identities, discarding or adding as we grow. “These identities come into play at different contexts but some become central,” highlights Michael. A teenager, for instance, might identify him/herself in accordance with the school they attend (for example, a Thomian, Royalist etc) while this may change into occupational identities (accountant, doctor, mother) or even ethnic ones.

Unconsciously, our conversation soon turns into the mildest of cerebral tussles. I’m curious about the history of the historian, while like a magnetic compass pointing north, Michael possesses the singular talent of directing the conversation into more political terrain. Apart from issues of identity, class and ethnic prejudice, Michael has explored facets of nationalism closely in his writing, along with analyses and results of the final stages of the war in his numerous essays and articles as well as on his blog (https://thupahi.wordpress.com/).

After a teaching stint at Peradeniya and research fellowships in the US and Germany, Michael moved to Adelaide with his family and taught at the University of Adelaide from 1977 – 2002. While moving countries (incidentally, a steel cabinet brimming with books also made the trip across the seas), he also made a shift in subjects, exchanging history for anthropology. “Moving sideways from history into anthropology meant developing my sociological and political science skills – so it was a kind of re-education as well. Because when you have to teach, you learn. You’re always learning when you teach, isn’t it? In fact, the best learning path is to actually be a teacher,” muses Michael. An Adjunct Associate Professor at University of Adelaide’s Department of Anthropology since 2003, Michael now devotes his time to writing on a range of issues as well as managing his blogs, Thuppahi and https://cricketique.wordpress.com/.

The high-pitched cries of a koel and the staccato hammerings at a construction site have been the soundtrack to our discussion as we delved into Michael’s life and research. Which brings us to the question – Why history? What propelled his fascination? Michael pauses and gives a characteristically pragmatic answer. “I think it’s a hobby, a passion […] People say you learn from history but I don’t know about that. I’m sceptical seeing power play and politicians and worldwide forces…”