News

NASTA hero Dengue’s Lankan nemesis

As intermittent rains bring forth the spectre of dengue, and fear grips people, especially parents, in an office off Kitulwatte Road, adjoining Kanatte, steady and solid has been the research on this dreaded disease. This is the reason why on the night of the prestigious Science and Technology awards being presented by none other than President Maithripala Sirisena himself, there was a pause.

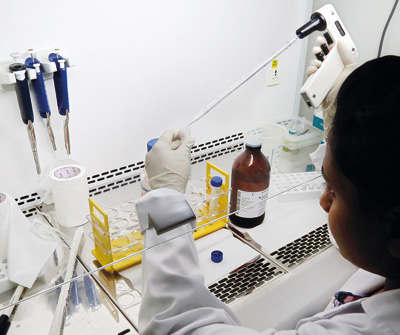

White blood cell separation from human blood at the state-of-the-art Genetech laboratory Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Usually, winners of the ‘National Awards for Science & Technology Achievements (NASTA Awards) – 2014’ would be up on the podium for their awards and back in their seats within a few minutes. But, for the ‘National Winner’ of the ‘Outstanding Science and Technology contributions having an impact on major national initiatives’ in the category ‘Harnessing Advanced Technologies through international collaboration’, there was a longer moment of glory, as President Sirisena whispered a query.

The Presidential query was about dengue which dominates the headlines of newspapers, while thousands seek help at hospitals across the country. It was directed at Dr Aruna Dharshan De Silva who has been dabbling in this important research for a long while. The National Science Foundation’s NASTA Awards to ‘Recognize the Role of Science and Technology in National Development’ had 13 categories, with 137 applications, from individuals and government and private sector organisations vying for them. There were National Award winners, including Dr. De Silva, in five categories, with five other categories being awarded Certificates of Merit.)

It is more recently that we met Dr. De Silva- Director and Senior Scientist of the pioneering Genetech Research Institute, at his office down Kitulwatte Road, to discuss his contributions in the field of dengue. He is living his belief that “the job of a scientist is to convince politicians” through sound research on the path to take for the benefit of the people.

Extracting DNA/RNA in the state-of-the-art Genetech laboratory

Backed to the hilt by Genetech, he has established an internationally-funded Research Programme to Study Dengue in Sri Lanka. His powerful standing within the international community as a Biomedical Researcher (his speaking engagements and research published in peer-reviewed journals being too numerous to mention) has gone a long way in this endeavour.

Currently he is Adjunct Associate Professor at La Jolla Institute of Allergy & Immunology, San Diego, California, United States of America (USA). With the state-of-the-art Main Research Laboratory and Tissue Culture Facility, with sophisticated machinery, the not-for-profit Genetech Research Institute, under the guidance of Dr. De Silva, has been able to engage in cutting-edge Biomedical/Immunology Research. This is while building the capacity of 10 local researchers.

Genetech Sri Lanka was started by the late visionary Dr. Maya B. Gunasekera, and is now headed by her husband, Dhammika N. Gunasekera. Although the current passion of Dr. De Silva is understanding how the human immune system responds to dengue, he is also looking into the strains of Burkholderia pseudomallei (which causes the Melioidosis disease) circulating in Sri Lanka, and the development of a diagnostic assay for the Chikungunya virus.

Elaborating on his dengue research work, Dr. De Silva says that it includes identifying the currently circulating dengue strains in Sri Lanka and studying their phylogeography, as part of dengue surveillance; studying why only some, and not others, become very ill when assailed by the dengue virus; and understanding how population genetics in Sri Lanka may play a role in severe dengue.

Before we get into the ‘science’ of it all, there is a discussion on the ‘molecular’ detective work which led to the finding that a new sub-type of Dengue Virus (DENV) 1 had surreptitiously crept in with the Chinese who had come to work at the Hambantota harbour and the Norochcholai coal power plant.

Dr. Dharshan De Silva: Dabbling in serious dengue research

He recalls, that in 2009, when he was researching the dengue strains, the number of people affected by the virus suddenly skyrocketed across the country. “There was a switch in the dengue strain from DENV-2 and 3 to DENV-1,” says Dr. De Silva, explaining that altogether there are four strains DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. Looking closely, the research team headed by him had found that there was a new DENV-1 sub-type circulating in the country.

Checking out the numerous possibilities, the closest link had been re-traced to China, where this type had been found in 2006. “We scrutinized the ‘molecular clock’,” smiles Dr. De Silva, adding that it tallied with Chinese workers coming into the country. This sub-type which had originally gone from Thailand (where it had let loose a massive epidemic) to China, had come to Sri Lanka, creating dengue-havoc, and then moved from here to Singapore and Pakistan.

The Research Projects of national importance conducted by Dr. De Silva are:

n Phylogeography and Molecular epidemiology of an epidemic strain of Dengue Virus Type 1 in Sri Lanka – under which the dissemination route of a virulent DENV-1 strain in Asia was traced, which would help in global control efforts. The study had been on patients visiting the North Colombo (Ragama) Teaching Hospital, who had been diagnosed as having Dengue Fever (DF) or Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF).

In 2009, a severe DHF epidemic occurred in Sri Lanka, causing 346 deaths. Earlier, Sri Lanka had seen mainly DENV-2 and DENV-3 predominating, with the former causing epidemics in 2002 and 2004. The 2009 epidemic had coincided with the arrival of a new DENV-1 strain, which had usurped the others as the pre-dominant strain.

His most recent award for ‘Harnessing advanced technologies through international collaboration’

“It is then that we found through phylogeographic analysis that the 2009-epidemic-causing DENV-1 strain may have travelled directly or indirectly from Thailand through China to Sri Lanka. After spreading within the Sri Lankan population, it travelled to Pakistan and Singapore,” says Dr. De Silva, commending the efforts of Dr. Karen E. Ocwieja of the University of Pennsylvania — School of Medicine, Philadelphia, USA, who pored over genetic data at the Genetech laboratory.

These findings have been published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene.

- The Dengue T-cell Project – this deals with T-cells (a type of white blood cell of vital importance to the immune system which fights infection), epitopes (an antigen recognized by the immune system) and peptides (biological molecules).

By using an advanced computer programme to which was fed dengue-strain information and HLA typing information, the research team had predicted possible dengue T-cell epitopes and 8,000 possible peptides. It had involved synthesizing and testing, using Sri Lankan healthy donor samples from individuals exposed to dengue in the past.

“Four-hundred biologically-relevant peptides in dengue, of which 300 were ‘unique’, not having been identified before, were found using advanced bioinformatics methods,” Dr. De Silva explains.The project was carried out in collaboration with Prof. Alex Sette of the La Jolla Institute of Allergy & Immunology, California, USA.

Several important journals, including the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), USA, published these findings.

- Dengue Population Genetics Programme – this is an ongoing global study of more than 8,000 dengue patients, with Sri Lanka contributing 1,200 samples of mild DF, DHF and controls. Begun in 2012, the high throughput genome analysis is underway.

“It will provide valuable population genetics data to understand whether some people are more vulnerable to DHF than others when infected with the dengue virus,” says Dr. De Silva, adding that the study is being conducted by Prof. Mark Loeb at McMaster University in Canada.