‘I did it for the country’

Nihal Fernando

Since the passing away of Nihal Fernando on April 20, many heartfelt tributes have been written by friends and associates who reminisced on facets of his life as a photographer, environmentalist, passionate lover of Sri Lanka and founder of ‘Studio Times’. His friends knew him to be a remarkable individual. Few people of such accomplishment nowadays are as self-effacing as Nihal was to the very end. So publicity-shy was he, that when his daughter Anu once asked him for information about himself requested by a friend (for an article) his short answer had been “Don’t want anything written on myself.” Hardly the most encouraging interview-subject for a prospective writer!

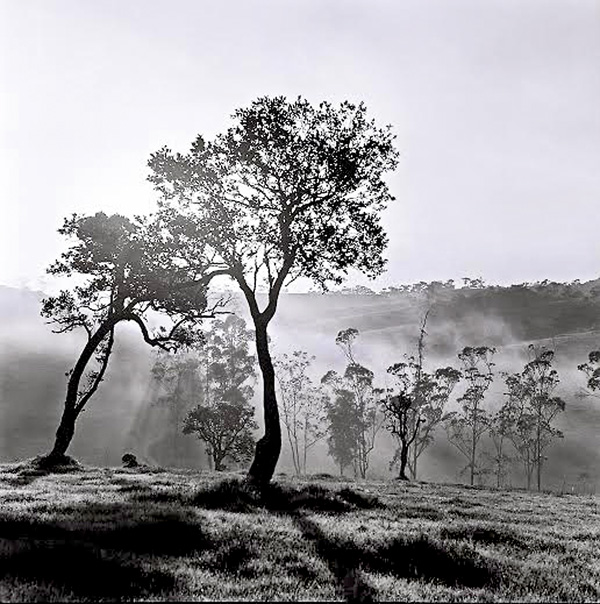

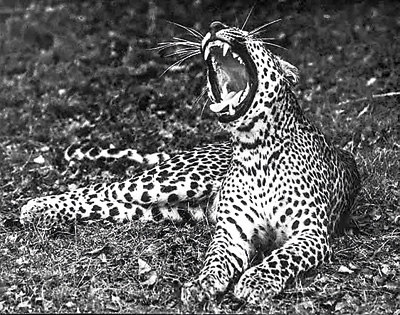

To those who knew him mainly as the author of some of the most outstanding wildlife and nature photographs produced in this country, the threads of his life story – some of which were gleaned by his persevering daughter and are related here – remain unknown to many.

Born on August 8, 1927 in Marawila, a coastal village south of Chilaw, Nihal grew up in a house on the edge of the beach ‘drinking fresh milk straight off the cows.’ His father Warnakulasuriya Weerasuriya Martin Fernando was a barrister in Marawila. His mother MaryAnne Ideline De Silva from Kalutara was the daughter of Domingo De Silva, crown proctor in Kalutara. As for his education his response to the question was ‘Nil.’ He first came to Colombo to attend St. Peter’s College aged six (“clutching my cat who escaped as soon as we got to the city. He must have been as disturbed as I was” he had recalled with humour to Richard Simon (Serendib- Sep/Oct 1986).

He did a one year course in photography at the London School of Photography (“Useless course.”) Asked what led him to photography he said he started photographing school groups with a borrowed camera to earn pocket money.

He did a one year course in photography at the London School of Photography (“Useless course.”) Asked what led him to photography he said he started photographing school groups with a borrowed camera to earn pocket money.

Borrowed from whom?

“A friend. Can’t remember who.”

What was the camera?

“A Rolleicord.”

Any photographers who inspired you?

“Can’t remember.”

Nihal’s first job was as a Press Photographer to the Times of Ceylon Group, working for the newspaper and also for the Studio which belonged to the Times Group. His photos were featured extensively in the Times of Ceylon Annual. When the Times Group decided to close the Studio, Nihal bought over the business and the goodwill in 1963. Studio Times was established as a limited liability company in 1970 with Nihal as Chairman. Asked about Pat Decker Nihal simply said “He was at ‘Cable and Wireless’ and I invited him to join Studio Times as he was a good photographer.”

Nihal’s wife Dodo Cooray who holds a BSc in Biology and Chemistry, is the grand-daughter of Sir James Peiris. A woman who cycled to University in a saree, she worked for Esmond Wickremasinghe and as a teacher at Bishop’s College. Their two children (and cousins – Nihal’s brother’s children) were given the ‘ge- name’ Weerasuriya as surname, dropping the Dutch-Burgher name ‘Fernando.’

Asked about awards, Nihal screwed up his face, Anu recalls: “We know that one of these Presidential Awards was offered to him (Deshamanya something – he won’t even tell us what) but he refused. Instead he suggested that it be awarded to Martin Wijesinghe – a Forest Officer at Sinharaja Rain Forest – a Sinhala speaking man with no formal education who knows the scientific name of every plant and creature in the forest.”

Asked about awards, Nihal screwed up his face, Anu recalls: “We know that one of these Presidential Awards was offered to him (Deshamanya something – he won’t even tell us what) but he refused. Instead he suggested that it be awarded to Martin Wijesinghe – a Forest Officer at Sinharaja Rain Forest – a Sinhala speaking man with no formal education who knows the scientific name of every plant and creature in the forest.”

He was honoured by St. Peter’s College Old Boys Union. “We know only because my daughter (aged about three at that time) suddenly turned up with the medal saying “Seeya gave me a medal for being such a lovely girl.” He had not gone for the ceremony and the medal had been sent home.”

“I know he has been honoured by some Environmental Forums too. He would have refused any awards offered to him and never even told us about it. His stock answer is: “I did not do it for any award, I did it for the country.”

Nihal’s activism to safeguard the country’s environment and precious natural heritage is well known. The most memorable instance was the movement instigated by him to save the Eppawela rock phosphate deposits from being mined by a US transnational company. The late Raja Goonesekera appeared free for the petitioners. “The resulting court case and enlightened ruling has made legal history not only in Sri Lanka, but also all over the world” wrote Rohan Wijesinha in The Island (08.08.07). “It is perhaps also the only time in conservation history that a National Trade Union has taken industrial action in support of an environmental cause” Wijesinha noted.

Sensitive shots: Capturing Sri Lanka’s beauty for posterity

In an obituary posted on its website the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka wrote:

“It is with profound sadness that we announce the passing away of one of the Wildlife & Nature Protection Society’s most outstanding members.”

“… We remember Nihal Fernando not only for his lasting photographic memorials of the beauty of this land, but also for the active role he took in ensuring their preservation for posterity. From the campaign to save the Sinharaja Rainforest, to several other causes, he gave not only his name, but also of his quiet wisdom and vast knowledge ….”

“His finest hour must surely have been the campaign to save Eppawala from the devastation of opencast phosphate mining. Such a project would not only have caused irreversible environmental damage to the area, but would also have led to the destruction of several sites of archaeological importance. In this campaign, he united peoples from diverse backgrounds and beliefs to save this precious place. For the first time in the Trade Union Movement, a half-day strike was called and a rally held in protest against the proposed ravaging of Eppawala. Trade Union leaders marched with Buddhist prelates, and the ordinary people of this country, to save a valued part of it. The court case, too, which stopped the mining, is even today, taken as a benchmark judgment on the value of protecting the environment for the greater good of the people.”

Other public interest litigation cases in which Nihal participated include the ADB Protected Area Management and Conservation Project, the Intellectual Property Bill and Water Reforms Bill. In the ADB case, “settlement was reached … to ensure that nothing would be changed without adherence to the laws of the land, and with transparency.” (Rohan Wijesinha, The Island, 08.08.07). In the case relating to the Intellectual Property Bill a Daily Mirror editorial (19.11.03) said: “the Supreme Court upheld this petition and because of it, millions of Sri Lankans for generations to come will have access to quality drugs at affordable prices.” (It’s not clear whether that particular public interest battle has been entirely won.) In the case of the Water Reforms Bill, the petitioners argued that the Bill, and consequent privatisation of water supply and distribution would violate the fundamental rights of the people.

“One thing can certainly be said of Nihal Fernando. Despite his many years of photographic adventure in the receding past, he fixes his eyes firmly on the future and the task that faces the next generation,” wrote Charitha Pelpola. ‘All my work has been for the children of Lanka,’ he says. ‘I hope it will help them on their way, as they become the leaders of the next millennium.’

“Fernando plants trees today, knowing that it will be his children’s children who will be there to harvest the fruit in years to come. He campaigns vigorously for the environment, trusting that if enough people listen, the spirit of conservation will inspire the young, ensuring a positive approach to safeguarding the environment. With the same foresight, he has produced a book that chronicles the trials and tribulations of the land he loves. It is a heartfelt appreciation of what we have now, and a statement of the responsibility that passes into the hands of the next generation. In a sense, it is a history of tomorrow.” (Serendib, Vol 17 No 3, May-June 1998).

Those who knew Nihal would not hesitate to concur with the unnamed author of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society’s moving tribute, which concluded saying: “With Nihal Fernando’s passing, the wild life and wild places of Sri Lanka have lost one of their truest champions, and Sri Lanka has lost one of its most faithful sons.”

| A lasting legacy The publications in which Nihal Fernando’s and Studio Times’ work has been featured are too numerous to list in full. These are in addition to Nihal’s and Studio Times’ own well-known books, from ‘The Handbook for the Ceylon Traveller’ (1974) to the most recent ‘Eloquence in Stone – the Lithic Saga of Sri Lanka’ (2008). Particularly noteworthy perhaps for its archival value was ‘Ceylon Yesterday, Sri Lanka Today’ by H.A.J. Hulugalle (Photography by Nihal Fernando and Pat Decker of Studio Times, Stureforlaget AB Sweden, 1976) which was presented to the delegates and heads of nations who attended the Non-Aligned Conference held in Sri Lanka in 1976. Art books included ‘Modern Art in Sri Lanka – The Anton Wickremasinghe Collection’ by Albert Dharmasiri (ANCL, 1988) and ‘The World of Stanley Kirinde’ by Sinharaja Tamitta Delgoda (Stamford Lake Press, 2005). Nihal’s sensitivity to nature no doubt informed his photography that appeared in works such as ‘The First 21 Years – The Singapore Zoological Gardens Story’ by Ilsa Sharp (1994) and ‘National Parks of Ceylon’ by Lyn de Alwis. Others whose books featured his work include Norah Roberts (Galle as quiet as sleep), Eva Darling and Albert Dharmasiri (Paynter), Vesak Nanayakkara (A Return to Kandy), R.L. Brohier (The Golden Plains), Ismeth Raheem (Catalogue of Paintings, Engravings and Drawings of Ceylon by 19th Century Artists), Raja de Silva (Sigiriya and its Significance, Diggings into the Past and other books), Gamini Punchihewa, Anurudha Seneviratne and Anne Ranasinghe. In the days of the Times Annual and the Observer Pictorial in the 1960s, the work of Pat Decker and Nihal Fernando was featured. ‘Loris,’ the journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka since 1936, has used Nihal’s images for several decades. Other Sri Lankan periodicals and newspapers also regularly use Nihal’s/Studio Times images. | |