Poetry coloured by Buddhist consciousness

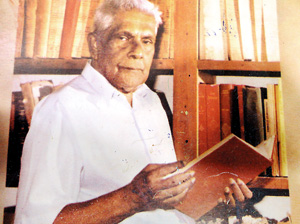

In the 1960s and 1970s when I was closely associated with the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, I had the good fortunate to interact with Wimal Abeysundera. I was deeply impressed by his breadth of learning and commitment to literature. He was fluent in Sinhala, English, Pali and Sanskrit. His deep knowledge of these languages as well as his easy familiarity with Buddhist literature had a deep impact on his literary creativity. Over a period of nearly seven decades, he produced poetry, critical essays, philosophical expositions, exegeses in music, of an exceptionally high order; he had published over one hundred books. A number of his works have been translated into foreign languages.

In this short essay, my primary focus will be on his poetry. Wimal Abeysundera is a celebrated poet of the Colombo School which had such a pervasive influence on Sinhala poetry from the 1940s to 1970s. The term Colombo Poets is capacious and covers poets of various dispositions and talents. Wimalaratne Kumaragama, who was in my judgment, the most successful Colombo poet wrote about the plight of the people living in the Wanni with great sympathy and discernment. Keyas (Sagara Palansuriya) excelled in poetic narratives. Sri Chandrarathna Manavasinghe, distinguished himself as a poet with rare lyrical gifts. Similarly, the strength of Wimal Abeysundera’s poetry resides in his imagination inflected by Buddhist literature and Buddhist thought. This inflection is a vital facet of his literary creativity. In his memorial lecture on Wimal Abeysundera, Gunadasa Amarasekera made a similar point.

Abeysundera’s poetry is marked by a deeply felt and sensitively experienced Buddhist consciousness. This operates at a number of levels of poetic apprehension. First, he has drawn liberally on Buddhist narratives; some of his poetic narratives are re-creations of traditional Buddhist stories. Second, he has written poetically about Buddhist places of worship, buildings, architecture with deep feeling. Third, in his poetic texts, Abeysundera has chosen to write about well-known figures, both ancient and modern, associated with Buddhism. Fourth, as a poet he was deeply interested in foregrounding Buddhist values, norms, outlooks that were directed towards the betterment of society and the enrichment of the individual self.

It is Abeysundera’s contention that as a consequence of the rapid spread of the consumer society and the increase in the velocity of globalisation, a crisis of values has been precipitated. This, according to him, has deep implications for society at large. One way of counteracting the harmful forces unleashed by the consumer society and globalisation is through the power of Buddhist values and Buddhist thought. Accordingly, he has constantly sought to invoke the power of Buddhist thought in his creative writings.

It is Abeysundera’s contention that as a consequence of the rapid spread of the consumer society and the increase in the velocity of globalisation, a crisis of values has been precipitated. This, according to him, has deep implications for society at large. One way of counteracting the harmful forces unleashed by the consumer society and globalisation is through the power of Buddhist values and Buddhist thought. Accordingly, he has constantly sought to invoke the power of Buddhist thought in his creative writings.

A concept that modern literary theorists frequently invoke in their exegetical writings is that of inter-textuality. What this refers to, broadly, is the way that writers makes use of, and press unto service, various idea, locutions, tropes found in earlier texts. Critics such as Julia Kristeva have explained the significance of this concept very convincingly. Abeysundera’s poems are full of inter-textuality. He draws on classical Buddhist texts with remarkable persuasive powers. Abeysundera’s poetic imagination takes flight on the wings of Buddhist spirit.

In addition to producing a substantial body of poetry, Abeysundera has also written a number of critical essays on poetry and the path chosen by Colombo poets. These essays contain many useful insights that would enable us to comprehend the natured intentions, agendas and investments of, Colombo poets more productively. For example, he makes the point that it was the customary practice of Colombo poets to compose poems consisting of seven or eight quatrains, and this was dictated by the needs of newspapers and magazines that increasingly began to publish poetry.

Wimal Abeysundera subscribed, by and large, to the poetic credo articulated both explicitly and implicitly by Colombo poets. At the same time, though, he chose to follow an independent pathway. His penchant for dealing with contemporary social phenomena and social issues such as the influence of computers on modern society and the importance of environmental issues as well as his desire to use Sanskrit words frequently in his poetry marks him off from most other Colombo poets. Moreover, instead of the eighteen syllable ‘samudraghosha’ metre adopted by the generality of Colombo poets, Abeysundera sought to experiment with form in some of his poetic compositions. For example, a poem like ‘suvayahana’ illustrates this predilection admirably.

When discussing Wimal Abeysundera’s poetry, I wish to draw attention to what I think are three central features in his poetry. The first is his deep humanism shaped and given form and direction by Buddhist thought. Hence I wish to characterise it as a form of Buddhist humanism. The concept of Buddhist humanism constituted a vitally important strand in the fabric of Abeysundera’s creative writings. In recent times, the term humanism has come under heavy fire, especially from those who subscribe to newer modes of textual analysis such as post-structuralism and post-modernism. In contemporary academic parlance, surprisingly, the term humanism has acquired negative connotations; indeed it has become a smear world.

Those critics of humanism assert that it is a Western discourse that places at the centre of its discussion the sovereign individual – the individual who is the originator of action and meaning. Wimal Abeysundera was fully aware of these criticisms of humanism and he maintained that humanism is not monolithic, that it does not have to be Eurocentric; his belief was that there are different forms of humanism and that Buddhist humanism was one such distinctive form. What he sought to do in his writings is to dramatise the relevance and importance of Buddhist humanism to contemporary society.

The second is his indubitable sensitivity to the Sinhala language. He was a deep believer that a writer can be effective and live up to his or her expectations only if he or she is able to listen to language patiently and sensitively. Wimal Abeysundera possessed this skill in abundance.

Let us for a moment consider the Sinhala poetic language. The metre, rhythms, sound patterns inextricably linked with the Sinhala language have to be carefully made use of by the creative writer and sensitively analysed by the critic. The rhythm, to take one example, is not only a vital part of the auditory imagination; it is also integrally linked to the linguistic meaning produced by the text. Indeed, it is the desire for linguistic meaning that powers the rhythm. It can be asserted justifiably that poetry seeks to privilege the materiality of language; it encircles it. The materiality comprises sound patterns, shape of words, and aural movements as they interact within the imaginative universe of the poem. It is evident that a poet like Rev. Sri Rahula was able to exploit these resources with great skill and competence to the full to invest his poetic works with an exquisite lyricism and a fund of radiant meanings.

Third, the idea of tradition is extremely important. Wimal Abeysundera was a writer who had a profound understanding of the Sinhala literary tradition. His deep knowledge of Sinhala, Pali, Sanskrit and English as well as his profound understanding of Buddhist thought enabled him to situate the Sinhala literary tradition in its proper discursive context. It has to be noted that the concept of tradition is very elusive and has a multiplicity of interpretations depending upon one’s own intellectual vantage points and investments. It is integrally connected to such ideas as modernity, rationality, history, memory and ideology. A tradition permits us to construct a narrative of the past, the present and the future on the basis of a certain past dealing with a certain present.

The concept of tradition is normally regarded as a polar opposite of modernity. Although there are clear differences and points of antithesis between the two, recent scholarship serves to suggest that tradition and modernity are mutually constitutive. It is to his credit that Abeysundera was able to understand the deeper significance of tradition. He recognises the fact that it evolves, enlarges itself even as it preserves certain identifiable elements from the past. An understanding of tradition is needed to navigate the intricate and demanding literary debates of our time.

What is needed is a lengthy and more nuanced re-reading of the Colombo poets as a cultural phenomenon worthy of our closest attention. And in that effort, the poetry of Wimal Abeysundera whose intellectual and emotional centre is Buddhist humanism should figure prominently.