Rage, rage against the dying of the light

For Christmas, my friend Janaki gave me a book called ‘Ammonites and leaping fish’ by Penelope Lively. This, according to the author, was ‘her view from old age’, the ripe old age of 80. Early this year, someone sent me the late Anne Abayasekera’s essay on being old.

Reading both these excellent bits of writing, I think of two things. First, of a quotation attributed both to George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde, ‘Youth is wasted on the young’, and second, my own rueful self-knowledge that one does not have to be 80 to be old. On the shady side of fifty, I am acutely aware of old age creeping through every pore in my skin.

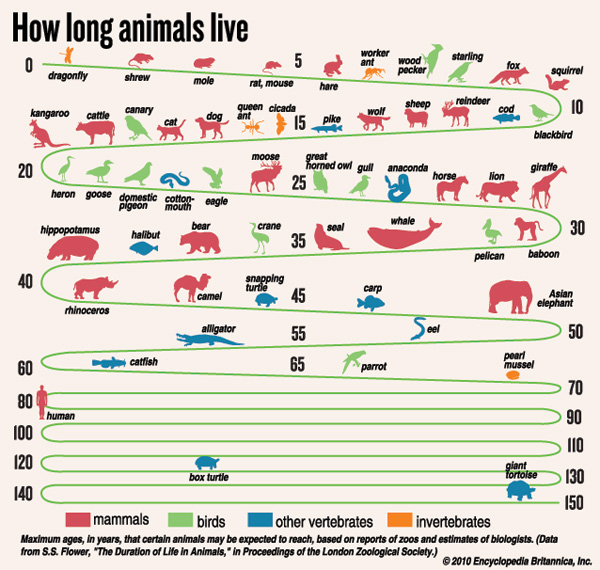

Figure 1. The life spans of different species ( © 2010 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.)

I recall wondering as a teenager why my father would ensure that the light fell precisely so on the canvas before he started painting. What was he on about, I thought? Now, following the light like a sunflower and furiously adjusting lamps, I know exactly what he felt. It’s been two decades since my arm stopped being long enough for me to read without glasses.

First your eyes let you down; then your bones. I recently saw a hilarious clip of a DVD of the British comedienne Miranda Hart trying to sit down on the grass at a picnic and find a comfortable position, all the while muttering “When did that stop being possible?”

With age, gravity has one impact on certain parts of the body such as bosoms and chins, which hurtle downwards, and another on waistlines and hips, which spread sideways. The sun, which was irrelevant during childhood and adolescence (which of us did not fry during the annual sport meet?), suddenly becomes an enervating annoyance.

Frighteningly, energy suddenly and acutely becomes seriously limiting. The days of youth — of staying up all night to cram; answering a written exam in the morning; sitting for a practical exam in the afternoon; going out to celebrate the end of university exams; and falling into bed a full 24 hours since you last slept — is a thing of the Pleistocene. The mere recollection makes me want to lie down for a nap.

So what precisely is ageing?Senescence — or ageing — is the condition or process of deterioration with age. (The term senescence’ is derived from a Latin word senescere which means to grow old.) In biology, senescence is also known as the loss of a cell’s power to divide and grow. (The cell, in biology, is the fundamental building block of any living organism.)Primary cell cultures — human cells differentiated into cells of different systems (such as muscle cells or neurons, the cells of the nervous system) taken out of humans and grown in vitro in the lab — have a finite life, i.e., they do not replicate indefinitely. This limit of proliferation after a period of normal growth is called the Hayflick limit, after the scientist who discovered this.

Part of the amazing complexity of the human body is its ability to repair itself. When we cut ourselves, the skin heals. When we fracture bones, they knit into place, with a little help from a doctor. A gaping tooth socket, left bare by a tooth extraction, is eventually filled by the gum that grows in its place. If pathogens enter our bodies, a suite of certain types of white blood cells attack them.

At the cellular level, damage is normal, and occurs every day of our lives. Oxygen, which is essential for almost every human function, tends to react with other essential molecules such as proteins and change their structure and function. Environmental toxins such as smoke, pollutants such a pesticides, and even alcohol, also wreak havoc on normal cells. However, daily and hourly these cells are self-repaired: damaged proteins are cleared out the cells, digested to smaller units and reassembled. Even our DNA repairs itself. This process of self-repair is called tissue homeostasis, which is the functional and structural maintenance of cells, organs and systems in our bodies. It is as if we have, within our bodies, a multitude of mechanics, electricians, carpenters and plumbers fixing every fault as soon as it is noticed.

With senescence, this ability to self-repair is slowed down and eventually stops. At a cellular level, vital components of life — such as proteins and DNA — are damaged and not repaired. Proteins such as collagen and elastin (both of which form connective tissue, the cellular glue of our bodies) slowly accumulate damage and lose the ability to contract and expand, resulting in wrinkled and saggy skin. In the lens of the eyes is another protein — crystallin — that provides transparency to the lens and also helps in refraction. With age, these proteins lose their structure through the accumulation of oxidation products and the lens clouds up, forming cataracts.

(There are many other theories for ageing but space prevents their discussion here.)

When does ageing start? Philosophy would maintain that one is destined to die the day one is born. Even some biologists maintain that ‘biological ageing is a continuum that starts at birth and ends at death’. Most biologists would divide a person’s or living organism’s life span into three phases: development, maturity and senescence. Development is the period of growth. Development is defined to end at maturity when all biological functions — such as reproduction — are at their optimum. The end of maturity signals the beginning of malfunction in cellular repair. Senescence, is then, the post-reproductive phase, when cellular repair is impaired and as one scientist writes,generally ‘manifested as the decline of vitality and function.’

Life spans themselves vary vastly across different species, and among humans, across different areas and different economies of the world. The average life expectancy (the statistical measure of how long a person will live) of a Sri Lankan was estimated in 2012, by the World Bank to be 74 years. Iceland has the highest life expectancy in the world of 83 years, followed by developed countries such as Britain, Australia and Spain (82 years); India is at 66, and at the other end of the spectrum, Swaziland and Sierra Leone have life expectancies as low as 49 and 45 years respectively. The longest human life span on record is that of Jeanne Louise Calment, a Frenchwoman who lived 122 years and 164 days.

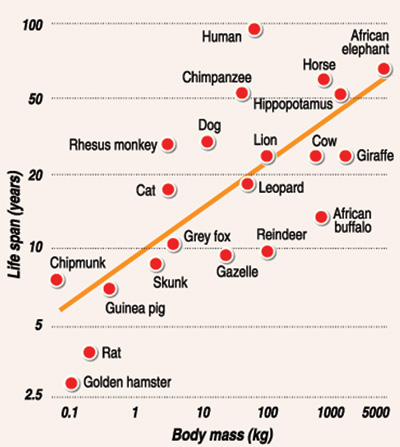

Figure 2. The life spans of different species correlated with body weight

The Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinuslongaeva)found in the southwest United States, flies off the scales of extremes in longevity living up to about 5,000 years. Sturgeon — a fish species — is also known to age very slowly, to about 200 years. Another fish — the rockfish Sebastes — also exhibits negligible senescence, growing and reproducing for a hundred years. Rapid senescence is observed in mayflies, whose development phase is very prolonged and may last up to five years, but whose mature, reproductive phase lasts for a few hours or few days (depending on the species), before they die. Another example of rapid senescence is the Pacific salmon, which is born in freshwater, grows into a juvenile fish, and then migrates to the ocean. Two to five years after hatching, it migrates back to the freshwater stream of its birth and begins to spawn. Typically, the fish ages and dies within two weeks of spawning. In the plant world, some Asian bamboos (Phyllostachys) grow for several decades to a hundred years, then flower and die within one season.

The bulk of living organisms, however, exhibit gradual senescence. A mouse lives for about three to four years, chimpanzees about 50 and elephants, about 70 years. In general, for homeothermic (‘warm-blooded’) animals, larger animals live longer than smaller animals. This correlation has been observed for decades now, and is associated with survival: smaller bodies tend to lose heat faster than larger bodies. Hence, it is better, in an evolutionary sense, to develop, mature and reproduce quicker, rather than expend energy on keeping warm.

Humans, as can be seen from the graph in Figure 2, have a much longer life span than expected for their body size. This can be attributed to our brains, which have made possible medical advances such as eye lens, various joint and kidney replacements that extend longevity.

Another anomaly is observed with social animals such as primates, who live longer than expected for their body size. Also in this category are bees and wasps (again social insects), as well as the naked mole-rat of Africa,a peculiar rodent with very littlefur, which lives its life completely underground. These mole-rats live in large colonies of up to about 80 individuals and live for two to three decades, unlike their relatives, mice, which live onlythree to fouryears.

Scientists have found that there is plasticity in the onset of senescence. In the example of the Pacific salmon described earlier, preventing reproduction (through castration) delayed ageing and death. The worm Nereis matures at two years, stops feeding, reproduces and dies. Experiments that transplanted a cluster of nerve cells from immature adults into these senescent worms doubled their life spans.

Another candidate for experiments is the free-living round worm Caenorhabditiselegans. When environmental conditions are favourable, the worm reproduces and grows in four larval stages to become an adult. When conditions are not good, the worm enters into a non-feeding, stress-resistant stage called the dauer stage, which can last long. Scientists have found that certain genes that control the regular life cycle can be switched off, inducing dauer formation and boosting longevity by a factor of five. More interestingly, these researchers found that a high glucose diet switches the gene back on, decreasing longevity.

In fact, in laboratory mice, restricting caloric intake to 60-70% of the regular diet has been shown to increase their life spans by 50%. Biogerontology — the study of the biology of ageing and longevity— currently examines how experimentation in other species helps our understanding of human senescence. Medical researchers have shown that continuing and routine exercise delays the onset of some age-related diseases. Yet others advocate a controlled diet.The increase of human life spans over the last century is a testament to the vast improvements in medical knowledge and improved delivery of health support. With the advent and rise of molecular biology, gene therapy, currently used for treating some serious hereditary diseases, may become a tool for anti-ageing, who knows?

Whatever science is attempting currently, it may be good for us in Sri Lanka to learn a lesson from biology — that social animals live longer. We have lived too long in a climate of selfishness, distrust and discontent. The time is ripe for change.

One final comment: age, ultimately, is a state of mind. I am always reminded of my aunt who went on safari in Kenya last year at the age of 84, and spent days in a jeep, travelling hundreds of kilometres on bad roads. I am also reminded of a near-octogenarian friend who just returned from a trip to Sikkim to see the Himalayas.

As Mark Twain wrote: ‘Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.’