The voice of protest

Vihanga Perera is a study in contrasts. On the internet and in the media, he is a forceful voice and a happy dissenter of mainstream opinion. As a published author he is confrontational and prone to writing well received if somewhat inflammatory text. In person he’s laidback, amusing and genuinely, thoroughly baffled as to why his work is misunderstood and occasionally even “not understood at all”.

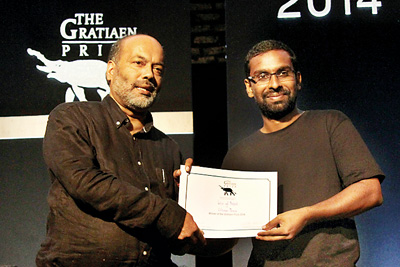

Chairperson of the Gratiaen Trust Dr. Walter Perera presents the Gratiaen Prize 2014 to Vihanga Perera at the ceremony held at Park Street Mews on Friday, June 11. Pic by Indika Handuwala

The latter doesn’t seem to matter as much, of course, when seen in the light of his Gratiaen win last week. Vihanga’s poetry collection ‘Love and Protest’ earned him the prestigious literary prize which is awarded every year to outstanding works of literature in English produced by a resident of Sri Lanka. This is his third time being shortlisted for the Gratiaen award. Vihanga’s winning speech was short – he thanked those who had to be thanked and casually urged everyone to buy his book (available at leading bookshops islandwide). Winning the Gratiaen is a big deal, he tells us. “As a writer if you have a channel that you can use to push your work out there then you have to use it.”

Delivering the judges’ comments, chairperson of the panel, Dr. Sonali Deraniyagala praised ‘Love and Protest’ as a “powerful collection of poetry dealing with the contemporary.” The poems were “distilled with nuance and clarity,” she noted “and they were expressive and uniquely Sri Lankan.” ‘Love and Protest’ is a collection of 50 poems on love (largely) and contemporary topics that Vihanga penned over 2013 and 2014, compiled by Paw Print Publishing.

Vihanga is no stranger to literary circles in Colombo, and Kandy in particular where he grew up. He schooled at Kingswood College, going on to study for an Honours Degree in English at the University of Peradeniya. Today- although he has other professional commitments- he blithely describes himself as a full-time writer. “I write pretty much every day,” he says. “I’ll write something new or I’ll rework an old manuscript but this is what I do.”

Vihanga Perera

The 31-year-old author began writing in his teens, starting out with “the usual”; he recently rediscovered 133 poems written about a romantic interest at the time, he grins. “There has definitely been somewhat of a jump from what I was writing as an 18-year-old to what I was writing as a 20-year-old. I feel that my work has become less abstract and more defined over time.”

Vihanga was first published at 21. Over the years publications (both poetry and fiction) have been many; ‘The(ir) (Au)topsy’ in 2006, Stable Horses (2008), Busted Intellectual (2010) are a few of his published works. While the critics have not yet taken up their pens for ‘Love and Protest’, commentary on his earlier work has been admiring but occasionally unabashed in criticism, and you can’t help but feel Vihanga just doesn’t care. But sometimes it stings, he says. Does he ever take it into account? “Criticism of my work has rarely been helpful,” he says. “I think I’ve been around for too long for it to have a real impact.”

He looks back on his work written during the early twenties with a certain amount of nostalgia. Readers and critics have occasionally lambasted Vihanga’s work for being “difficult to understand,” he tells us “and I think after a while that must have stayed in my subconscious because these days my work is more conceptually grounded. With maturity comes craft, I suppose.” It’s not ideal, he adds. But shouldn’t published writers make it their mission to be accessible? “Look there are two types of writers. Those that are more mainstream- and they should definitely concern themselves with it (accessibility) – and those who are more experimental.” If you’re in the latter group then catering to the mainstream is a hindrance to creativity, he believes. “Ideally we’ll meet at the halfway point, me and the reader.”

He has his admirers aplenty, mind you. Vihanga’s blogs ‘Fish on the Sand’ (for his poetry) and ‘In Love with a Whale’ are very popular (of the latter he says-“people take that blog way too seriously”) and from when he first published his work many critics have lauded his braveness and honesty. In 2010 Malinda Seneviratne, last year’s Gratiaen Prize winner, called him a “prolific writer” adding however that he had “a tendency to write in political preferences”. His commentary on politics in particular is what has thrust Vihanga’s work into the limelight, and he himself will tell you that some of his most notable work was “after 2009”, when every English writer picked up their pen in Sri Lanka. “We need more honest writers,” he says adding, “I recently read Ayathurai Santhan’s Gratiaen entry (Rails Run Parallel) and enjoyed it because he looks at the local reality during a period that is spoken about very rarely by Sri Lankan authors.”

Vihanga doesn’t attach too much importance to his work, however. “When you’re a writer working in the English medium in this country you’re shielded somewhat,” he observes. “You’re reaching a very small audience with the language. Writing in Sinhala or Tamil-that’s where you have real impact.” He may pick up his pen to write in the Sinhala language sometime in the future, he says, although he’s not yet sure what he’ll do. Right now, post Gratiaen, Vihanga has several projects to keep him busy. He’ll take his time before the next book gets published. After all “once I’ve delivered a baby,” he says gravely “I can’t deliver a mouse.”

The Gratiaen Prize 2014

Shortlist: Vihanga Perera, Love and Protest (winner)

Sandali Ash, Rao’s Guide to Lime Pickling

Ayathurai Santhan, Rails Run Parallel

Quintus G. Fernando, Celibacy Factor

H.A.I. Goonetilleke prize for best English translation: Vijitha Fernando, Time Rebounds (a translation of Keerthi Welisarage’s ‘Kalasarpa’)