Hooked on the hackery

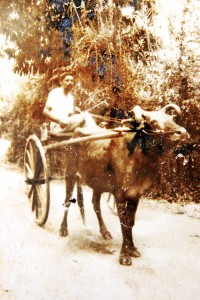

Pulling out a black and white photograph from an album, K. Wilson aka “Poddaiya” shows a picture of himself riding a thirikkal (hackery), in the prime of youth.

Then comes his twin brother K. Piyasena whom they call “Lokkaiya” carrying a few framed photographs of the thirikkal races his sibling took part in, back in the day.

The photographs take us back in time, to the time when thirikkal (hackeries) were commonly used. Though seldom seen in society today, for the three siblings K. Wilson, K. Piyasena (the 72-year- old twins) and 82-year-old K. Karunasena from Ganemulla, Kesbewa, the thirikkalaya at home is still very much part and parcel of their lives.

This thirikkalaya is over 80 years now and still in running condition, says Poddaiya showing us a grand hackery parked outside their house.

Poddaiya racing during Avurudu this year and left, in the good old days. Photos by Indika Handuwela

“My father got it made from a skilled thirikkal- maker who lived in Panadura those days,” says Lokkaiya.

Poddaiya is an ardent thirikkal racer who started racing at the age of 20, his siblings tell the Sunday Times adding that it was in the 1960s that he first started riding a thirikkal, with Sundays set aside for riding practices.

“There are five of us in the family – three boys and two girls. While my twin brother was busy working in his garage and my brother Karunasena took to government service, I was the one who chose farming in the family. This is what pushed me into thirikkal riding and racing. I eventually got addicted to it,” Poddaiya says.

Kapila: Continuing the tradition

The brothers are so passionate about thirikkal riding that their leisure time on Sundays was spent riding around the village in the hackery, they say.

A skilled racer, it was Poddaiya who took thirikkal racing seriously. Even in his old age, he still continues to participate in the annual Avurudu races and over the years has won over 100 races including the championship in Piliyandala for 10 consecutive years.

“This picture is from a race I took part in Meegoda in the 80s….the thirikkalaya in front, is mine. This is me, accepting the certificate after winning the competition,” says a proud Poddaiya showing us the other photographs in his collection.

According to him, thirikkal racing is risky and practice is needed to do it. “Imagine riding at a speed of 45 Kmph… mind you there are no brakes in this,” he smiles.

The racing bulls tied to the hackery too have to be well trained according to him, and the bull is given continuous training for a year at least.

Even with years of experience, Poddaiya still counts on divine protection prior to undertaking a race by lighting a lamp in the Ganewatte shrine close by, he says.

Although thirikkal are rare now, according to Karunasena, a considerable number of hackery owners still exist in areas like Homagama, Kaduwela, Kesbewa, Pilyandala, Dompe, Wennapuwa, Marawila and Pugoda.

“In the good old days, thirikkal and buggy carts were a popular mode of transportation. Every house in Ganemulla had a thirikkal, or a buggy cart I remember. Even the lawyers, doctors, teachers and clergy travelled in these. I remember how bridal parties were taken in them. We used to light a kerosene lamp and travel in the nights for emergencies,” Karunasena says adding that the bulls used for paddy harvesting were used to pull the hackeries.

“Rural folk survived on the paddy field, cows, and thirikkal or buggy carts,” Karunasena says adding that thirikkal racing is a traditional pastime of the peasant community passed down from generations.

The brothers also recall the days when they used to travel to Kaduwela from Piliyandala to meet a famous hackery racer who lived there.

Members of this thirikkal family spoke of the misconceptions about thirikkal racing.

“People say it is cruelty to the animals. We do not agree with this because not everyone treats the animals like that. This is one way of saving the animal from going to the butcher because racing bulls are taken care of, for 10- 15 years. Racing bulls have to be strong and healthy to take part in the races, so they are given proper nourishment as well,” they insist.

“There is no need to pinch the animal’s tail or beat it with a stick during the race. Naturally those who see this kind of treatment to the animal tend to dislike hackery racing. But if you talk to the animals in their language, that is more than enough,” says Poddaiya.

Continuing the family legacy over the past 12 years is Karunasena’s son Kapila. He follows the family tradition by going on a thirikkal ride every Sunday. Every year he goes to see his uncle take part in races although he does not participate due to a physical injury.

Inspired by his uncle, his nephew Hemal Perera has also learnt to ride the hackery and has begun organising a thirikkal race in Ganewatta every year for the past four years. “I want to make sure that this tradition will be sustained. As kids, we had the privilege of seeing this, thanks to our family background. But it is not so for the present generation,” says Hemal adding that if they are to preserve this age-old form of transportation, Hackery rallies should be organised more often for public viewing, targeting the tourists as well.