Sunday Times 2

Senake Bandaranayake: Scholar, art critic and institution builder

View(s):Professor Senake Bandaranayake, the prominent Archaeologist and Emeritus Professor, University of Kelaniya, passed away in his sleep, after a long illness, on March 2, 2015.

With a liberal mixed Buddhist and Christian upbringing and a radical youth orientation, Professor Senake Bandaranayake blossomed as a leading scholar in Sri Lanka when he opted for Archaeology as his academic discipline and his most dedicated lifetime preoccupation. His scope of scholarly inquiry as an enlightened academic however was not confined to the narrow precincts of orthodox archaeology. Among many other life interests, he ventured into art criticism, both ancient and modern, contemporary social justice issues, critical cultural studies and some of the most intriguing theoretical issues such as ‘internal versus external dynamics of socio-cultural development.’ His greatest lasting contribution to university education, as a culmination of these pursuits, was focused on institution building for research and postgraduate studies. The University of the Future and the Culture of Learning (2007) was the epitome of this venture.

With a liberal mixed Buddhist and Christian upbringing and a radical youth orientation, Professor Senake Bandaranayake blossomed as a leading scholar in Sri Lanka when he opted for Archaeology as his academic discipline and his most dedicated lifetime preoccupation. His scope of scholarly inquiry as an enlightened academic however was not confined to the narrow precincts of orthodox archaeology. Among many other life interests, he ventured into art criticism, both ancient and modern, contemporary social justice issues, critical cultural studies and some of the most intriguing theoretical issues such as ‘internal versus external dynamics of socio-cultural development.’ His greatest lasting contribution to university education, as a culmination of these pursuits, was focused on institution building for research and postgraduate studies. The University of the Future and the Culture of Learning (2007) was the epitome of this venture.

Remarkable Career

Born in 1938, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Senake Bandaranayake pursued his school education at St. Thomas College, Mount Lavinia in late 1940s and throughout 1950s, in a post-independence socio-political context. Thereafter, he continued his university education in Britain beginning early 1960s, as his parents moved to London on retirement. They mostly lived in the fashionable Holland Park area of London, with Victorian architecture and landscape. It is possible that his love for architecture originated there.

After obtaining a bachelor English honours degree from the University of Bristol, he opted to move to archaeology as a specialized field at the prestigious University of Oxford. His pursuits in archaeology were prefaced by a Diploma in Anthropology, at the same university, the training in which enriched him immensely in socio-historical interpretation of his and others’ archaeological findings later. His postgraduate studies proper consisted of a preliminary thesis on “The Vaulted Brick Image-Houses of Polonnaruva” for which he obtained a B.Litt. (1965) and a D.Phil. (1972) for a dissertation on “The Viharas of Anuradhapura.”

Senake was a Renaissance man, influenced by the best traditions of the West and the East. He had a radical orientation in London as a youth, influenced by the student movements in late 1960s, particularly in France, and associating himself with students (from Sri Lanka). His later radicalism, however, was more in the spheres of culture, art and archaeology. He was a close friend and benefactor of Ivan Peries, a founder of the ’43 Art Group and a leading Sri Lankan painter along with George Keyt and Justin Deraniyagala. Ivan Peries, brother of renowned film maker Lester James Peries, also lived in England at this time. This orientation of art critique became more fruitful with Senake’s association with Manel Fonseka, his future wife and lifetime partner. One of the finest products of their joint efforts was Ivan Peries Paintings: 1938-88 (1996).

With the completion of his D. Phil. and publication of his first book, Senake left Europe in 1974 to return to his homeland, making a 7,000 mile car journey across Europe and Asia, visiting and studying architecture and archaeological sites along the way. He joined the University of Kelaniya in 1975 as a Senior Lecturer in Archaeology. His ascent on the academic ladder thereafter could be considered customary for a person of his calibre. In 2003, he retired as a Senior Professor and became associated with the University as an Emeritus Professor. He was a Head of the Department and a Vice Chancellor of the same university. His national and international involvements were impressive and noteworthy. He was the founder-Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology (1986-1997), and was appointed Ambassador of Sri Lanka to France and to UNESCO in 1999. He was also Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner in India and Ambassador to Bhutan. He was the undisputed founder of the National Centre for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences (NCAS) under the auspices of the University Grants Commission (UGC) in 2006.

Radical Archaeologist

Senake has left an indisputable imprint as a radical archaeologist, both in the fields of discovery and interpretation. He made a remarkable contribution in periodizing early Sri Lankan history and identifying the period between 1000 – 500 BC as the time when the islanders moved from stone-age food gathering to the making of pottery, sedentary farming, basic irrigation, wet rice cultivation and iron technology. Then he uncovered the period of remarkable growth where complex social and political institutions evolved associated with the higher forms of religion and relatively advanced literate civilization even before the Common Era (AD). He never denied however the interaction between the internal and the external in such developments. However his major contribution concerned the ‘theory of internal dynamics’ as he proudly declared. The location of the country was a major spring for this dialectic in his opinion. As he said, ‘wide open to the sea and continually impacted by external contact, its evolution was also fundamentally an internalized process within the territory.’ As the territory, he meant the Island as a whole but with quite a variety of differentiations. (See Continuities and Transformations: Studies in Sri Lankan Archaeology and History, 2012, p. 14).

He also opined that in what he called the late historical period (13th to 19th c.), “Sri Lanka also exhibits changes very similar to those of the Southeast Asian states with the dominance of centrifugal forces, the emergence of multiple polities, and the manifestation of proto-capitalist tendencies.”

Most impressive were his efforts to apply these dialectics of interplay between the ‘external and the internal’ to understanding the evolution of ethnicities or ethnic communities in Sri Lanka, deconstructing some of the orthodox views on ethnic and state formation. These interpretations are useful particularly today in unravelling the ethnic conundrum allowing people to understand their histories without myth or animosities, and as part and parcel of the same evolution. It is on the basis of these archaeology-related historical studies that he ventured to demolish the Aryan-Dravidian myth in the Sinhala-Tamil ethnic debate in Sri Lanka. Submitting a research paper to the Social Scientists Association in 1979, he said, “What the Aryan-Dravidian misconception represents in the Sri Lankan (as in the Indian) context, is the way in which purely modern misinterpretations are projected into history and play a key role in providing historical sanction for the ethnic self-identity of the two major nationalities which inhabit the island, the Sinhalese and the Tamils.”

As the doyen of archaeological studies at the University of Kelaniya he transformed the teaching and learning of archaeology from a purely classroom based discipline to one that combined theory and practice, which in turn had some influence on the teaching and learning of archaeology and related subjects in the country. He helped to create conditions where undergraduates studying archaeology were able to do field and practical work (such as survey, excavations, plan drawing and draughtsmanship, laboratory analysis and conservation). He initiated a strong tradition of undergraduate research. Undergraduates were encouraged to do work that often involved the recording and ordering of hitherto unknown data and gave much emphasis in the curriculum and examinations to practical work and research dissertations, a practice now followed fairly widely in university departments.

Art and Architecture

Senake Bandaranayake had an abiding interest in contemporary painting as well as its ancient forerunners from times immemorial. He also had a rare vision of contemplating architecture as a form of art. His exploration into ancient architecture was motivated, in this sense, largely by his motivation for art although not that explicit at times. He saw various forms of architecture as distinct forms of art. He started his first substantive publication, Sinhalese Monastic Architecture (1974) by saying in its introduction, “The architecture that a society creates is a substantial and organic expression of its inner life.” And further on he said “In the absence of any definitive chronology of Sinhalese art and architecture…for generations to come, any systematic attempt to study the known remains has to evolve a framework capable of adjusting itself to new material and new interpretations.” (p.3). He thus not only placed art and architecture on the same plane but also talked about the need for new, I must say artistic, interpretations. That was his orientation whether interpreting ancient monastic architecture or Geoffrey Bawa’s contributions to modern architectural landscape. In appreciating Bawa at his first memorial lecture Senake said, “He did for contemporary architecture what the ’43 Group did for painting, Martin Wickremasinghe for the Sinhala novel, Ediriweera Sarathchandra for theatre, Lester James Peries for film.”

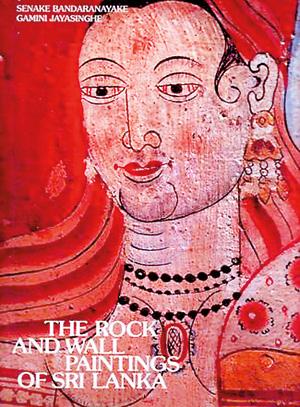

In the case of The Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka (1986), he ventured into the very beginnings of so far obscure Vedda rock art. Perhaps his effort was to trace ‘our own tradition’ in that important aspect of visual arts without neglecting the ‘give and take’ from outside. Professor Ashley Halpe, in a review, appreciated his effort as “the first comprehensive work in this field,” because up until then the records were scattered or missing. Earlier, students or researchers had to forage through monographs, obscure articles in defunct journals or few books, if at all. Now almost everything was available in ‘one stop shop.’ This valuable book of 300 pages includes 97 black and white and 169 coloured illustrations. Some of the analytical chapters by Senake Bandaranayake are on, “The Evolution of a Pictorial Tradition,” “Early and Middle Period Paintings” and “Late Period Murals,” all illustrated by Gamini Jayasinghe’s brilliant photography.

With the collaboration of his wife, Manel Fonseka, Senake ventured to evaluate the contributions of the Art Group ’43. Contrary to the prevailing opinion of that time that ‘they represented a western and an alien trend in paintings,’ the duo showed that the ’43 Group represented an “invention of a modern and yet distinctively local tradition — a mode of indigenized modernization, of great originality and authenticity.” Their assessment of the group was largely in line with that of Geoffrey Beling (Chief Inspector of Art in Schools, 1932-1967). Senake had a special liking and patronage for Ivan Peries’ paintings. As he noted “Best known for his symbolic and expressive landscapes and seascapes, and his subtle, almost musical, use of colour and tone, his works range from portrait studies, figure compositions and abstract collages to large, panoramic panels and delicate miniatures in acrylic and watercolour.” It is fair to say that in Senake’s many ventures, the woman, Manel Fonseka was behind him.

Institution Builder

I had a short but a close association with Senake Bandaranayake when he was the Chair of the University Grants Commission’s Committee on Post-Graduate Education in my capacity as the Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Colombo during 2003-2005. Even before, I recollect his vision to set up a centre of excellence in postgraduate studies and advanced research when I met him first at the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute in 1995. His model was the Academy of Social Sciences in the Soviet Union of that time which is not unknown even today to countries like Australia or United Kingdom. However his vision was more towards practical tasks of training and capacity building for young university lecturers in the fields of humanities and social sciences which were particularly lagging behind the other fields of studies in the country. He also envisioned that such an institution could become a ‘think tank’ for policy innovation and policy making in the country.

His role in institution building, however, was much broader or wide ranging. First it was the Department of Archaeology as the Head where he was serving and then the University itself when he was the Vice Chancellor. He also had a major role to play in creating the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology (PGIAR) and developed it to a high level as its founding Director, introducing hitherto neglected disciplines into the study of archaeology such as settlement archaeology and archaeobotany. His contribution to the Cultural Triangle Programme under the auspicious of UNESCO was unequivocal. He was a Director General of the Central Cultural Fund in its formative teething period. As the Archaeological Director of the Cultural Triangle Project at Sigiriya (and also Dambulla) for a period of nearly 18 years, he built on the work of four previous archaeologists and here his philosophy of institution building took the form of Conservation which involved a high degree of preservation, minimal intervention, rigorous maintenance, and maximum protection of the natural environment.

His last but lasting contribution to institution building was the creation of the National Centre for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences (NCAS). As its website says, “The Centre was set up after few years of discussion and study at the University Grants Commission (UGC), initiated by Professor Senake Bandaranayake, involving senior professors in the relevant fields, to address the needs and requirements of human resource development, advanced research studies and academic publications in humanities and social sciences as well as related fields.” Since its founding in 2006, with Bandaranayake as its first Chairperson, the NCAS has awarded over 200 scholarships for university teachers in the relevant fields to pursue their postgraduate degrees (mostly PhDs) in the country or abroad. This is in addition to research training, seminars and publications that the NCAS conducts under its auspicious. I was a witness to his particular contribution as NCAS’ second Director and third Chairperson.

It was undoubtedly due to hard work and long hours in archaeological sites that Professor Senake Bandaranayake had to encounter serious health issues quite prematurely in his life almost immediately after his retirement from the university service. He was however immensely blessed to leave this world peacefully in his sleep three months ago on 2nd March.

(Dr Laksiri Fernando is former Senior Professor in Political Science and Public Policy, University of Colombo, and former Director of the National Centre for Advanced Studies).