Sunday Times 2

Doors to the Colours of Paradise

View(s):Photographer, artists’ best friend, and maestro di color Dominic Sansoni has dedicated his life and work to the pursuit of beauty, writes Stephen Prins

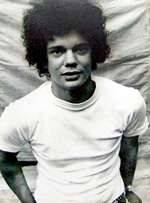

Now and Then, Here and There: Dominic Sansoni. Colour photo: Isabella Sansoni

Doors Scraped. Peeled. Unfinished. Old, colonial doors. Closed but wide open. Waiting to open. Tap. Push. Enter.

Open Sesame. Before you is a vision of rainbow radiance. The colours are overwhelming. The vision is for real. The interior is not any interior but a stronghold, a treasury for the preservation and disbursal of colour in all its paradisal splendour.

The colours hang in swathes from the roof and roll out, tumble, spill all over. The message is: Come and glory in all this colour. Colour is good for eye, head, heart. Hues go from hot to cool. Papaya, banana, lime, avocado. Oleander, hibiscus. Kingfisher, peacock. Ruby, tourmaline. Mountain stream. Jungle.

Photographer-entrepreneur Dominic Sansoni, the magician behind the visual fantasia, is not to be seen. Like any good weaver of spells, he is around but not readily visible. If he is not in front of you, minding the BAREFOOT business, he is in his lofty den, tinkering with images, talking to artists, travellers, and traders in beautiful objects and concepts. The den overlooks the BAREFOOT garden, gallery and alfresco café. Colourful, tasteful, crowd-pleasing Sansoni creations.

Many years ago, Barbara Sansoni, the artist and founder of BAREFOOT, vendor of superior handloom fabrics and a lot more, handed over the reins to her capable, talented second son. She must be deeply satisfied with where he has taken the family business.

Many years ago, Barbara Sansoni, the artist and founder of BAREFOOT, vendor of superior handloom fabrics and a lot more, handed over the reins to her capable, talented second son. She must be deeply satisfied with where he has taken the family business.

Our visits to BAREFOOT, from the ’80s on, were more to meet the peripatetic photographer-proprietor and hear about his ongoing work than to shop for linen napkins. The visits were a year apart, as we were living overseas, so it was fortuitous to meet Mr. Sansoni, and disappointing to find he had left that morning for Mauritius, Yemen, Singapore, Australia. It meant another year’s wait.

But there were other reasons besides meeting the owner for pushing through the doors of No. 704, Galle Road, Kollupitiya. We were propelled in that direction out of a kind of necessity. When we left Sri Lanka in 1986 to work in the far Far East, the war was already under way. The news from home was unrelentingly depressing. Like thousands of expat Sri Lankans, we would land at Katunayake with a baggage of guilt – guilt at not being here, on the ground, grieving year-round with everyone else as the stricken land shot and bled itself dry. You looked around and your heart sank. Christmas had no glitter. Colombo had no cheer. Buses carried time bombs. Cars exploded. VVIPs were being blown up. This would go on for all the 22 years we were away.

BAREFOOT, meanwhile, sustained a brave, bright front in those grim years, doing what it could to dispel the gloom. You pushed open the doors and your heart lifted at the sight of all that joyous colour. The message was that it’s not all bad, mad and sad in Sri Lanka.

On the lucky occasions we did meet the roving, restless proprietor, the encounter was a laugh a minute. Dominic Sansoni is delightful company, tonic to the soul if you feel low. We talked about anything, everything: art and artists, photography and photographers, black, white, colour. Would Lionel Wendt, that genius of chiaroscuro, have embraced colour if he’d lived long enough? When would we make that pilgrimage to the hills to place flowers on the tombstone of Julia Margaret Cameron, the great pioneering Victorian photographer who’s buried in the garden of St Mary’s Church, Bogawantala?

On the lucky occasions we did meet the roving, restless proprietor, the encounter was a laugh a minute. Dominic Sansoni is delightful company, tonic to the soul if you feel low. We talked about anything, everything: art and artists, photography and photographers, black, white, colour. Would Lionel Wendt, that genius of chiaroscuro, have embraced colour if he’d lived long enough? When would we make that pilgrimage to the hills to place flowers on the tombstone of Julia Margaret Cameron, the great pioneering Victorian photographer who’s buried in the garden of St Mary’s Church, Bogawantala?

Dominic would show us his private collection of Keyt, Ivan Peries, Manjusri, and Wendt originals. Art is his altar.

Creative pleasure

An encounter with Dominic Sansoni is a creative pleasure. He is like undiluted caffeine, extra-strong.

It was in the internationally eventful year 1970 that we first sighted Dominic Sansoni. We looked up and there he was – a fair, voluble, hyper-energetic 14-year-old, with a head of black curly hair, in T-shirt, denims, sneakers. He was 20 steps ahead, striding along with his buddy Stefan Abeysekera, his senior by seven years. He did most of the talking while Stefan listened.

Behind the two of them was Stefan’s La Bamba set, ourself bringing up the rear. At what point Sansoni had attached himself to La Bamba set is not clear. What was clear was that Dominic dominated. He was the youngest and he commanded attention.

Sansoni the adult has not effaced that first impression at 14. The ebullience is still there, and the momentum seems to have increased. He also continues to maintain his 20 steps-ahead lead. As a teen, Sansoni was untethered. His parents Barbara and Hilden left him to his own devices, and his older brother Simon was always away. Hilden Sansoni was retiring and went to bed early, while Barbara was travelling the world pursuing inspiration for her art and her fabrics business.

Stefan Abeysekera and Dominic Sansoni bonded like twin brothers, age gap regardless. Stefan was Older Brother, Mentor and Guiding Spirit to young Sansoni. The evening-to-late-night pounding of La Bamba pavements continued until Cousin Stefan left for Australia three years later, in 1973.

One night, walking up Layard’s Road, young Sansoni raised his voice – in prayer or song or out of teen excess and exhilaration, we would soon know.

“Jesus Christ, JESUS CHRIST,” he cried, “Who are You? What have You Sacrificed?”

Superstar

He was roaring an aria from “Jesus Christ Superstar”, the talk of America and Europe at the time. As the proud possessor of the first copy of the rock-opera to enter the country, brought by Barbara from the UK, young Sansoni invited The Gang to hear the Superstar album in his home.

A procession of long-haired rockers in denims and one nerd in schoolboy white filed into Dominic’s domain, an avant-garde piece designed by Danish architect Ulrich Plesner and built in the Sansoni backyard. You hopped up an unprotected flight of steps and emerged in a wide, open space with a roof and no walls. In a far corner was a brick-concrete block covered with mattress, sheets, pillows. At our host’s insistence, we made ourselves at home. We lay on the bed and listened to Webber, Rice and birdsong between tracks. Dangling from the rafters, inches above our nose, was a hanging garden of empty liquor bottles strung up for fun on long white cords. In the event of monsoon winds, the swinging bottles would sing a clinking song of Johnny Walker-Beefeater-Smirnoff-and-Baileys. In another corner was a bathroom with two doors marked “Ben-Hers” and “Ben-His.”

You leaned over and looked down at a goldfish pond in the garden, just as Herod chided the captive Christ:

“So if You are the Christ -

You’re the great Jesus Christ,

Prove to me that You’re no fool,

Walk across my swimming pool.”

When the album was done, we filed down to the back patio where there was Dutch furniture and art on the walls. One mostly green watercolour was signed “Dominic”, 1962. The artist was six when he executed his study of a garden and a driveway in lime and “gotukola” green. One of the Gang made fun of the picture. Perhaps he felt the fancy frame was too good for the artwork. “You call that a painting?”

The artist was quick to defend his juvenilia. “Look a little harder,” young Sansoni said, defensive and surly. “It should show you a very good sense of colour.” Well said. That was our thought too. The picture was worthy of its frame, and worth displaying.

“What do you want to do when you grow up?” we politely enquired, in a tone typical of an older teen talking to a much younger teen. ”I want to be a photographer,” was the growled reply.

And then we were back on the road, the Early and Late Teen Wanderers of La Bamba, strutting, striding, shambling towards our variegated futures. After Stefan disappeared, the Gang broke up. Some followed The Guru to the Southern Hemisphere, and Dominic, who felt as if his ship had lost its anchor, started to drift. He travelled around the world, bankrolled by Barbara, the indulgent mother he addressed as “B”, or “Bee”. By age 17, he had seen the world and was ready to settle down. He went to his mother’s other home in Oxford and took a course in photography at the Ruskin School of Art.

From that point on, our encounters were scattered and years between. We pretty much lost touch, until BAREFOOT moved into our neighbourhood in Kollupitiya. Over the years, we’d seen the Aladdin’s Cave that is the Sansoni enterprise grow and grow. It started out as a cavern, a hollowed-out house at the top of 8th Lane. Then the cave went deeper, dropping a level to accommodate books and more fabrics, artwork, stuffed toys, winsome bijouterie, ingenious handcraftsmanship, furniture, woodwork and bubbly bric-a-brac.

Then the cave dropped another level and debouched in a garden. More exciting spaces opened up for a dining-drinking area, a loggia, and a gallery to showcase new art, not-so-new art, and art of the future. There is always music and inspiring people to meet in and around the garden. After dark, there are parties to launch a new exhibition, a new artist, a new book. Party effervescence is the prevailing mood on Sansoni terrain.

Pure chance

The photographer with the steady hand, keen eye, and unerring instinct for mood, moment and composition, says he does not feel 100 per cent responsible for his photographs. “My work depends on what catches my eye. It’s pure chance. I try to move fast before the chance goes away. The rest is Kodak film and the camera.”

Others insist it is Dominic Sansoni first, film and camera second.

Mr. Sansoni is an artist, one of high calibre. He has a clear unflinching eye for what’s worth saving and what may safely be trashed. He also has astonishing range. His exploring instincts takes him due North, East, South, West – as far as his energy, Range Rover and air ticket will take him. He has spot-on, 360-degree vision for what’s beautiful.

Sansoni in his shop is like a grown child with a playbox. He waves his hand, wields crayon and paintbrush and conjures up wonders. The shop for him is like one of those wooden toys with multiple compartments; in each box, each room, he spins out his multichromatic fantasies.

Sansoni’s panoramic take on all things visual includes talent-spotting. He zeroes in on gifted, undiscovered, drifting persons, holds them gently by the arm and takes them indoors, bringing that talent to the world’s notice.

Sansoni’s generous spirit embraces everyone. Fellow artists are his favourite company, especially those in need of special attention. That means he’s endlessly adopting folk and making them part of the family. It’s a big family.

Visits usually find Sansoni in a state of perpetual motion. If he is not hurtling around to check on his shop or click his camera, he is surfing the Net for friends, art, beauty. One afternoon we found him fussing around with a sepia lady dozing in a hammock. He was using the computer to erase ugly scratches on an old image he was preparing for a Powerpoint presentation. He was to give a Colombo Biennale lecture about the wealth of Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim, Malay and Burgher tradition to be found in photograph albums mouldering away in almirahs and wardrobes. He was urging the public to bring out these treasures and archive them as a way of bringing the country together, after decades of divisiveness.

During those years of annual Christmas visits from overseas, we never left the country without a gift stamped Sansoni. One year, during the long war, it was a soldier on duty with his AK47. Another year, it was the Reclining Buddha in Polonnaruwa, the most serene image in the world. Still another year, it was a holy man in South India. And so it went. All these images beautified our home in the Far East.

And then, suddenly, overnight we were surrounded by dozens of Dominic Sansoni images.

This was at the Woodside Art and Performing Arts Gallery, a dream space come true that we brought into being during our time in Hong Kong. For three years, in an amateur, recreational capacity, we ran a venue for art and photography exhibitions and chamber music concerts. This was in the grand hall of a British colonial redbrick mansion on a mountain in a country park. The gallery flourished for three years, attracting local and international artists and musicians. The last event was in December 2001, and the farewell exhibition was a display of Sri Lankan images by Dominic Sansoni. The photographs were widely admired and had many takers.

An American woman, a specialist in art and photography, took us academically through the images, pointing out their compositional values. When we told the photographer back home that we had been treated to an in-depth analysis of his work, and this was what the New York lady had to say about his pictures, Sansoni scratched his head. “I had no such notions when I took those photos, or when I take any photos,” he said, bewildered but flattered.

That taught us a little lesson about Art. That there may be more to a work of art than even the creator imagines. The artist does what he must do and leaves it at that. It is for the audience, the critic, to see the subtleties and tie-ins. Perhaps the artist sees all this anyway, in a flash, in the subconscious. Who knows? Even the artist is at a loss for an answer.

Dominic Sansoni celebrated his 59th birthday on July 24. His astrological sign is Leo. According to the zodiacal chart, the Nemean Lion is “dominant, determined, energetic, extrovert, a natural leader”; he is also “sensitive, kind, openhearted, extremely generous.” And: “Amazingly creative.”

All these traits are listed or hinted at in this birthday tribute, which was completed before we consulted the Leo chart.

At 59, Mr. Sansoni is on the cusp of his next decade. May it be filled with even more Colour, Beauty and Adventures in Art.