Gallipoli: Today’s peace dotted with poignant memories

I am seated by the large window in my 5th floor hotel room in the Turkish city of Canakkale, looking out over the picturesque Dardanelles Waterway at the hills of the Gallipoli peninsula across the water.

I am seated by the large window in my 5th floor hotel room in the Turkish city of Canakkale, looking out over the picturesque Dardanelles Waterway at the hills of the Gallipoli peninsula across the water.

Gallipoli lies on the European side of the Dardanelles – close to where 3,000 years ago the ships of the Achaean Greeks arrived to cross the strait and begin the Trojan War. The ruins of Troy (called Truva by the Turkish) lie in Canakkale province on the Asian side of Turkey, some 30 km southwest of where I now am.

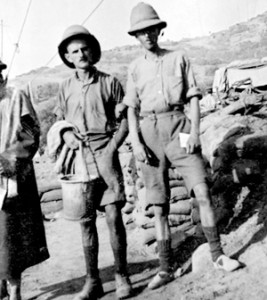

Two soldiers of the Ceylon Planters Rifle Corps who acted as Lt.Gen. William Birdwood’s bodyguards throughout the Gallipoli campaign

It was in these now tranquil waters that during the First World War, on March 18, 1915, a fleet of British and French battleships with powerful names like Irrestible, Inflexible, Queen Elizabeth and Charlemagne tried to force their way through the strait towards Constantinople. Bombarded from the Turkish shore batteries on either side of the strait they sailed into a newly laid minefield – and by the end of the day three of their big battleships were sunk and several others crippled. “The day,” according to Britain’s official naval historian Captain Cecil Aspinall, “ended in complete failure for the Allied fleet.”

It is hard today to picture those dreadful scenes of violence as I watch a couple of oil tankers steadily and peacefully sailing through the straits and the sun languidly setting over the Gallipoli hills.

Yesterday I had taken the ferry across the strait to the town of Eceabat on the other side and visited the century old battlefields of the First World War on the Gallipoli peninsula. In April 1915 Britain decided to land a force of soldiers, for the most part colonial troops (the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps or ANZACs, drawn mainly from Australia and New Zealand but with a small number from the Indian subcontinent) onto the west coast of Gallipoli with the intent of capturing the peninsula and moving north to conquer Constantinople, the prize capital of the Ottoman empire.

The ensuing Gallipoli campaign was a costly failure for the Allies. By the time they evacuated their troops in December 1915, they had lost almost 45,000 men – 8000 from Australia, 2800 from New Zealand and 1400 from India. The Turks paid a heavy price for their victory – over 86,000 Ottoman soldiers lost their lives. One regiment, the Turkish 57th Regiment, lost almost all its men during the Gallipoli war – there is a magnificent monument and memorial cemetery here to remember their sacrifice.

My visit to Gallipoli coincided with the remembrance ceremonies that took place on August 6 this year at the Lone Pine cemetery. One of the most famous battles of the campaign – the Battle of Lone Pine – was fought exactly a hundred years ago, on August 6, 1915, between the ANZACs from the colonies and the Ottoman forces from not only Turkey but also other parts of the Ottoman empire. On a battlefield where the trenches were no more than 60 to 150 metres apart the Turks lost about 7000 dead or wounded, the ANZACS more than 2000.

Many of those who died on Gallipoli were buried en masse and have no known resting place. There are well maintained cemeteries today at Lone Pine and at the 57th Regiment cemetery. The stones here do not mark the actual graves – they are merely gravestones that document the names of those who were killed here.

At the southernmost point of the peninsula, Seddulbahir, is a massive monument, the largest memorial on the peninsula that is visible to all ships that approach the mouth of the strait. Called the Canakkale Martyrs’ Memorial it was built by the Turks in 1950 as a tribute to the 86,000 who died here defending their homeland. Two kilometres away is the French cemetery (stark black crosses for the Frenchmen and secular linear markers for the Senegalese colonial troops who died with them) and at various battlefield sites on the peninsula are no less than 14 ANZAC cemeteries.

I discovered that among the ‘British’ troops engaged in the Gallipoli campaign were men of the Ceylon Planters Rifle Corps (CPRC), a unit composed chiefly of British planters. On October 27, 1914 their contingent of approximately 230 sailed from Ceylon to Egypt, where it was attached to the 1st Battalion Wellington Regiment (part of the ANZACs) and deployed as garrison troops in the Suez Canal area until March 1915.

The writer at the Australian ANZAC cemetery at Lone Pine

In April 1915, when the ANZACs were re-organised in Egypt for the invasion of Turkey, over 100 members of the CPRC contingent were granted commissions in the British and British-Indian Army. The remainder were attached to the 1st ANZAC Corps, functioning as a bodyguard to the ANZAC Commander Lieutenant General William Birdwood – who is quoted as saying “I have an excellent guard of Ceylon Planters – they are such a nice lot of fellows.”

The CPRC contingent landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula between April 25 and May 1, 1915 at the Ari Burnu beach-head (now known as Anzac Cove). Several of them are known to have died in Gallipoli but their graves are unknown. The lands around the Dardanelles have been fought over for over four thousand years.

Today, the memorials and gravestones here are a poignant reminder of the young men on both sides who fought and died on this barren peninsula. But I could not help thinking, as I looked on the well maintained headstones in the Gallipoli cemeteries, of that poem The Battle of Blenheim by Robert Southey that I learned many years ago as a schoolboy:

‘They said it was a shocking sight

After the field was won;

For many thousand bodies here

Lay rotting in the sun;

But things like that, you know, must be

After a famous victory’