Writing to the beat of Bombay

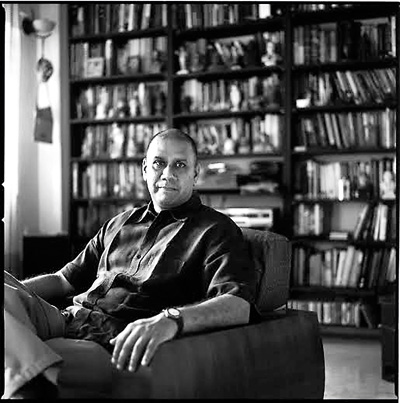

View(s):Naresh Fernandes arrives for his session at Cinnamon Colomboscope covered in sweat. It’s a hot day but Fernandes has been on a brisk walk around Slave Island. He is fascinated with the parallels he sees between this city and his own – the frenetic development, the deepening class divide,and the contradictions inherent in democracies that can conduct elections smoothly only to have their liberal institutions fail their citizens. He is filing all this and more away, some to inform his sessions, some for the stories he will commission about Sri Lanka but mostly, one gets the sense, to satisfy his own curiosity.

A well-known Indian journalist and editor, Fernandes has made a career of keeping his finger on the pulse of Mumbai – except he prefers to call it by its old name, Bombay. His two books – Taj Mahal Foxtrot and City Adrift – are both about this place. One is a history of how the Taj Hotel in Bombay hosted a remarkable jazz scene, and how pioneers like Leon Abbey (who brought the first African-American jazz band to Bombay in 1935) and Teddy Weatherford(Louis Armstrong’s pianist),would inspire the Goan musicians who accompanied them. The result would be a sound whose influence would stretch as far as the cinemas of Bollywood.

A well-known Indian journalist and editor, Fernandes has made a career of keeping his finger on the pulse of Mumbai – except he prefers to call it by its old name, Bombay. His two books – Taj Mahal Foxtrot and City Adrift – are both about this place. One is a history of how the Taj Hotel in Bombay hosted a remarkable jazz scene, and how pioneers like Leon Abbey (who brought the first African-American jazz band to Bombay in 1935) and Teddy Weatherford(Louis Armstrong’s pianist),would inspire the Goan musicians who accompanied them. The result would be a sound whose influence would stretch as far as the cinemas of Bollywood.

Then there is his other book, City Adrift, a slender yet ambitious biography of Bombay for which the author draws on histories both personal and national. He writes of how the linking of the islands, though representing a great logistical challenge, helped transform a ‘malarial swamp into a global city.’ It would grow into a cosmopolitan metropolis – which Mahatma Gandhi called the “hope of my dreams” –robust enough to resist the communal tensions that accompanied Independence and Partition. But Bombay is no longer the city it was, and Fernandes is clear-eyed about the tensions that have threatened it in recent decades.

City Adrift is one of a series of such biographies about Indian cities, and Fernandes said he was left to make up his own mind about how he would tackle the project. “I’m that kind of strange paradox in which one part of my family are insiders in a city in which almost everybody is an outsider, but my father’s side of the family came in 1947. So we have these two parallel stories going, the Bombay story of the migrant and the Bombay story of the settler and we know how often in Bombay history those two sides are at war.”

Fernandes is already at work on another book that will also explore Bombay’s past and present, but this he says is hopelessly delayed due to the demands on his time placed by Scroll.in. Launched in 2014, the digital daily of which he is an editor, has rapidly gained a wide readership in India. “It’s been astonishing how quickly you can reach vast numbers of readers – if we had to physically distribute we’d never be at the numbers we are at,” says Fernandes, adding that being online has had other rewards.

“Traditionally people have said that Indian readers are interested in three things, the ABC: astrology, Bollywood and cricket.” However, the thing about digital media the team found, was that a seemingly inexhaustible flow of reader metrics was always pouring in – and these figures were revealing that people were interested in much more than the ABC. “We found that people will read a challenging piece on the rural employment guarantee scheme in Chhattisgarh at 3,000 words, just as long as it was a well-written story and well told. We are astonished constantly at the things that people are reading and delighted and encouraged by this.”

They chose to focus more on reportage rather than opinion pieces, and found readers approved. For one of their earliest successes, Fernandes’ colleague Supriya Sharma chose to get on a train prior to the 2014 elections and travel some 2,500 km. She would cross seven states, filing stories regularly as she went. The idea, says Fernandes, was not to talk about the politicians but how people saw politics, what government meant to them and how the system had supported or failed them. “We wanted to shift the focus from the big institutions to seeing how it plays out on the ground.”

Fernandes, who has worked in newspapers, wire services, T.V. and magazines, says the goal for the 12-member team that produces Scroll.in is to work at the pace of a wire service with the context of a magazine. “Some days we achieve it, some days we don’t.”

Though Fernandes is putting in 16-hour work days to feed the beast, he describes the end result as “astonishingly satisfying.” In 2015, the team was recognized as the ‘News Start-up of the Year’ at the Red Ink Journalism Awards. And for a relatively young publication, Scroll.in does punch above its weight. “Last week for instance a minister in Mizoram (Lal Thanzara) resigned because of a story we broke,” says Fernandes, adding with a grin,“Ok, it’s a small state, but still it means something.”

As the interview wraps up, he says such successes remind him of his early days in journalism. “My first job was at the Times of India during the Bombay riots (of the early 90s), and that was a really remarkable period for me, for even as my city was going through so much trauma, you saw that when you wrote something the government and the administration took action almost immediately…that when you had these vast numbers of readers behind a publication, people in power were forced to listen, that the power of the press was not a cliché,” he pauses, “I have sometimes thought over the 20 years or so since, that we had lost that.” That he was proved wrong is a comfort both to Fernandes and to his readers.