Raising a cuppa to a legacy

View(s):There are two antiquated words which embody Sir Thomas Lipton’s entrepreneurial spirit and commercial success – chutzpah and gumption. You need both to make it in the business world and Sir Thomas Lipton had large quantities of both these qualities. There are traces of it visible in his early life.

Lest we forget: A memorial to a pioneering name in the tea industry. Pix by M.D. Nissanka

The youngest of five children, education was a luxury the working class families in the slums of Glasgow could ill afford. A callow youth restless with ambition, Lipton vaulted through a series of odd jobs. The earliest glimpse of his enduring spirit was seen in young Tom Lipton’s – he was barely in his teens at this point in time – bold request for a 25 per cent increase in his wages, while working as a shirt pattern cutter. His employer’s prompt answer was abrupt and discouraging – “You are getting as much as you are worth and are in a devil of a hurry asking for a rise” – but Lipton didn’t falter.

Built by Lipton: The Dambatenne planter’s bungalow

If James Taylor pioneered commercial tea plantations in Ceylon, it was Sir Thomas Lipton who turned Ceylon tea into a household brand. By the time Thomas Lipton arrived in Ceylon 1890, he was unrecognizable from the uncouth lad who had dared to ask his boss for a raise. He had made his name in the grocery trade and was known as a hard worker. He had climbed to the upper echelons of society and was a rich man with little interest in politics, art or societal gild. It has been often said that if Thomas Lipton was a millionaire, his foray into tea made him a multi-millionaire.

Purportedly on his way to Australia and also recovering from the deaths of his parents, Lipton made a surreptitious detour to Ceylon with little fanfare. Lipton arrived at a time when Ceylon was recovering from ‘Devastating Emily’ – the coffee rust fungus which destroyed the island’s thriving coffee plantations. Seated at the Grand Oriental Hotel in Colombo, Lipton discussed business prospects in Ceylon with his agent and decided to break his journey. Never one to procrastinate, Lipton took advantage of the plummeting plantation prices, inspected an estate, made an offer to its London owners and soon, was the owner of five plantations.

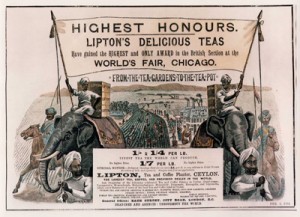

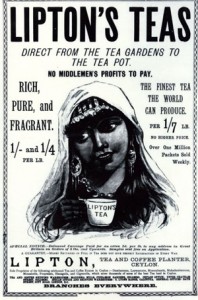

An entrepreneur at work: Lipton’s eye-catching posters to capture the market

To examine the Scottish tea baron’s empire, his rise in the grocery trade is essential reading. Thomas Lipton was every marketer’s dream. He had the kind of outlandish vision and creativity which most marketing professionals spend their lives trying to attain, and tempered it with philanthropy, business acumen and old fashioned hard work. After multiple odd jobs and a four year work stint in New York, he returned to Glasgow to help with his family grocery store. True to nature, his homecoming was a flamboyant one. He arrived in a horse cab with a rocking chair and sack of flour for his mother, strapped to its hood, and paid the driver to drive slowly through the neighbourhood, greeting old faces excitedly.

Restless to begin his own business and eager to test the learning gained from America, he opened his first grocery shop. He operated as its manager, errand boy, cashier, buyer and shop man and often slept on a makeshift bed behind the counter. There were two fundamental lessons from his grocery days which helped in marketing Ceylon tea – selling quality goods at lower prices by eliminating the middle man (he strived to eliminate “wherever possible, the middleman or intermediary profiteer between the producer and consumer”) and showmanship.

His marketing gimmicks included parading pigs with ribbons tied to their tails through the town bearing the signs “I’m going to Lipton’s. The best shop in town for Irish bacon!” – perhaps not the most sensitive of stunts but it caught people’s eyes. Along with its well-lit and colourful shop displays, Lipton expanded his chain of stores. He went on to print Lipton currency notes, imported the world’s largest cheese – embedding it with gold sovereigns (every single piece of cheese was sold to an excited crowd, in two hours) and used catchy advertising slogans and cartoons to garner attention.

His marketing gimmicks included parading pigs with ribbons tied to their tails through the town bearing the signs “I’m going to Lipton’s. The best shop in town for Irish bacon!” – perhaps not the most sensitive of stunts but it caught people’s eyes. Along with its well-lit and colourful shop displays, Lipton expanded his chain of stores. He went on to print Lipton currency notes, imported the world’s largest cheese – embedding it with gold sovereigns (every single piece of cheese was sold to an excited crowd, in two hours) and used catchy advertising slogans and cartoons to garner attention.

With the slogan “Direct from the tea garden to the teapot”, Thomas Lipton soon capitalized on the freshness of Ceylon tea, controlled the manufacturing process and maintained that consumers should insist on Orange Pekoe. The phrase “No Middlemen’s Profits to Pay” also became a selling point in Ceylon tea and Lipton went on to make tea – once a product for the rich – accessible to all by making it more affordable. It was also Lipton who popularised individual tea packets to guarantee freshness and tea bags– tea was mostly sold loosely from large tea chests and roughly packed in paper cones – and introduced cable operations to the tea factories.

The final product itself – from the taste, colour, intensity and fragrance – is intricately intertwined with the conditions it is grown in, making tea highly variable to weather and regions grown. A convoluted inheritance of its colonial past, Sri Lanka’s tea industry has been sculpted with increasing global competition, volatility in the industry and decline in key markets and is still very central to the country’s narrative and identity.

Even today, there are lingering vestiges of Lipton’s legacy. A visit to Sir Thomas Lipton’s Bungalow near Dambatenne Estate, Haputale offers views of verdant green and is surrounded by a sprawling, well-manicured lawn, providing a glimpse of why it was Lipton’s favourite resting place in Ceylon.

Located near the Dambatenne tea factory and at the top of the Poonagala Hill, Lipton’s Seat is said to be the highest point among the region’s tea estates and was where Sir Thomas Lipton would go to proudly survey his tea empire. With a panoramic view which rivals World’s End, visitors make the trek uphill before thick mists envelop the hills. These days, if you make your way to Lipton’s Seat, you’ll also find a statue of Sir Thomas Lipton at the top – an initiative taken by Lipton Ceylonta, to tap into its namesake’s heritage and relaunch and revive its tea brand. Hat on head and cuppa in hand, the moustached tea baron is perched on a seat surveying his tea legacy, a smile etched on his metal face.