Elections over, Sri Lankans should be optimistic now

When I say that “Sri Lanka is at the doorstep of take-off to economic prosperity”, many would raise eyebrows. Global economy is in a disarray, and the Sri Lankan economy is in a chaos; how can we say that we are now at the doorstep of take-off? That is exactly, my point: we never had such an opportunity throughout our post-independent history to ensure road to prosperity.

We should not, however, undermine the fact that we have a choice too, either to prosper or to perish. What I mean by this is that “there is no middle path now” unlike the one we had in history; in that “middle path” we often try to accommodate lukewarm policies, diluted with populist politics.

External Factors

External Factors

Let us first examine the global factor: The downturn of the global economy did not start with the US financial crisis. Rather, it was the bottom of the cycle. If we focus more on the bottom, we would miss the cycle where the recession began in the 1980s after the end of the postwar economic expansion in advanced countries. Why this point is important is because in recessions global capital is flowing out. The increase in capital flows from advanced countries makes the recession sharper than anticipated. Where is capital flowing into? The following points are some of the highlights regarding FDI flows in the world, according to the UNCTAD database:

1. Before 1987, world FDI flow was less than US$100 billion a year; until 1997, it was less than $200 billion a year; after 2006, it was around S$1,500 billion a year.

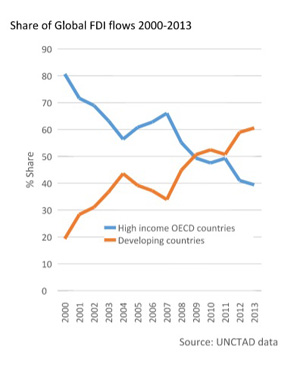

2. Earlier FDI flows were mostly within advanced countries, but gradually they diverted to developing countries, Before 2001, developing countries received only about 25 per cent of (or sometimes even less) global FDI inflows; this share exceeded 50 per cent by 2009, and 60 per cent by 2013.

3. Most of the FDI flows are coming to Asia in general, and to East and Southeast Asia in particular; in 2013 this region received $335 billion FDI – more than 10 times higher than what South Asia got.

The last point here raises another issue: Even if most of the global FDI flows are into Asia, the most attractive destination within Asia is the East and Southeast region. South Asia, in general, has not been an attractive FDI destination. But as economic and political atmosphere in East and Southeast Asia begins to change, a sizable share of global FDI flows into other regions would begin to grow too. The slump in the stock markets in China is a new factor that has been added to the changing economic atmosphere in the East. We should not ignore that the fast growth of stock markets in the East and Southeast region was at least partially due to the massive money growth in advanced countries – particularly USA, EU and Japan. After all, global FDI flows should still grow, even if East and Southeast Asia continues to remain as same as it used to be in the past.

Internal factors

Let us now look at the second part of the issue – domestic factor: Why do we think that Sri Lanka is ready to take off? I am not referring to the end of the 30-year long war. It was indeed a necessary condition, but not a sufficient condition; if it were, we would have seen some extraordinary economic trends over the past five years, including FDI inflows. I do not even think that the conflict was over (although the war was over), because we still have to embark upon a programme of national integration. The main point is that the Sri Lankan economy has now come to the end of the road in its lukewarm policy making: It requires a complete overhaul with a bold and purposive “reform” process. The term “reform” looks like a discarded word in the policy-making arena; but it is the one that Sri Lanka needed right now, if we choose to prosper. There are major areas where reforms need to be directed at; government finance, external finance, and business environment.

Government Finance: putting it under control

We begin with the government’s financial position. As recorded in the Central Bank’s Annual Report 2014 (pp. 143, 154), government’s tax revenue was Rs. 1050 billion and the repayment of government’s loan installment (debt service) was Rs. 1076 billion. If tax revenue is insufficient to pay the loan installment, then all other recurrent and capital expenditure of the government (reported in the budget) should come from further borrowings. For that matter, in fact, the government continued to borrow from both domestic and foreign sources in the last few months upto September 2015, too. Sri Lanka’s total outstanding government debt by the end of 2014 was more than 700 per cent of its tax revenue, which made Sri Lanka one of the highest-indebted countries in the world. And this does not include the loans of the government-owned enterprises.

The package of reforms concerning the government budget is clear: There is no room for playing with public money anymore. Wasteful and unproductive public expenditure has to be curtailed; public institutions and administration have to be efficient and demand-driven; public enterprises have to be on equal-footing with private enterprises; expenditure has to be frozen, and debt burden has to be reduced and be manageable. Of course, tax collection has to be fair and efficient too, by placing all individuals of the population in a fiscal database.

External Finance: Reflecting the productive strength

So far we have managed a fragile exchange rate which has always been under pressure. Weak external finances as reflected in our balance of payments (BOP) clearly show the fragility of our exchange rate. In the current account of BOP, it should be the export growth that reflects the country’s productive strength. But, according to the Annual Report 2014 (pp. 104) of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, our net exports (including services), show over $6 billion deficit in 2014, which is covered by over $7 billion worker remittance. In the financial account of BOP, foreign direct investment is less than $1 billion, but net debt liabilities over $1.8 billion; this debt is government debt, directly or indirectly, and the government has approached the limits of borrowings. Both characteristics in the current and capital accounts are not the signs of prosperity, but incapability and incompetence.

Sri Lanka had already approached the end of the tunnel in its external finance too: Most of the time in the past we could manage the exchange rate just for some external incidents. This year too, sharp decline in oil prices by more than two-thirds and India’s currency swap amounting to $1.5 billion so far helped the Central Bank to manage the exchange rate. Should we wait for the fortunes of another as such?

As long as our exchange rate does not reflect the international competitiveness of our productive strength, it will continue to remain fragile. The free float will not help either. Where is the problem? It is primarily the sluggish export growth, which of course is not the responsibility of the Central Bank. Export growth should replace worker remittances (in the current account), and FDI growth needs to replace foreign borrowings (in the financial account). Our export growth strategy is rusty now as we did not introduce reforms in that area after 1989. As far as the export growth is concerned, what is important is the productive capacity expansion, as outlined below.

Productive Capacity: Competitive improvement in business environment

Productive capacity determine sustainable economic growth and export growth. Productive capacity is determined by investment (both private and government, and both local and foreign), and in the long-run human resource development and technology improvement – two important areas where Sri Lanka has continued to make little investment.

Let me touch upon the investment episode. If Sri Lanka expects to sustain its economic growth rate around 10 per cent (annual average), which is indeed not a difficult task now, it should raise its investment ratio to around 40 per cent of GDP from its current level of less than 30 per cent.

The Government is not in a position to raise its investment now, as it has already reached the limits: Its investment remains closer to 7 per cent of GDP and in fact even this is also based entirely on borrowings. Therefore, it is the private sector which must raise investment to around 33 per cent of GDP from its current level of 23 per cent. The problem is, our domestic private sector and entrepreneur class is so tiny they have no capacity to make a massive leap forward as required.

There is, however, no shortage of investors and investment funds in the world, as we have seen through an exponential growth of FDI flows. If Sri Lanka could attract just 1 per cent of that, it would amount to $15 billion a year. If any country is looking forward to raise FDI inflows, there has been no better time than today, and Sri Lanka has all the qualifications to do so.

This is where the reforms are required to make Sri Lanka an internationally competitive business environment in the Asian region. Thus an establishment of an attractive business environment remain the fundamental issue, which would contribute to the improvement of both internal and external finance as well.