News

Fearless school head stood by his convictions at great risk

At the height of a ceasefire between the Tamil Tigers and the military, a school Principal in Jaffna organised a cricket match between his students and the Sri Lanka Army. He paid for it with his life.

Chelliah Edwin Anandarajan was riding his scooter to a friend’s house around 5 p.m. when the LTTE stopped him and shot him dead. It was June 25, 1985. His family was afraid to bring his body home. They sent an empty van ahead and smuggled his remains through byroads into the house.

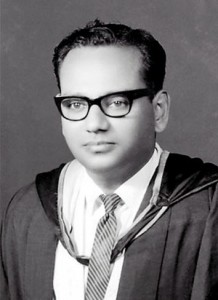

Anandarajan

The Tigers had come there with guns the previous night. Mr. Anandarajan and his wife, Padma, were out. So they delivered their sinister message to his brother and the help. Friends and relatives urged him to seek safe haven. He refused.

On Saturday, his family will commemorate Mr. Anandarajan’s life with a public lecture at the Peto Memorial Hall in St. John’s College, Jaffna—the school he served from 1976 until his death at the age of 53.

It is the first time in 30 years that the family has felt the conditions were right. The LTTE is no more and Sri Lanka is on the path to reconciliation.

Today, Padma lives in Toronto, Canada, where three of her children also reside. Another is in New Zealand while Dev, a pastor, has made Australia his home.

“My husband was killed because he stood for non-violent principles,” Padma told the Sunday Times, via Skype. “He did not allow anybody to come into school and interfere with administration. He was not afraid.”

Once, a militant group wanted to distribute pamphlets inside the school. Mr. Anandarajan stood in the way. He told them that he was in charge of St. John’s College and that he would quit if his orders were disobeyed. The resentment and anger over such defiance grew over time.

But cricket was the trigger that ended his life. “He believed in peacemaking,” Padma, now 83, narrated. There was a ceasefire between the Army and the terrorists.

Mr. Anandarajan organised a friendly cricket match between St. John’s and the Army. There was opposition; the Tigers did not want it.

Several matches were planned, pitting a combined schools team against the Army. Fear of the Tigers prompted the other schools to pull out. So Mr. Anandarajan fielded a St John’s team.

Only one match was played, after which the tournament was cancelled. But that single encounter was enough for the Tigers to shoot him dead.

“His killing came as a shock to me,” his son, Dev, said through e-mail. “When I first heard he was gunned down I thought the SL Army had done it as my father was also critical of the Government.”

The word ‘fear’ was not in his vocabulary, Dev said: “I’ve felt that he could have been cautious. It is no point in walking into a lion’s den. One knows the consequences.

Still, when one is committed to pursue the path of peace, ideological clashes with the enemies of peace, or those who refuse to see alternative ways and have chosen violence, lead to tragic consequences.

The only way out is through compromise or total surrender. My father would not compromise his convictions.”

Mr. Anandarajan lost his mother early in life and took on responsibilities at a young age. He attended St. John’s College (SJC) and completed his Bachelor of Science degree in India.

He joined the staff of his alma mater in 1955 but left it in the 1960s to complete a year-long postgraduate diploma in education at Peradeniya. In 1970, he was made co-Vice Principal of St. John’s College.

Five years later, he completed a diploma in education at Oxford, England. When he came back in 1976, he was made Principal of the school.

St John’s was an elite educational institution, far removed from the poorer rural schools of the day. Mr. Anandarajan’s answer was to offer scholarships to children of marginalised societies.

Admission was on merit, except for the offspring of teachers. The Principal had a quota. A few weeks before his death, a Jaffna newspaper carried an article about a widowed mother who sought entrance for her son to St John’s College.

The Principal told her that the conditions for admission included a fee or a donation as it was a private school. The mother could not afford it. But she returned the next day with the money.

He asked her how she got it. She had pawned her ‘thaali’ or wedding necklace. Mr. Anandarajan was disturbed. He drove the woman in his car to the pawning centre so she could redeem the necklace.

He then waived the admission fee and gave the boy a place at St. John’s College. “When institutions like SJC chose to remain private, they were forced to charge admission fees,” Dev said.

“The school gets no funding from the Church. It was much later that they agreed to Government assistance to pay salaries for approved teachers.”

“As a result, they lost the missionary vision of educating the underprivileged and marginalised,” he reflected. “But SJC always responded to crisis situations.

During the 1983 riots, when many fled to Jaffna, classes were expanded and the school took in nearly 400 students. In May 2009, it absorbed many children who were caught up in the war in the Wanni.”

Padma taught at Uduvil Girls’ College and Chundikuli Girls’ College, both in Jaffna. She retired from service at her husband’s death to be with her youngest son. At 16 years of age, he took his father’s death badly. “I wanted to be with him wherever he went,” she said. “He was the worst affected.”

“Each of his children coped in different ways,” said Dev. “Except for my sister, Sorna, the others were still students. Three of us were pursuing higher studies in India.

It was decided to move my youngest brother to a school in Bangalore so he could be close to me. I also took my mother to live with me in Bangalore till I finished my theological studies.”

Studies were an important element of any Jaffna family; something children were born and lived for. Today, the deterioration of standards is clear. The holistic education Mr. Anandarajan believed in is no more.

Dev believes the decline was caused my many factors including brain drain, lost skills, a survival instinct, lack of vision and resources, lack of creativity, initiative, imagination and poor leadership.

“My husband was a dreamer,” Padma said. “He wanted his students to have an all-round education with a development of their personalities.” It might be a while yet before Jaffna returns to its glorious past. But it is crucial to start somewhere.