Lankan food with a twist

For 25-year-old Andrew Speldewinde retirement has come a few decades early. Just a few months ago, Speldewinde began serving guests dinner in his family apartment in Colpetty. He named his ‘home chef venture’ Contemporary Ceylon.

While he also works as a business consultant for an IT services company, his new project is already earning him more money than he makes at his day job. That’s just the icing on the cake –Speldewinde still seems a little surprised that he is living a dream he thought was going to be a “retirement plan.”

Striking blend: Prawn vanilla curry

“I didn’t think we would get this much attention,” Speldewinde says as he lays the table for dinner. He’s pulling out napkin rings and cutlery and placing them on the counter. The wall behind him is covered in an enormous abstract canvas, but it is the view from the 23rd floor that draws the eye. From up here, the people on Galle Face are specks on the green, each wave a thin line of foam.

In the open kitchen, dinner is being prepared. A rack of lamb in a vacuum sealed, airtight bag has been lying in a water bath for 24 hours. Speldewinde is a sous-vide enthusiast for how the technique makes the meat incredibly tender and succulent.

He’ll pull the lamb out of its packing soon, and sear it on high heat. Once both sides are caramelised to his satisfaction, it will be time to rest the meat. There’s a Jaffna curry sauce and fresh mint to accompany the dish, but the real surprise is a light, translucent gel of ginger beer.

Speldewinde developed the dish himself –and it’s a reflection of the kind of food he would like to cook. Growing up he says he wasn’t a fan of Sri Lankan cuisine.

He comes from a family of foodies and always preferred the flavour palettes of Italian or Thai food. In fact he didn’t really develop an appreciation for the flavours of home until he moved to London to enrol in King’s College. “Being abroad helped me have that appreciation for my own heritage,” he says.

Even as his nostalgia for Sri Lankan food took root, he began to see how things could be done differently – for instance many local cooks overdid their vegetables and seafood. Stewing for a long time, beans would no longer have that crisp snap; prawns would go rubbery in the heat.

Speldewinde says he began exploring ways around that – a prawn curry for instance could be prepared with the essence of prawn heads, and allowed the cook to add the seafood at the last minute so it wasn’t overdone.

“The more I learned about food and the more I learned about the techniques that are out there, the more I thought about revitalising my own cuisine,” he says, naming as his inspiration Nordic chefs like Noma’s René Redzepi.

Speldewinde has no formal training, though he did manage to talk his way into being hired as a line chef for Ryu Gin in Hong Kong. “When I joined it had one Michelin star and had just received its second,” he says. Chef Sato put Speldewinde in charge of three dishes and “a lot of vegetable prep.”

He turned out custards, soups, gels and dumplings, and during service worked on cooking and plating select dishes. It wasn’t the job he had intended to look for but Speldewinde counts it as an invaluable experience.

Though he would eventually decide the hectic pace wasn’t for him, Speldewinde’s time abroad was decisive in shaping his palate. “My passion for food took a huge turn when I was in London because you are exposed to so many more things there,” he says.

Still, with only that one experience in the Hong Kong hospitality industry to call on, Speldewinde is remarkably confident. He knows he lacks the academic qualifications to pursue a career in the kitchen but says he still has “a lot of knowledge about food, how flavours pair together and what techniques to apply.” He keeps his notebooks filled with ideas for new dishes.

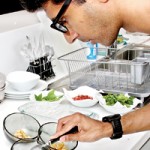

Personal touch: Andrew Speldewinde in his home kitchen. Pic by Indika Handuwala

His repertoire is currently small but impressive. There’s a tuna ceviche marinated in an oil flavoured with roasted onions and curry leaves that though served raw is designed to invoke the fried goodness of a theldala; he often follows with a dhal soup made with a base of Japanese dashi broth or a duck mulligatawny soup. For fans of prawn curry, he makes his with a strong hit of vanilla.

Speldewinde’s personal favourite though is his seeni sambol pork. It takes him three days to make. The sweet savoury sambol, so beloved by Sri Lankans everywhere, is served as both a gel and as dehydrated flakes atop a clean cut of pork.

He likes to top it with a sprinkling of onion flowers to reflect the flavours of the sambol. “For me it’s really about an emphasis on flavour,” he says, explaining that he uses“simple ingredients that all have a purpose on the plate – you don’t put anything on for show.”

For many guests, dessert seems to be the highlight of what is usually a five course repast. Today he’s serving a coconut and cardamom panna cotta with a coffee and jaggery crumb – but that’s because he’s expecting friends who he has bullied into trying out his new dish.

Otherwise every other caller seems to want the mousse and biscuit-crumb concoction he dubs Textures of Milo. “Everyone always goes crazy for the Milo dessert. A common thread is how it always reminds them of their childhoods.”

In August he served 50 people, in September, he’s likely to serve even more as his little kitchen’s reputation grows. As he strives to deliver a singular dining experience, Speldewinde is finding himself challenged and rewarded in equal measure.

Standing behind the stove, a few feet from the table, he can often hear his quests exclamations of pleasure – “The best part is when people appreciate the care and the thought that has gone into each dish,” he says.