Story of a ‘might-have- been’

The history of cinema is punctuated by a number of great ‘might-have-beens’: film projects with extraordinary artistic potential that unfortunately were never realised. Probably the best-known of these is Sergei Eisenstein’s Que Viva México! There are others just as tantalising.

Take The Alien, which, if it had been made (around 1967-8) would have had a profound impact on the genre, as did its contemporary, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

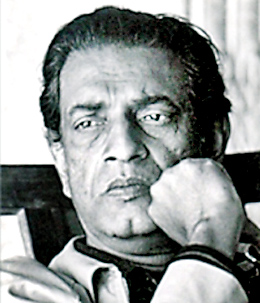

Satyajit Ray

Indeed The Alien would have thematically and philosophically upstaged Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). It might have made these blockbusters difficult to produce in their known form, due to plot similarities with The Alien: which is not coincidence but plagiarism according to many, in particular Satyajit Ray.

In addition, Ridley Scott’s namesake film and its sequels (with which Ray’s project should not be confused) would have had to undergo a title change.

The story of the failure of Ray’s project contains elements that could comprise the plot of a novel concerning a doomed Hollywood film production: machinations over the copyright ownership of the script, the director’s mistrust of the producer’s motives, contention over the casting, and a demonstration of the ruthless nature of the film industry in general and Hollywood in particular.

Embellishing the story are some remarkable vignettes redolent of the 1960s, such as Peter Sellers on the one hand performing his Inspector Clousseau routine over lunch with Ray in Paris, and on the other, learning to play the sitar from Ravi Shankar in Hollywood.

Or Ray, the refined Oriental artist and innocent abroad, confounded by the discovery of no less than six paintings by Augustus John in Jennifer Jones’ bathroom, and aghast at Mike Wilson’s unbridled excesses at the London Hilton.

The action constantly shifts from Calcutta, Ray’s native city, to Paris, London, New York, Hollywood, and somewhat surprisingly, Colombo. For Colombo was home to Michael J. Wilson and Arthur C. Clarke, both involved in the project to varying extents. Clarke was responsible for bringing Ray and Wilson together, and tried to keep the creative partnership afloat after affairs started to go disastrously wrong.

Wilson travelled with Ray to Europe and North America in search of project finance, assumed the position of producer, and managed to persuade Peter Sellers, Marlon Brando and James Coburn to express interest in the project. During the course of 1967, Wilson became first a firm friend and collaborator (apparent from Ray’s unpublished correspondence in my possession), but then a sworn enemy of the director.

Mike Wilson

There are references to The Alien in books and articles devoted to Ray and Peter Sellers, and there is an extensive article about the project by Ray himself. The first references and derogatory comments on Wilson are contained in Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray by Marie Seton (London: Dennis Dobson, 1971).

Then on 4 and 5 October 1980, Ray’s article titled “Ordeals of The Alien” was published in the Calcutta Statesman. In this article Ray places the blame on Wilson for the fact that the project never came to fruition, a charge vigorously refuted by Wilson in a rejoinder to the editor.

Unfortunately this letter was only published in part: the editor omitted all references to Ray’s earlier enthusiasm concerning Wilson.

It was at this point in time that Wilson (now Swami Siva Kalki and preoccupied with matters of a non-temporal nature) gave me his file on The Alien in the hope that I might one day provide an impartial and factual account of the project.

This file contains vital correspondence between Ray, Wilson and Clarke, generated between January 1967 and March 1981, as well as communication with prospective members of the cast, such as Peter Sellers and Marlon Brando, together with various press cuttings regarding the project. It’s an off-beat cinematic goldmine.

My first action was to offer access to the file to English film critic Alexander Walker to assist him in the research for his book Peter Sellers: The Authorised Biography (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981). This was the first instance that reference was made to Peter Sellers regarding his association with The Alien project.

Eight years later appeared The Chess Players and Other Screenplays by Satyajit Ray, edited by Andrew Robinson (London: Faber and Faber, 1989), and Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye authored by Robinson (London: Andre Deutsch, 1989).

The former publication includes the screenplay of The Alien together with the editor’s overview of the demise of the project, which is based on Ray’s article. Robinson was introduced to me by Arthur C. Clarke, and as Ray’s biographer has been intrigued by the correspondence.

Reference to The Alien is contained in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers by Roger Lewis (London: Century, 1994). In his book Lewis reproduces a lengthy letter sent to him by Ray in 1990.

Ray’s impression of the alien

This letter is a recollection of The Alien project with the emphasis on Peter Seller’s involvement – an episode that Ray admits is “twenty-five years old and a bit hazy in my mind”.

Locally, Swarna Mallawarachchi gave an interview in the Sunday Leader of October 2, 1994, with the emotive heading “Satyajit Ray and Lanka’s Shame”. Mallawarachchi recalled meeting Ray in 1987, and how he told her he “visited Sri Lanka many years ago, and vowed never to do so again due to a very bitter experience.

He had been cheated by a Sri Lankan (sic) in the matter of a script that would have been the first science-fiction film made in America (sic) if this incident had not occurred. Though he had been invited many times, staying true to his word, he never visited the country again.”

Certain incidents during The Alien project created in Ray a deep hostility towards Wilson. Every Sri Lankan Ray met had to hear his account of “being cheated in the matter of a script” and in the re-telling inaccuracies tended to creep in.

Take Mallawarachchi’s rendition, where Wilson becomes a Sri Lankan, the incidents took place in Colombo rather than Hollywood and London, and the location for the film is transferred from India to America.

What happened is that Ray had neglected to take the elementary precaution of copyrighting the script of The Alien in Calcutta. So before Wilson launched the script around Hollywood, he copyrighted it in both their names. Unfortunately, Wilson did not inform Ray of his action, and this lapse had serious consequences for their relationship.

Because it was an unmade film, the authors of the books earlier referred to only touch on the subject, although both Walker and Lewis advance some interesting theories as to why Sellers eventually withdrew from the project.

A more definitive account had therefore still to be written. This task I commenced in 1991, not knowing that fate would decree that both Ray and Wilson would depart before it was completed.

After Ray’s death in April 1992 I suspended work having compiled a 30,000 word manuscript; anxious it would be construed I was taking advantage of his demise to refute his accusations against Wilson (although he had had his say on the subject). Swami Siva Kalki passed away in February 1995.

Spurred to publish, I was advised some of my vital comments regarding Spielberg would attract the attention of his rapacious Hollywood lawyers. Deflated, I pushed The Wrecking: The Story of Satyajit Ray’s Ill-Fated Science-Fiction Film Project, The Alien) to the back of a drawer where it has remained.

Maddeningly, however, several similar assertions have been published in interviews, including a scorcher by Martin Scorsese, without recourse to legal action.

A year after Swami Siva Kalki’s death there appeared “Requiem for a Director” in The India Magazine (July 1996), another reason for me to attempt to publish the manuscript.

The article’s author, Siddhartha Deb, draws a parallel between the archival tragedy of Ray’s film negatives and The Alien fiasco. “I don’t think these events and motley cast of characters would have come as a surprise to Ray.

As his article ‘Ordeals of The Alien’ makes clear, he had first-hand experience of crooks who professed great admiration for him. In the story about Ray’s attempt to obtain financing from Hollywood for a science-fiction film called The Alien, the star part belongs to Mike Wilson.”

Why authors allow complete or incomplete manuscripts to languish (or destroy many of them as is the case with ‘our’ John Still) is a subject I don’t intend to analyse here (see my “When the Pen Falls”, The Sunday Times, April 26, 2015). So will it, won’t it, will it, won’t it ever have an ISBN number, to misquote the Mock Turtle? That I have written this introduction may be an encouraging sign.

| Ray’s village tale So what was the charming script that Ray wrote, with or without Wilson’s help? It is based on his short story “Bankubabur Bandhu” (“Banku Babu’s Friend”) which appeared in Sandesh, the Ray family magazine, in 1962. It concerns a small humanoid creature which lands its spaceship in a lotus pond in a remote Bengali village. In the script Ray describes the creature as “a cross between a gnome and a famished refugee child: large head, spindly limbs, a lean torso. Is it male or female? We don’t know. What its form basically conveys is a kind of ethereal innocence, and it is difficult to associate either great evil or great power with it; yet a feeling of eeriness is there because of the resemblance to a sickly human child.” Ray was a competent artist, having studied at Rabindranath Tagore’s school at Santineketan. He drew character sketches and costume designs to assist in the visualisation and planning of his films, and The Alien was no exception. The first drawings of Ray’s imagined humanoid, dating from December 1967, show the large domed head in detail. It has a narrow, pointed jaw, a small nose, sunken eye-sockets, and reptilian apertures as ears. Filled with child-like curiosity, the alien hops around the village examining amoebae, flowers and insects, and encounters a waif called Haba. The alien enters Haba’s subconscious; they become friends and play hide-and-seek in a dream-world of geometrical forms. The villagers awake next morning to discover that the paddy has ripened overnight. And Haba draws attention to the emergence of a golden spire from the waters of the pond. It is the beginning of much mischief-making by the alien, which sets villager against villager. The ‘miracle’ of the ripened paddy convinces the villagers that the structure in the pond is a submerged Hindu temple, and they commence to worship it. However a young journalist from Calcutta, Mohan, living in the village writing about development in rural India, cannot accept such an explanation. Neither can Joe Devlin (Marlon Brando/James Coburn), a no-nonsense American engineer from Montana, who is there to sink a number of tube-wells. Devlin’s employer Bajoria (Peter Sellers) is a wealthy and unprincipled industrialist of the Marwari community, renowned for its business acumen. (Many film producers in Bengal are Marwari.) As a rich man in a poor country Bajoria is anxious to create an image of himself as a philanthropist. When he sees the golden spire he realises it could enhance his reputation: salvage it, restore the temple in his name, and turn it into “the greatest place of pilgrimage in India”. Bajoria persuades Devlin to pump out the water from the pond. Later, after a session of whisky-drinking and hashish-smoking, Devlin bumps into the alien but is too stoned to comprehend his encounter. The alien has been up to other pranks: making a mango-tree owned by the meanest villager bear fruit out of season, and causing a corpse to open its eyes on the funeral pyre. These events convince the villagers they have been cursed, and that the object in the pond is responsible. The next morning Devlin and Bajoria, accompanied by Mohan and a salvage crew, converge on the pond. Devlin swims out to the spaceship, which suddenly begins to throb, hum and pulsate with light. After he beats a hasty retreat the spaceship takes off, with the alien, his friend Haba, and various specimens of earthly flora and fauna on board. Mohan realises he has a story to write. Bajoria, overcome by the experience, takes comfort in piety. And Devlin is revered by the villagers for having saved them from the alien’s magic . . . |