Lankan doc who battled on

He fled the fighting in Sri Lanka only to get caught up in Liberia’s war. In July, the West African nation awarded consultant dental surgeon Markandu Kanagasabai its top civilian award for facing down conflict and a deadly Ebola outbreak in the line of duty.

Dr. Kanagasabai in Colombo. Pic by Athula Devapriya

Dr. Kanagasabai, 74, is the first Sri Lankan to receive the distinction of the Grand Commander in the Order of the Star of Africa. And he is only the second foreign doctor to do so in Liberia. He emigrated nearly four decades ago with a young family.

They have endured internal displacement and even once lived as refugees. Their old photographs were lost in multiple lootings.

Liberia has a tumultuous political history. GlobalSecurity.org calls the country’s civil war, which lasted from 1989 to 1996, “one of Africa’s bloodiest”. Hundreds of thousands were killed or routinely displaced as a result of fighting between competing factions.

In 1980, Liberian President William R. Tolbert, Jr, was assassinated in a military coup. Dr. Kanagasabai was vacationing in Sri Lanka. He had to choose whether to stay on or return to Liberia. “We heard things were getting better so we came back,” he said, via Skype from the capital Monrovia.

The civil war started in earnest in 1990. Expatriates were evacuating in droves. The Kanagasabai family was also advised to leave. But their air tickets were still being processed and the airport was suddenly shut down. “We were forced to stay behind,” the doctor said. “We could not leave in 1990. I continued to work through it.”

That year, they suffered their first displacement. They stayed with a friend in a different town. Their own house was looted and they lost many of their belongings. But the most dramatic moment came in 1994, with another wave of violence.

They were forced into a camp for 23 days, held hostage by a warring faction called the National Patriotic Front of Liberia. They were rescued by helicopter after which a friend gave them shelter. Once again, their house was ransacked.

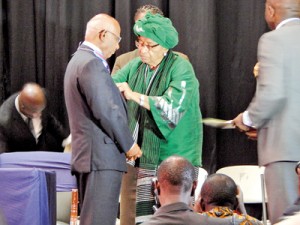

Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf pinning the medal on Dr. Kanagasabai

There was a shorter spell of displacement in 1994. Two years later, a militant group came to the Kanagasabai residence one evening and ordered them out.

“We were escorted to the US embassy where many other foreigners, including Lebanese and Indians, were gathered,” Dr. Kanagasabai recollected. “They took us to neighbouring Senegal in a helicopter. We were refugees.”

In Northern Sri Lanka, too, there was turmoil. “I asked myself if we had jumped from the frying pan into the fire,” he said. “We came here in 1978 and became internally displaced, then refugees, with nothing in hand.”

They tried to make sense of their situation. To end further disruptions to the schooling of their three children, Dr. and Mrs Kanagasabai admitted them to educational institutions in Colombo. But the couple returned to Liberia. One reason was financial.

“Between 1990 and 1994, my salary was not paid fully,” Dr. Kanagasabai explained. “The Government owed me a lot of money. If I stayed in Sri Lanka, I would not have got my dues. So I had to come back. It was not a small sum.” After the hospitals opened, he secured a position in a teaching hospital.

Today, he heads the ‘Oral Health Outreach Programme’ of Liberia’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. After the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Liberia free of Ebola, Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf wanted to honour doctors who had been at the frontline of the battle against the disease.

Dr. Kanagasabai was one of them. He received his award from the President. He was also recognized for 37 years of service to the country.

Dr. Kanagasabai was born January 1941 in Jaffna. He has four sisters and five brothers. His father owned paddy lands in Jaffna and Kilinochchi and also ran a transport business.

They lived at Stanley Road. He attended Jaffna Central College until 1962, when he passed his University of London pre-medical examination.

“Those days, everyone from Jaffna aspired to go to University and to get a good job,” he reminisced. “That was our investment. I know that from the time I went to school that I wanted to become a medical doctor. I was working towards that.”

Sports played an important role in his life. The young Markandu was a boxer, pole-vaulter and distance runner. He gained admission to the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya. “We had a good time there,” he reflected.

“The Peradeniya campus was huge, with more than 5000 students from all parts of the country. We had a good relationship without racial or communal differences, unlike nowadays. For most of my time there, my roommates were Sinhalese boys.”

Dr. Kanagasabai left university in 1969. He then completed graduate training at the Dental Institute in Colombo. He was posted to the Bandarawela District Hospital and the Diyatalawa Base Hospital from 1971 to 1973.

The last station he served was the Matale Base Hospital. He also married Rajeswary who, to this day, takes care of the homefront. She is now 68 years old.

There were ominous happenings around the country. In 1971, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) insurgency manifested itself. It was quickly, and brutally, brought under control.

There was then an exodus of planters—British, Scottish, Tamil and Sinhalese—to Australia as the Government started to take over the plantations. They did not wish to work under the State.

The United National Party swept to power in 1977. The general election was followed by attacks on Tamils. “At the time, we had two children who were aged two-and-a-half and one year,” Dr. Kanagasabai said.

“We had to run for our lives. During the weekend curfew, Dr. Palipane took us to his house for safety.” As with many other Tamils, the lives of Dr. Kanagasabai’s family were saved by Sinhalese who abhorred the violence.

“We resumed work,” the doctor continued. “There were night curfews. I worked mornings. After that we decided we must go abroad. After nine years of service, we thought of leaving the country.

A classmate and friend in Liberia sponsored me and in April 1978 I left Sri Lanka and came to this country to work for the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare.”

The facilities were good: a free house, car, driver, gasoline and maintenance. Their family grew to five with the addition of another son. The way of life was American.

Liberia was part of the American Colonisation Society and had gained independence in July 1847. Despite living there for 37 years, Dr. Kanagasabai retained his Sri Lankan passport.

One of the most serious crises faced by the country was the Ebola outbreak. “We lost about four or five Liberian colleagues,” the doctor said, soberly. He was working at the hospital whereas Ebola patients were handled at Ebola Treatment Units (ETU) set up around the country.

“Still, during this time, every patient was considered to be an Ebola suspect,” Dr. Kanagasabai said. “We had to wear personal protection equipment that covered us from head to toe. We handled patients with gloves. We were forced to take special measures.”

Hospitals stopped non-essential procedures, like elective surgery. They left room only for emergencies such as in the maternity or paediatric wards. It was not an easy time. The families of doctors and other health workers were worried about them. But health workers battled on.

“When you go to war,” mused Dr. Kanagasabai, “you have to fight. You can’t run away. We are medical people. We can’t run away from diseases.”