An autobiography as fascinating as his fiction

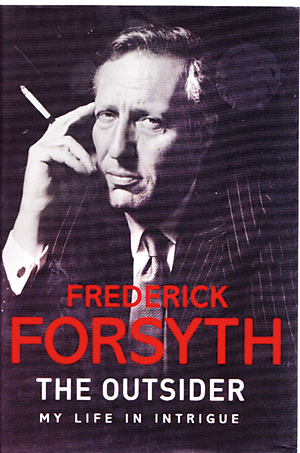

View(s):British author Frederick Forsyth’s admittedly last book at age-76 is his fascinating autobiography, The Outsider – My Life in Intrigue, which is as absorbing as every one of his 17-books on fiction, apart from two non-fiction tomes, The Biafra Story and Emeka.

In 60-short chapters covering 368-pages, Forsyth reveals the dynamic and dangerous life he has led over the years.

His adventurous life begins with his early-teen obsession to join the RAF and fly airplanes – starting his dream and ending it with the reality of flying a Supermarine Spitfire – and also ejecting from a parachute.

The latter half of the 20th century sparked off the spy genre with Len Deighton’s Harry Palmer, Ian Fleming’s James Bond, John le Carre’s George Smiley in especially the omnibus The Quest for Karla, not forgetting Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, and Frederick Forsyth’s stream of heroes, especially Sam McCready’s heroic feats in The Deceiver.

In a way, as the only child, Forsyth was lucky to have loving parents who conscientiously cared for his future. His dad’s discreet decision in sending his boy to France, Germany and Spain, exposing him to the mastery of the respective languages including Russian, served Forsyth well in the years ahead as a journalist and a spy.

Apart from being bestowed with a CBE by Queen Elizabeth-II for charity work, he well deserves a knighthood or even a better gong, for his high risk contribution to SIS as well as for his splendid literary works. Sometime in 1973, in a somewhat dangerous spy mission, he smuggled a pack of papers into the heart of East Germany outside Dresden, hidden craftily amidst the crevice of the battery of his Triumph Vitesse.

He was tasked to exchange the pack for a similar one from a Russian colonel working for SIS, and he courageously brought it over.

| Book Facts The Outsider – My Life In Intrigue by Frederick Forsyth. Bantam Press, Sep-2015. |

A high risk venture which, if detected by the Stasi, would have cost him his life, and deprived readers of the joy of reading such a remarkable series of his super thrillers.

During his undercover service, in the fashion of James Bond and in contrast to Le Carre’s dour portrayal of the ideal spy, Forsyth enjoyed his share of conquests in the ladies department, especially with one who “…was gorgeous, a twenty-one-year-old who could have stopped traffic on the highway,” who surprised him when she revealed herself to him in bed be from the StB!

Forsyth deals extensively of his exposure in the mid 1960’s Nigeria-Biafra war, in which over a million children died of malnutrition.

His stance against Britain’s support for the Nigerian government of Col. Yakubu Gowon, while he was supportive of the Oxford graduate and military governor of Iboland, Col. Emeka Ojukwu’s Biafra, is poignant if not shocking.

Forsyth’s stints with the Daily Express and Reuters which he thoroughly enjoyed and the BBC’s skewed policy which he apparently disliked, and the overseas postings, stood him in good stead in his future years as an author.

His first three books on fiction – The Day of the Jackal, The Odessa File and The Dogs of War – catapulted him into the global best-seller bracket.

The rejection of the Jackal manuscript, which he typed out in six weeks in Jan-Feb-1970, by three publishers was rather disturbing.

However, the editorial director of Hutchinson, Harold Harris, gave him a break of a three-novel contract, all of which subsequently hit the high mark.

Movie Director Fred Zinnemann’s pick of Edward Fox to play the Jackal was spot on, with the movie hitting the box-office.

The Odessa File sparked the desperate flight of the key Nazi fugitive, Eduard Roschmann, from Argentina to Paraguay, dying midway of a heart-attack. White mercenaries reportedly carried a copy of The Dogs of War on their deadly missions.

Like Ian Fleming, Forsyth travelled extensively to various points in the globe prior to commencing on writing a book, thereby giving it that touch of authenticity to the satisfaction of the reader.

As much as Fleming was sponsored by The Sunday Times on a worldwide tour in 1959-60 inspiring him to write Thrilling Cities, Forsyth enjoyed publisher Hutchinson’s generosity in travelling to a series of cities around the globe to accomplish his contract.

Forsyth reveals his right royal swindle in 1993 by a con-artist whom he trusted to handle his investment portfolios, reducing him almost to penury, where he eventually owed a million pounds sterling!

The culprit eventually escaped with a mere 180-hours’ community service.

That did not deter Forsyth. He embarked indefatigably upon writing a series of novels, recovering his losses and emerged with great success. He stated: “The Biafran affair had deprived me of any faith or trust in the senior mandarins of the Civil Service. The trial of 1993 did the same for my belief in the legal systemand the judiciary.”

Forsyth has this knack of telling a story by keeping the reader plastered to his opus, with a swell of accurate technical details, educating the reader continually on a specific subject or two.

It was similar in style to Fleming, who served in Naval Intelligence as a commander in WW2, in his 14 James Bond thrillers.

All in all, Forsyth has given us readers such splendid hours of delightful reading pleasure, which is far beyond requital.