There’s only one word for him, multi-faceted

A rich and vivid tapestry enhanced with diverse patterns emerging and merging, with a single golden thread running through it.

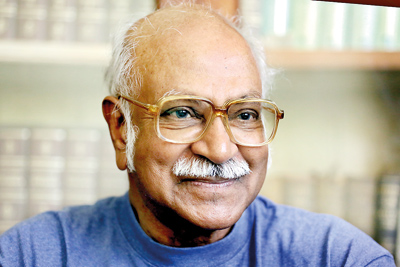

Man of eminence: Dr. Malik Fernando. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

In a palatial home exuding old-world charm down Barnes Place in Colombo 7, each and every pattern has been designated its very own corner with only one conspicuously absent.

The missing piece to all the clues of the life of this eminent personality is the tool of trade of a doctor, the stethoscope.

Our lengthy and interesting ‘chat’ with Dr. Malik Fernando begins on the ground floor of his home, continues in his book-lined study with much clutter to an observer but some “order amidst the madness” to him and concludes on the ground floor peering at his life’s collections over the years in this cupboard or that.

Truly a multi-faceted persona!

Tall and suave, he is as confident and comfortable on numerous, high-level medical committees as he is in his wet shorts diving off the coast of Sri Lanka or ambling along the white sands picking up shells.

His ‘collections’ which no one else wanted

The easy way out to write about Dr. Malik, I decide, would be to start at the beginning. When asked about his birthday, he laughingly says that he doesn’t observe that, only the anniversary of his retirement, the last one being “R-17”.

This 77-year-old comes from eminent stock. His father, Dr. Cyril, was the respected Senior Physician at the General Hospital, Colombo, and his mother, Dorothy, though a housewife, was a lover of nature, a legacy she has passed down to Dr. Malik.

He is an “old Bridgeteen”, having begun his schooling in the Montessori there, and then moving to St. Joseph’s College, Maradana, where he was “pretty average”.

The only sport he engaged in was swimming, being part of the under-16 team. But that did not last long, for young Malik was lured by underwater swimming, a “major pre-occupation since my middle-teens”.

Underwater swimming fascinated him and buying a pair of goggles, the long leisure evenings of boyhood he spent in the sea off Colpetty.

“It was the only thing at which I was better than most others,” he says, an interest which has endured.

Cycling was another interest though his friends never joined him, with Malik riding his bicycle to school and back and once indulging in a tour of Galle over a weekend and also in the United Kingdom (UK) when he was a medical student at the University of Bristol.

Another major fascination was the dissection of animals, like frogs which small boys love to catch, to study their anatomy, which stood him in good stead as a medico.

As our conversation veers to academic achievement, he recalls how he failed Sinhala at the Senior School Certificate (SSC) examination, not just once but four times in a row.

To get into a British University to study medicine, following in his father’s footsteps and an assurance by Dad before he died that there was money if he ever wished to go to the UK for higher studies, he had to have a pass in a second language.

All set for a dive at Hikkaduwa

A more recent achievement, however, is gaining adequate fluency in Sinhala to deliver lectures on marine biodiversity and also cycling.

According to Dr. Malik the moral of his brush with Sinhala is that somebody failing at a young age is not an indication of low intellect or ability. One can master many things with maturity, he says, tapping at the watch on his wrist.

It was a watch costing “quite a big sum” in a showroom window he had looked at longingly but only bought soon after delivering a lecture in Sinhala on marine invertebrates to the Young Biology Association of the Sri Jayewardenepura University.

“The half-hour talk was very stressful because of the language,” says Dr. Malik, adding that fortunately friend Arjan Rajasuriya was on hand to help him whenever he got stuck for words.

“When I completed the lecture successfully, I went straight to Fort and bought myself the watch.”

Harking back to why he chose “unheard of” Bristol University for his medical training, or rather the other way round, he says that those were the days when King’s College and Sheffield and Birmingham Universities were much sought after.

He tried but failed to secure placement in them. Around the same time, Bristol’s Vice Chancellor Prof. Bruce Perry was in town examining for the local MD, along with Prof. C.C. de Silva, who was one of Malik’s family doctors.

Links were established and when Malik met Prof. Perry at the Mount Lavinia Hotel he suggested that he matriculate for which a second language was also necessary.

He then resurrected his study of Latin, abandoned at 13. With Malik having to sit the London Advanced Level, it was to legendary educationist Fr. Peter Pillai who was then Rector of St. Joseph’s that he and his mother went to.

When Fr. Peter Pillai suggested that he leave college and join Aquinas University, Malik in turn requested a year more at college to do private study. Knowing Malik’s lethargy towards studying, the Rector had agreed with much reluctance.

“For the first time in my life I started studying,” he says, giving his rigorous routine – cycling early morning for Latin tutoring to Wellawatte, followed by school to master Physics, Chemistry, Zoology and Botany, poring over his Latin homework during lunch and then cycling back for the second session of Latin.

The clincher for all the hard work came when he scored four straight As at the London ALs and a credit in Latin at the OLs.

Twenty-one years plus a day old, he set sail for UK by himself in September 1959, cut off from family and friends for a decade, with only one visit by his mother and sisters in-between.

Those were the yester-years with no mobile phone and e-mails and airmail letters taking as long as a week or two weeks. To make overseas calls, which would be rare, he needed a pile of coins.

“Both university and hospital life thereafter was great,” says Malik, pointing out how in hospital the hierarchy was clear but in the evening at a pub that had a skittle alley (like bowling but with nine pins), senior doctors, nurses, radiology people and orderlies were on first-name basis, unlike in Sri Lanka where “thathvaya” (status) is very important.

For four years after Medical School, Malik worked towards becoming a surgeon taking six months off to study for the Primary Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) but it was a “gorgeous summer” and the sea beckoned.

“I spent most of my time diving and failed all four subjects,” he says, without the least embarrassment. He had, however, advanced to scuba diving and had a few girlfriends too.

Back in Sri Lanka, his mother launched a search for a bride for him, but the prospective fathers-in-law vetoed him, with some saying that he must have been with girls during his 10-year stint abroad, others wanting him to give up his diving or keeping snakes as pets, and one even wanting a letter from a priest vouching to his character which he would never have been able to get.

Yes, young and handsome Dr. Malik did fall in love, “there was one”, he says, but he had to make a choice – giving up his independent, outdoor, exciting life that he relished for domesticity.

The rest is history. Dr. Malik Fernando has not only dabbled in many things but also excelled at them, while working for just two weeks at The Central, then owned by Dr. Justin Fernando, a friend of his father’s, and leaving with the distinct feeling that he was “unsuited for work in Sri Lanka”.

It was then that he went back to medical school, following ‘greats’ such as Surgeon Dr. P.R. Anthonis, Physician Dr. Oliver Medonza and Paediatrician Dr. Stella de Silva for six months on their rounds and clinics both at the General Hospital and the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children, learning the local system, prevalent diseases and terminology, colloquial and slang.

This enabled Dr. Malik to get himself a job at the Municipal Dispensary of the Colombo Municipal Council as a relief medical officer, rotating at all 20 or more dispensaries in the seamy underbelly of the capital city.

It was a new experience for him, with conditions and attitudes being different and also making him learn a smattering of Tamil as his patients were a fine mix.

Job permanency was an impossibility without political sponsorship and his next and final job was at the Petroleum Corporation where “I spent the rest of my working life with no great money but adequate free time for the outdoors and diving”.

Acknowledging that “life has been rather lazy and laidback”, he says how 17 years ago he retired at the age of 60, refusing to work as a contract employee and “glad I made that choice”.

Service has also been an underlying part of his life, with Dr. Malik being the Honorary Physician to the Mallika Nivasa Samithiya and its home down Vajira Road for 21 long years……“a very rewarding experience as the old people needed someone to talk to, hold their hands and pat their heads, not so much whether they were being given beheth or not”.

Philosophical he becomes as he postulates how as doctors, “we have to stop people from dying but that can be carried too far. My philosophy is to keep old people comfortable and let them die in dignity when the time comes”.

Citing an example of an 80-year-old who is bed-bound, incontinent both at the front and back, he asks whether we should resuscitate such a person. His logic is: “We all have to die sometime or another.”

In his personal life, he was the beloved son who accompanied Mummy on her nature sojourns, looking for wild orchids, becoming an expert on very small specimens after putting them under a microscope and dissecting them, taking in the beauty of butterflies and studying dragonflies.

Extending his passion to encircle others, Dr. Malik helped set up the Recreational Diving Club in 1986, starting at various swimming pools and finally finding a home at the Sinhalese Sports Club (SSC) to conduct weekly diving training as well as scuba diving and for a little time even skin diving.

Numerous and diverse are the committees he has been and still is on, reflecting his wide and varied interests.

Rearing many animals in the 1970s and ’80s of whom nothing much was known because books on them were scarce, it was by observation that he learnt about them.

Snakes became one of the species, after his brother-in-law Dr. Upali Walgama brought one in a bottle having found it slithering around in his hospital quarters.

‘Sydney’ whom Dr. Malik took to the Zoo and was identified as a non-poisonous Mudu Karawala would become famous, travelling in a bag in his pocket, escaping many a time and resulting in massive snake-hunts.

His menagerie expanded later to harbour, a Kunu Karawala, a Russell’s viper, a cobra, a rat snake, a sea snake, a terrapin and even a baby crocodile. Of course, he never dared carry the poisonous ones in his pocket, otherwise he would not have lived to tell the tale.

All these led to Dr. Malik being sought after to be on committees such as the Snake-bite Committee of the Sri Lanka Medical Association (SLMA), the latter of which he headed as President in 1992; writing a chapter along with Dr. Walter Gooneratne on ‘Sea-snake envenoming’ for the landmark 1983 SLMA publication on ‘Medically important snakes and snake-bites in Sri Lanka’; SLMA Ethics Committee and Ethics Review Committee which he got onto “by accident”; National Species Conservation Action Committee through which he was able to include a checklist of species not discussed adequately including those in the marine environment; and Cycling Federation of Sri Lanka, to name some.

Over the years, his priorities have changed. Having a large collection of sea-shells picked up over 40 years, he is now preparing to write a book on ‘The Aquatic-Shelled Molluscs (Marine & Brackish) of Sri Lanka’, having edited many other publications on other subjects.

This is while he is also trying to compile a list of all the bric-a-brac that is spread across his home: The ‘rubbish’ from the bottom of the Galle harbour such as bottle fragments, clay pipes, plates and other ceramic pieces that he picked up while diving which nobody was interested in.

Making a presentation at the 4th Archaeological Congress along with Somasiri Devendra and Gihan Jayatilaka, he had brought to the notice of the scientific community the archaeological value of Galle harbour, which led to the setting up of the Maritime Archaeology Unit there.

All this and more Dr. Malik is able to do as he is not tied down by family. This vacuum is filled by the children and grandchildren of his home-helps past and present.

“They come for a short while and go away, after being treated to pizzas and burgers. The whole house buzzes the week of Christmas, as they put up the Christmas tree and decorate the place,” he smiles .

There is also no loneliness as his nephew lives next door and even though his two nieces are abroad; ‘Whatsapp’ keeps him linked, particularly to the one in South Africa.

Meanwhile, Dr. Malik has made his wishes very clear – “If I get ill, no heroic means should be resorted to keep me going. I don’t want to linger, when I am too old do things for myself.” Ever the voice of reason!