Sunday Times 2

A lost generation of Tamil youth

View(s):Dr. Daya Somasundaram, senior professor of psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, in this two-part article based on the Anandarajan Memorial Lecture he delivered earlier this month at St. John’s College Jaffna, analyses the impact of post-war trauma on the Tamil youth in the North, present psychosocial context and issues relating to education and globalisation.

War and natural disasters cause major consequences not only in youth but also in their families and society which we have described as collective trauma.

Where have all the flowers gone?

Gone for young soldiers everyone,

Where have all the young soldiers gone?

Gone to graveyards, everyone,

Where have all the graveyards gone?

Gone to flowers, everyone.

Oh, when will we ever learn?

Oh, when will we ever learn?

-Excerpted from Peter

We have lost too many of our youth, the blossoming flowers of our community, in the civil war. Loss came in the form of death and injury crippling them for life. The ones who survived continue to exist with physical and mental scars.

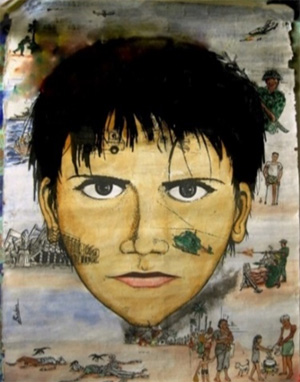

While the State terror and violence, military atrocities, detention and torture of youth and general discrimination against Tamils, particularly in university admissions pushed youth and students to join militant movements; the propaganda of the militants and other social leaders to arouse feelings of Tamil identity, motherland (Eelam), soil (mann) and blood (raththam); appeal to heroism (veeram), commitment (arpanippu), sacrifice (thiaham), a martyr cult, and adventure pulled youth into becoming child soldiers (Fig. 1).

Although leaders like Anandarajan resisted and eventually paid with his life, militants had a fairly free run of schools and other public places to carry out their meetings and videos to recruit students. Entire batches of students joined overnight or ran away from home, leaving a note in the sugar bottle for their mother. They were lured by the pied piper to their doom, to become cannon fodder on frontlines across the northeast.

Another section of youth migrated or fled to escape death, conscription or detention and possible torture.

Their desperate journeys took them across the Palk Strait to India, continents and seas in rickety, sinking boats; through freezing forests in Northern Europe, jails in South East Asia, Africa and Latin America and international borders, hiding as human cargo in containers and undercarriages of trucks, seeking refuge and asylum. The result is a world-wide diaspora of Tamil youth, some discontented with homesickness and acculturation stress, others doing well in their host countries.

Fig. 3 The path that resent youth have travelled through

The surviving, present day youth in Northern Sri Lanka face a grim future. There is a popular caricature of male youth, particularly among critical elders, that they hang around street corners, smoking, drinking and harassing females (Fig. 2).

They are wasteful of money and do not become involved in work or other constructive pursuits but spend their time on motorcycles and other consumer pursuits. A Northern judge has recently ordered police to arrest all ‘rowdy gangs’ hanging around street corners and put them behind bars following an increase in violence and other antisocial activities.

Collective trauma

Young people who experience massive trauma (Fig. 3) develop loss of concentration, memory impairment, hostility, loss of motivation, loss of efficacy in work, fear, anxiety, depression, relationship issues, and an increased tendency to become addicted to drugs and alcohol. War and natural disasters cause major consequences not only in youth but also in their families and society which we have described as collective trauma.

Traumatic events that their parents and society experienced at that time can be transmitted to children epigenetically, or through parent-child interactions, family dynamics, sociocultural perpetuation of a persecuted, ethnic identity based on selective, communal memories; and through narratives, songs, drama, language, political ideologies and institutional structures.

For example, the burning of Jaffna Public Library which contained invaluable manuscripts, books and other resources has been described as an act of ‘cultural genocide’ causing a permanent impact on the collective conscience influencing future generations.

The culture of impunity for such acts, lack of social justice and historic victimhood have created a ‘learned helplessness’, feeling hopelessness and anomie that makes youth flee their homeland, seeking haven and opportunity in foreign shores or commit suicide. Their children, too, grow up with hatred in their hearts and ‘chosen traumas’ in their minds.

Present psychosocial context

The periods of adolescence and youth have no clear-cut boundaries, tending to last much longer, into the later 20s in traditional societies like the Tamils, sometimes dependencies on parents, involvement with family and extended family, the adolescent behaviour patterns and role can last even into marriage and beyond. Adolescence and youth are critical periods of transition where the body goes through biological changes. It can be tumultuous period of tremendous upsurge in energy levels, behavioural changes, identity confusion and personality formation, rebellion, experimentation, risk taking, peer influence, independence, impulsiveness, adventure, sexuality and creativity.

Children have to grow up facing considerable abuse and violence within the family and even at school (see Table 1). Corporal punishment is widespread in schools. Many students are scarred for life and develop aversion to education from the punishing atmosphere in schools and home.

Fig. 2 'Rowdies'

Suicide rates have increased dramatically after the war. Sociologist, Durkheim, has shown there is drop in suicide rates during war due to increasing social cohesion but an increase after the war, due to various social factors described here like tearing of social fabric, collective trauma, anomie and hopelessness about the present and future. Psychoanalysts say that the drop during war is the opportunity to externalise aggression against a common enemy, while after the war, aggression gets turned inward due to a myriad of problems within the family and community.

Please turn to Page 12

Women in post war North and East have unique set of challenges. Young women shoulder the burden of looking after the family and earning an income often time alone due to death, disappearance, handicap or abandonment of the male in the family. Thus, there was increased demands and stress on females, some of who developed psychosocial problems like increased somatisation and other minor mental health disorders. In the post-war context, the shift in the gender power balance in a traditional patriarchal society, has made males resentful and more aggressive at home and outside. For instance women go for well-paid jobs at the Army-run CSD farms, then face problems at home with alcohol husbands and uncared for children. Others were lured to join the army with lucrative salaries and benefits but developed hysteria later on due to being unable to cope with military culture.

Alcohol consumption by males has increased dramatically after the war. Alcohol has been introduced even among school students, for example, by military alcohol mobile units in the Vanni. When considering psychosocial problems in the community, alcohol had a cross-cutting affect, being closely associated with domestic violence, crime, road traffic accidents, suicide and attempted suicide.

A crippling brain drain took place in the North and East during the conflict. Intellectuals and community leaders who courageously stood up for morals and principles were either intimidated into leaving or killed or made to fall silent. Youth were exposed to the culture of branding and labelling people with dissenting opinions as traitors both by the State and the militant groups. This self-destructive practice had left our community with a lack of vibrant leadership and youth without role models.

Education

Education is vital in moulding socially and culturally responsible citizens by influencing their thinking, changing their life styles and providing them with jobs. Unfortunately, our educational system is in a crisis. The Northern Education System Review (NESR) recommends one teacher for 20 students in primary divisions, and one teacher per 35 students in higher classes. However, in reality, especially in Vanni, the ratio can be anything between 100-400 students per teacher. Schools in rural areas are sometimes closed because teachers are not willing to work in remote villages where the facilities are fewer and travel related difficulties.

Education in Sri Lanka revolves around exams and grading. From the age of 10 where a child is pushed in to obtaining high scores for scholarship exams to ‘O’ levels and then ‘A’ levels, exam results have become the main measure for assessing the ability and standards of teachers, schools and educational zones. Furthermore the exam results are perceived as determining the social prestige and dignity of parents, and the self-esteem of children. In this keen competition for social standing, childhood is sacrificed for examination success without extracurricular activities including arts, sports, play; and religious and cultural practices. Children have to wake up very early and attend private classes in the early mornings and late evenings in addition to going to school. They are also beaten amply, and given physical punishments as well as made to undergo mental agony.

If we look at the exam results, 70% were unsuccessful in grade 5 annually and 50% failed the ordinary level (O/L) examination. In those who sit for the A/L examination, only 15% enter the universities. Is it the aim of the educational system to defeat most of its students? Is it a useful educational system if its main focus is only on exams? What will be the future of failures?

The university system that was doing reasonably well up to the early 80s have deteriorated drastically due to the general chaos of the war, poor resources and support from the state, loss of able academics, researchers and teachers with the general brain drain, and breakup of the university atmosphere of learning, development of character, artistic creation, discussion and activities. The time when lecturers like Rajani Thiranagama who interact with students to encourage widening of their consciousness and social concerns, develop their personalities and encourage a culture of lifelong learning are no more. Instead, we are left with a glorified tutory system that focuses on outdated notes and make or break examinations that do not prepare the students for the future or world outside.

Globalisation

War isolated youth in the North and East through blockades and travel restrictions. Post-war had seen an influx of financial companies readily lending credit, modern goods such as electronic equipment and tourism.

The financial companies and lending institutions that freely set up shop in every street corner after the end of the war, like the carpetbaggers after the civil war in the US, came in to clean up on the remittances and whatever meagre savings people were left with. State policies on development including infrastructure and facilities such as roads, electronic communication networks, trading outlets and banking and financial services have been complicit in pushing the market and exploiting the war-torn population.

Given this easy access, the public, youth in particular, tend to consume with compulsion bringing about changes in their thoughts, attitudes and activities. While in any society after a prolonged deprivations due to war, such consumption patterns are bound to change. But, in this case such consumption comes in the phase of decreasing local production and few avenues of youth employment.

Employment opportunities are scarce. Many youth dream of migrating to the West or the Middle East as the solution to their economic problems. The few employment opportunities are irregular day-wage labour. Thus, they have increased leisure time and spend it with peers, ‘hanging out’ in public spaces.

In those deprived families and areas without links to outside remittances, the lack of opportunities and a future without jobs also leads to nihilistic life style among youth. In this context, state, foreign and diaspora investment should be towards getting the economy going to create opportunity structures, meaningful jobs and real income to make the future hopeful for the youth.

To be continued next week