Travelling the terrain and through history to understand the country

View(s):There is not one but many ‘Sri Lankas’, one for each individual. This explains why some Sri Lankans love their country while others wish they were born elsewhere; why D.H. Lawrence hated it while Sir Arthur C. Clarke was smitten enough to make it his home.

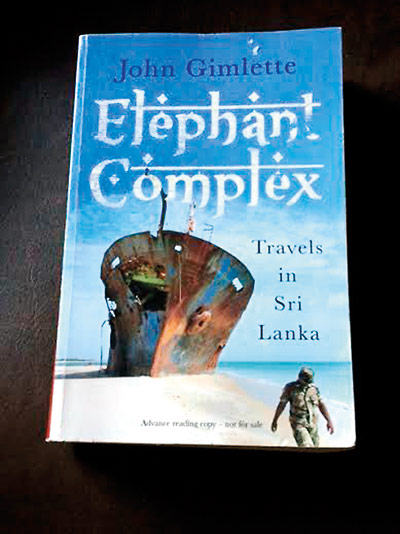

John Gimlette’s Elephant Complex is the latest travel book on Sri Lanka. Gimlette however is no Raven-Hart, that flamboyantly gay writer who filled the pages of his books with remarks on the beauty of Sinhalese men.

Neither is he W.T. Keble who, in stark contrast, wrote about a quaint and romantic land and people in the classic style of H.V. Morton.

Neither orgy nor opiate, Elephant Complex is a quest to understand the country, and not a mere description of it. This is what sets the book apart from the legion of Ceylon and Sri Lanka travelogues.

The book covers Sri Lanka geographically as well as historically in 490 pages. It starts with Colombo and heads to Galle and the South, Kandy and the upcountry, the East, and finally the North.

Gimlette’s Sri Lanka is heavily scarred, unlike the Eden earlier writers have known: Black July, the civil war and the Tsunami among others have taken their toll.

But happily, to Gimlette Sri Lanka is still Paradise, though ‘damaged’. He serves readers with the distinct beauty and character of the country.

Sri Lankans themselves will find Gimlette’s renditions of places from Colombo to the desolate Wanni inspiring and evocative. As his journey unravels, so does the history of Sri Lanka.

Gimlette connects each place he visits with its past, using his imagination to put flesh on the bones left by ancient chronicles, records left by colonial rulers, or memoirs from the war.

He reconstructs at length the Kandyan Wars (and how three great European nations were outwitted by the Kandyans). He also brings to life the long drawn out story of the Sri Lankan civil war.

He charts, too, many other watershed moments in our history assiduously, by visiting the monuments and relics left of them.

His interviews are with a great medley of people: former President Chandrika Bandaranaike; slum dwellers in Colombo; terrorists; writers; cricketers and the ‘the last of the planters’.

Adventurous, intrepid and romantic, he goes in search of the lost “Great Road” to Kandy, and visits a gay brothel in Negombo to investigate if rumours are true and has a close escape from a frisky teenager.

With the impressive minutiae of first hand knowledge and reading, the book covers a vast sweep: Dutugemunu to Mahinda Rajapaksa; Sigiriya to Tintagel.

While many travel writers on Ceylon often tended to trim and twist the country to fit it into their own neat narrative, Gimlette does not hide the incongruities and bafflements he encountered.

At the end of the journey he says, with great honesty, that he is troubled because he is unable to make the kind of authoritative judgments other travel writers had made on the country:

“Perhaps I’d understood Sri Lanka even less than I’d imagined….I lay awake for hours, trying to make sense of the way I felt. The perplexity was easy enough, and so were the twinges of horror, but I also recognized affinity, wonder and regret.”

But it would have been surprising if Gimlette actually managed to sum up his reaction neatly after such a journey into the country’s heart.

After such intimacy with a land so ancient and diverse, you will see it as a vast melting pot, from which you cannot pick up separate colours or entities. So to the question “what does Gimlette come up with at the end of his search?” we can only answer: ‘read the book’.

In Elephant Complex pachyderms are more figurative than real. At the beginning itself, Gimlette draws a parallel between elephant corridors and the history of the island.

Elephants are known to remember and follow the same paths (‘corridors’) from generation to generation, sweeping aside anything that has come to block their way during the long period during which their kind had not used the road. He attributes this to “a great plan of this island (that exists) in the collective elephantine mind.”

Then he draws a parallel between elephant corridors and Sri Lankan history:

“Maybe the human mind works the same way. Looking through Ceylonese and Sri Lankan history, it never feels quite circular.

Rather, there are a recurring series of points of arrival and departure, with everything between lying disrupted and broken.

Civilizations appear and flourish, and there’s a great surge of progress before it all vanishes. No one is quite back where they started, and yet the same story will begin again… ”

He surmises that “perhaps these pathways exist in some great and mysterious map, or perhaps it’s just a state of mind, an elephant complex.”

One of the last observations Gimlette makes is also of an elephant. This one is being bathed by its mahout at Gangarama. “As I peered into (the elephant’s) tiny eye, I couldn’t help feeling that there was something it knew.”

I suppose knowing what that ‘something’ exactly is, would be like finding the Holy Grail: the end to Gimlette’s quest.

| Book facts The Elephant Complex by |