Returning again and again to a familiar landscape

Though she was born in Kuala Lumpur, and has since lived in England, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, Minoli Salgado will tell you her earliest memories are of her grandparents’ home in Sri Lanka. Revealingly, this is a country she feels compelled to return to again and again in her writing.

Minoli Salgado

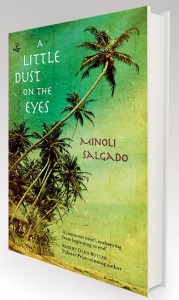

A poet and the author of several short stories, Minoli is perhaps best known for her debut novel A Little Dust on the Eyes, which was recently long listed for the DSC Prize. (The winner of the Prize is to be announced at the Fairway Galle Literary Festival in January.)

The novel follows the twined lives of two cousins – Renu works with the families of the disappeared in Sri Lanka and is only reunited with Savi, who was pursuing a PhD in the UK, when the latter returns for a family wedding.

Together the two confront an increasingly complicated and painful past and when the tsunami strikes, are thrown into even greater turmoil.

An academic with a PhD in Indo-Anglian fiction, Minoli currently teaches at the University of Sussex where she is a Reader in English Literature. She is also the author of Writing Sri Lanka: Literature, Resistance and the Politics of Place.

For this influential study of Sri Lankan literature in English, Minoli analysed in detail the works of eight Sri Lankan writers – Michael Ondaatje, Romesh Gunasekera, Shyam Selvadurai, A. Sivanandan, Jean Arasanayagam, Carl Muller, James Goonewardene and Punyakante Wijenaike.

Here are extracts from an email interview the author gave the Sunday Times:

- You’ve lived in many different countries, but what is it about Sri Lanka that draws your attention as a writer? In your work, you grapple with disappearances, silence and unreliable histories, in what way do those themes reflect your encounters with this island?

Yes, I have lived outside Sri Lanka for a long time and I have always been coming back. Sri Lanka has been a constant in the middle of all the change.

Whenever we were back, my father would take me around the country, re-introducing me to my large extended family. The experience gave me a strong sense of connectedness that has developed beyond family links.

Sri Lanka is a vibrant land, teeming with stories that you move into every day.

I come awake in Sri Lanka. As for my engagement with silence and enforced disappearances, these are shaped by the time I spent in the country in the late 1980s and early 1990s when I became interested in the Mothers’ Front and the example set by Dr Manorani Saravanamuttu. She is someone who spoke out when others did not, someone who spoke truth to power.

- Did Renu and Savi emerge as characters while you were writing A Little Dust on the Eyes? Tell us about their relationship, and how each of their concerns drives the plot forward.

Renu was going to be the main character. I was trying to find a way into her story when I thought, why not write a double narrative, from two different perspectives, one that would broaden the reach of the book and take it outside Sri Lanka.

Savi came to me then. Her specific difficulties, which are tied to her personal losses and wilful blindness to political events, immediately enriched and balanced Renu’s story.

Renu doesn’t have Savi’s personal hang-ups but her search for political answers ends up taking her into a closer knowledge of her family.

Each has something to learn. The personal and the political are intertwined and the close connection between the cousins, as they discover themselves through one another, drives the narrative forward.

- You landed in Sri Lanka a few hours before the tsunami struck. What do you remember of days in the immediate aftermath? In fiction, how does integrating a real tragedy on this scale both challenge and allow for new realities for you as a writer?

This was a terrible time – we all knew people affected. It defies description. As a writer you are looking for a language to make sense of it while also having to acknowledge its resistance to being written about.

I wrote a piece, ‘The Waves’, just days after the tsunami, having visited some refugee camps; it is quite raw, I think, and communicates this difficulty.

I took a different approach in the novel, juxtaposing different voices to show both the struggle for expression and the impossibility of containing the event in language.

The tsunami is narrated through a host of different discourses – journalistic, mythic and scientific, among them – and exceeds them all. Ultimately it is the characters’ experience of the tsunami, each one different and individual, that readers will remember.

- Why do you think the civil war is a preoccupation shared by Sri Lankan writers both residents in the country and in the diaspora?

One of the things that connects us is this shared past. Fiction and poetry are hugely important – vital, I would say – in giving us access to new ways of seeing, writing and bearing witness to this past, in opening it up to scrutiny, challenging official versions, creating channels for communication, forging links in ways that might allow for greater understanding of the differences between, and commonalities of experience.

Literature has the power to transform our relationship to the world.

- Why do you, personally, choose to write about the civil war? As a writer how do you approach topics that may be very contested and emotionally fraught?

I belong to the generation that grew into adulthood with the war. I was an undergraduate when it began so it has shaped my thinking.

I am acutely conscious of the need for an ethical writing of trauma and have tried to address this in A Little Dust by layering the narrative, so that not only the characters bear witness to events but the readers are made witnesses too.

I would like readers to become conscious of their role as witnesses to history, to take responsibility for this.

- You’ve written poetry and short stories and now a novel. How do you decide which format you will work in when you have a story to tell? Does one ever become the other – say a poem feeding into a short story?

I don’t choose the form; ideas come and crystallise around an event, a character, a voice. It makes me think of Tartuffe – you know the bit where Monsieur Jordain says something like ‘What! I have been talking in prose all this time? I didn’t know!

’ You discover the form for a piece as you keep writing. A novel needs planning and historical grounding, while stories and poems can be more ephemeral and intimate. ‘The Waves’ was first published as a prose piece but I later rewrote it as a poem to emphasise the voices that make it up.

- When do you think you will be in Sri Lanka next? Is there another book in the offing? If yes, do you imagine you will set parts of it in Sri Lanka again?

Quite soon, I hope. I have accepted an invitation to participate in the Galle Literary Festival. And yes, I am working on another book. Whatever the primary setting, Sri Lanka is likely to remain a part of my imaginative landscape.