Sunday Times 2

The facts behind the elepant dance

The presence of intricately caparisoned elephants adds glamour to the perahera and brings it fame world over. The elephants marching in the perahera show different types of rhythmical body movements better known as “ali natum” meaning elephant dance. These body movements of elephants sometimes synchronize with the drums played in the perahera. It gives the general public the idea that elephants dance to the music. Generally, moving of the body is started when elephants halt marching and stops as soon as they start walking during the perahera.

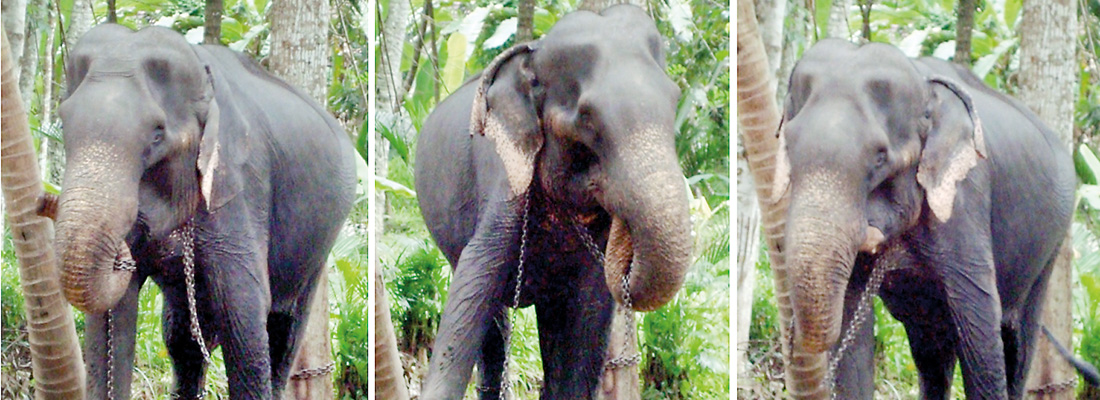

A safari elephant swinging his head from side to side

The scientific community refers to these movements as examples of ‘stereotypic behaviour’ or self-stimulatory behaviour. This behaviour can be seen in elephants at any captive setting, chained or unchained, any time of the day. There is no age limit to this behaviour which is more common among adults. The frequency of stereotypic behaviour can depend on the management practice, season, age, individual character etc. Generally, stereotypies in elephants bring negative image to their management but it might be energetically cost effective to the elephants, though it is yet to be proven. Introduction of enrichment might reduce these behaviours in captive elephants.

The people of Sri Lanka enjoy an extraordinary relationship with elephants and it spans nearly 2,500 years according to the Mahawansa, the oldest and longest chronology in the world. Elephants play a significant role in culture, folklore, tourism, religious and state functions in the country. They have a unique place in buddhism. Conceiving of prince Siddhartha was seen by queen Mahamaya in her dreams as an entrance of a white tusker. According to Jataka tales, Siddhartha Bodisathwa has been born as elephants in his previous lives. Some encounters of elephants and Gauthama Buddha has also been mentioned in recorded Buddhist history. In Chulla Hatti Padopama sutta, discourse by Arahat Mahinda Thera to king Dewanampiyatissa, describes how to identify the enlightened one by taking the simile of witnessing the majestic elephant itself, without being misled by the elephant’s foot print or tusk marks. The Hindus in Sri Lanka also show a great respect for elephants as the God Ganesh has the head of an elephant.

Captive management of any animal is noteworthy as a means of ex-situ conservation. A major goal of captive animal management should be to promote the expression of natural behaviours that they exhibit in the wild although the natural conditions cannot be precisely recreated. Ensuring the wellbeing of captive elephants is challenging in terms of husbandry, cost and public perception. Objectively quantifying elephant welfare is also a considerable task as interpretation of animal behaviour is subjective most of the time. Captive elephant holdings currently found in the country are Pinnawala Elephants Orphanage (PEO), the National Zoological gardens and Elephant Transit Home. In addition, Buddhist temples including the Temple of the Tooth and Devala, and private owners claim the authority for about 162 elephants around the country (Personal communication by Mr. S. Rambukpotha).

Elephants exhibit different types of activities such as feeding, bathing, social interactions, communication, mating, and muscular activities. In the case of captive elephants, these activities or behavioural patterns can change with sex, age, individual history, family unit, geographical region, climate and management practice. Among these behaviours, this document articulates stereotypic behaviour, a type of behaviour that elephants perform in captivity. The content of this article is mainly based on the results of an observational study done on captive elephants at PEO, 2 safari settings, Kandy Perahera in Sri Lanka and Center for Elephant Conservation in Florida, USA (CEC).

Stereotypic behaviour is defined as any repetitive invariant body movements or repetitive movement of objects that has no obvious goal or function. This behaviour can also be seen in people with developmental disabilities and confined captive animals. The frequent types of stereotypies exhibited by elephants are: weaving (Repetitive swinging of trunk and head from side to side), head bobbing/nodding (moving head up and down in a repetitive manner), weaving while lifting a foot (moving body from side to side repeatedly, usually with one foot off the ground and most of the time it is the forefoot), biting the perimeter bars or fence and throwing and retreiving objects.

Several studies documented stereotypic behaviours in elephants brought to peraheras. Video recordings (in a stretch of about 20m) of elephants parading in the Kandy Perahera in 2009 and 2010 (71 elephants each year) revealed that 14% and 20% of elephants performed at least one type of stereotypic behaviour respectively (Athutupana, 2012). These values were much lower compared to the results obtained in a previous study in 2001 by Kurt and Garai. They reported that about 40% of the elephants weaved while marching slowly in the Kandy Perahara. Disparity of the results may be due to the place where the study was carried out. Weaving while lifting a foot was the most common type of stereotypic behaviour in 2009 and it was replaced by weaving in 2010.

The back legs of the elephant are fettered while they are marching. Therefore the process of forming the stereotypy may be triggered by their limited movements. Yet, none of the elephants carring the relic caskets exhibit stereotypic behaviours while marching in the perahara in the above years. Moreover, Abeysinghe et al. reported that 37.3% of the observed elephants performed stereotypic behaviours during processions in Walpola, Veyangoda, Vishnu and Kandy in 2009. However, these behaviours are not restricted to perahera elephants. According to the study done in 2009-2010, all the elephants observed in safari settings performed at least one type of stereotypic behaviours. It was seen in 34.6% of elephants at the PEO but the results could change if the elephants were observed when they were tethered in the sheds.

Stereotypic behaviour can be initiated or induced with changing of management practice. For instance, a sub-adult male and a juvenile male started to perform stereotypic behaviour with the beginning of training. No type of stereotypic behaviours was displayed by them when they were in the yard with the herd. This is probably due to the commencement of chaining during the day time which they did not experience before. In addition, three safari elephants performed less stereotypic behaviour when they were brought to perahara. In this setting, they were able to associate more with other elephants compared to a safari environment.

The extent to which the stereotypic behaviours are performed can mainly depend on the management practice, age, season, social environment and individual character. Elephants living in a group spend little time on stereotypic behaviours whereas elephants not living in a group tend to perform more stereotypies. Possibly the environment of individually fettered or housed elephants is fairly static and elephants are not able to socialize with other elephants. Restraints may inhibit the ability of elephants to engage in activities like locomotion, play and social interactions and it may increase stereotypic behaviours. However, same behaviours have been shown by elephants observed at CEC although they were unchained and dwell in yards or paddocks during the observation period.

Stereotypic behaviours are observed mostly among adults and it was low among juveniles. The majority of elephants showing sterotyic behaviours in the perahera were adult males (70% in 2009 and 57% in 2010). Most of the adults have participated in the perahera in previous years. Therefore, they might know the routine and hence anticipated to finish the procession to get their food. For juveniles and sub adults, perahera may have been a new experience and they might have been excited about the decorated surroundings. Therefore, exploratory behaviours were more pronounced than stereotypic behaviour among them. None of the calves and juveniles observed at the PEO performed stereotypic behaviours when they were in in the yard. However, Kurt and Garai (2001) reported that captive neonates and infants spent much more time in weaving than wild ones. This raised a question on whether calves and juveniles perform stereotypies in the wild. However, quantitative data regarding stereotypic behaviour in wild elephants are not found. McKay (1973) reported an incidence of wild elephants performing slight bobbing of their heads and bodies while they rest. According to him, this was very similar to the pattern called “weaving” but not as pronounced as ones displayed by captive elephants.

Social enviroments are also important when concerning the stereotypies. Kurt and Garai (2007) reported that, elephants born in PEO who grew up in close contact to their relatives showed less stereotypic behaviour than orphans. They further noted that, elephants stopped weaving when they reached their social partners and this led them to conclude that stereotypies are formed by lack of adequate social partners. Elephants at CEC are housed individually or as a couple in a yard and this lack of social partners may trigger stereotypic behaviors in them.

Several factors can elicit stereotypic behaviour in elephants and it is not necessarily the chains. One such thing is anticipation. They weave whenever they have to wait for something or when expecting something. For instance, food, water, enrichment, taking to the yard/river or when they are expecting to be cleaned can trigger stereotypies. Even the elephants in a group could display stereotypies when separated from the main herd, change the place and time of tethering and usual daily activities are disturbed.

There is no exact time of the day that elephants show stereotypies. Elephants observed in safari one spent 15.4% of their time performing stereotypic behaviour during the day time and only 0.8% at night. In safari two, elephants spent 22.1% and 11.9% of their time performing stereotypic behaviour in the day and night respectively. The reduction at night was mainly because they spent more time on feeding and fanning their bodies with branches apparently to dislodge biting insects or to prevent them from landing on them. It would be interesting to examine the night time behaviours of elephants at PEO after they are tethered in the sheds.

Stereotypies might be inherited or learned. One female elephant in a safari exhibited the same type of stereotype as her mother, which was head bobbing. This idea is further supported by Mason (1991), stating that the stereotypies by an individual may not necessarily be an accurate reflection of its welfare at that specific point in time, but may instead reflect its past history or inheritance. Before coming into conclusions, this requires further investigation using parents and offspring that perform stereotypic behaviour.

Dr. Rukmali Athurupana lives in Japan and this article is based on

M.Phil research done from 2008-2012.