Columns

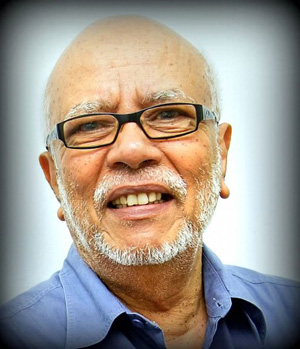

How trailblazer Rex de Silva made journalism’s sun shine

The year was 1964. Clad in blue jeans, Rex de Silva walked into the office of the chairman of M. D. Gunasena bookshop in Olcott Mawatha even without a by your leave, introduced himself, said he was a Catholic and a member of Catholic Action and asked the boss of this predominant Sinhala Buddhist publishing company, Sepala Gunasena whether he could be found suitable employment in the organisation.

Intrigued at the nerve of the young man with long hair and unkempt beard — a typical flower power kid of the sixties in full bloom — to come and present his Catholicism as his credentials and Catholic Action as his work experience for employment in a staid book publishing house regarded as a Buddhist bastion, Sepala Gunasena was immediately captivated by the no holds barred full frontal approach which bore the stamp of frank boldness and redeeming originality.

He was immediately hired. But sensing perhaps the dynamics of the book publishing world may be far too tame to satisfy the throbbing dynamism the young man exuded, Mr Sepala decided to try him out at the newspaper company, Independent Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of the Gunasena Group, which he had founded three years earlier; and which published the Sinhala daily the DAVASA and the English daily the SUN and the Sinhala and English Sundays the RIVIRASA and WEEKEND respectively.

Charles Rex de Silva was 23 years old. At Independent Newspapers Ltd (INP) he was employed in the advertising department as a trainee advertising executive. This was his first steady job and Rex began to demonstrate his strong work ethic that was to become his hallmark trait throughout his life. And it paid dividends.

That year on Christmas Eve, Sepala Gunasena made his usual night time visit to the works department where the papers are composed in hot metal, assembled and made ready for printing. To his surprise, he found Rex in the works department poring over some galley proofs and asked him why he was still at work at so late an hour and not celebrating Christmas Eve with the rest.

“I am going though the proof of this advertisement, sir,” Rex replied, “just to make sure there are no mistakes in it.” The chairman wished him a merry Christmas and went home. If Santa Clause did not arrive that night for Rex, his Christmas present was hand delivered at the start of the New Year when he received notice that he had been transferred to the news desk of the SUN newspaper.

He had arrived at the foothills of journalism’s Himalayas and his spectacular ascent to the summit was swift. His journalistic talents were also spotted by the doyen of journalists, D. B. Dhanapala, the Editor in Chief of the newspaper group who corralled him to the WEEKEND sub desk. Within two years, Rex de Silva became the youngest editor of a national newspaper in Lanka when he was appointed the editor of the WEEKEND. And the tabloid Sunday became the ideal vehicle for him to mount to further flaunt the flamboyant style and inborn talent that had won him his spurs.

Rex de Silva: Journalism’s Shining Knight, who used his pen as his sword

It was the swinging sixties. The revolution had just started. It was the new era of free love. Of Rock ‘n Roll. Of Flower Power, the Beatles and Hare Krishna, Hare Ram. A time when the world was splitting up. The Age of Aquarius when old icons were being smashed to smithereens. And a new world order was evolving. It was a make love-not war, live and let live, cool and groovy, psychedelic world where all you needed was love. And Rex epitomised it. He was the free spirit of the age of the ‘now’ generation, not only ‘with it’ but ahead of it. And the WEEKEND reflected it.

But alas, the dusk to dawn local party couldn’t make it through the night. Over Lanka, grim shadows were falling. Inflation was galloping. Unemployment was rising. Youth frustration was fermenting. Ill winds were blowing. And Rex stepped out of his blue suede shoes to break even more alarming news to the nation. In an exclusive report he broke the story in the WEEKEND of a ‘southern rebellion brewing’ and how intelligence had been received of a planned insurrection. A year or so later in 1971, April the JVP struck.

Even though the insurrection was quickly quelled, the damage had been done to the Lankan psyche. In the aftermath of the revolt, the nation came to be ruled under emergency law. Independent Newspapers which had contributed in no small measure to bring the SLFP coalition to power soon began to reflect the growing public antipathy to the government. In 1973, the country’s biggest newspaper group Lake House was nationalised and it fell to Independent Newspapers to singlehandedly bear the torch of press freedom in Lanka, which it did fearlessly until its lambent flame was snuffed by the government when it sealed its presses in April 1974.

But before the sealing finally took place and whilst the Damocles sword dangled over their heads for months on end, Rex de Silva and the other editors and journalists at INP did ‘not go gently into the night but raged against the dying of the light’. There were no private television networks then, no private radio stations, no civil rights movements, no facebook or twitter or online websites or whatsapp. There was not even a credible opposition with the UNP reduced to mere 17 seats as against the SLFP-LSSP-CP coalition’s 116 seats in the 1970 election. The battle had to be fought alone. There was no cavalry to call for support.

Apart from the government-owned radio and the government owned Lake House, the only medium struggling to defend the blatant assault on freedom of expression was the SUN group of newspaper. Bolstered by the tough uncompromising stand taken by the publisher Sepala Gunasena not to yield to political pressure but to remain independent, Rex de Silva and the other editors of Independent Newspapers’ publications waged a valiant battle to keep the sun from going down on the nation’s freedoms.

Twenty-five years after becoming an independent country, this testing period marked the turning point in the history of Lanka’s newspapers where the battle for press freedom was removed from Colombo’s drawing rooms to the streets; and it was here that Rex de Silva found himself on with his gloves off. This episode revealed that the right of the citizenry to exercise the fundamental freedom of expression could no longer be taken for granted as it hitherto had been taken but was one which had to be vigorously defended at all costs against all governments harboring dictatorial tendencies. It was Lanka’s Magna Carta in the making; and the cataclysm demonstrated that the Lankan journalist was no purring pussycat but could turn tiger when his back was forced against the wall. The mettle had been tested and had not been found in want.

Sepala Gunasena’s refusal to bend his knee before an all-powerful government and compromise on his principle of publishing only on his own terms in the public interest or not at all, earned him the international honour of being awarded the Commonwealth Press Union’s Astor Award for defending press freedom in Lanka. But as Sepala Gunasena, who passed away in 1993, would be the first to proclaim, the honour belonged to all — to all those unsung martyrs who unswervingly rose united to brave the challenge and opted to take up the gauntlet than genuflect at the altar of deified political power. By their willingness to sacrifice their all in the defence of press freedom, they forged a new culture of media freedom which demanded eternal vigilance and readiness to defend the right to free expression as the price of civil liberty.

Darkness had fallen; and for the next three years the newspaper group would remain sealed. However, in 1975, Sepala Gunasena started a news magazine which was printed and published by the book printing arm of the Gunasena Group, M.D. Gunasena Printers Ltd. The magazine was called HONEY and was modelled on the WEEKEND giving a mixture of news and features. Rex de Silva was appointed its editor. These were dangerous times. The government had postponed elections and ruled under draconian emergency laws. Press freedom was almost nonexistent.

But Rex de Silva did not fear nor falter to rise to the challenge, even at the risk of arrest. Together with his long standing Sun colleague Iqbal Athas who was Deputy Editor of the magazine, he made do with the limited resources available and broke through the eclipse with at least a few rays of sun. During this period, he married his childhood sweet, Ranjini, the girl next door who took permanent residence in his heart. He felt himself drawn towards the philosophy of the Buddha and also developed a mystic faith in God Kataragama whom he regarded as his guardian deity.

In 1977, the government, finding unable to continue with the break-up of the coalition, dissolved Parliament and called for fresh elections. Independent Newspapers had been sealed under emergency laws which had to be ratified each month. With Parliament dissolved, the emergency laws lapsed due to non-ratification, resulting in the automatic unsealing of Independent Newspapers. Sepala Gunasena was now free to publish his newspapers on his own terms and his editors free to edit without any political interference.

After three years, the long night of darkness was at an end. A new dawn was about to break and a new sun was rising. Starting as a trainee ad executive Rex had become a reporter, sub-editor, chief sub-editor, deputy editor, and Sunday editor. Now at the age of 36 he was appointed editor of the daily Sun. He had come a long way and the experiences he had gained in his rise to the top now stood in good stead to help him meet the many challenges to press freedom under a new right-of-centre government in power with an executive president at the helm commanding a five sixth majority in Parliament to boot.

If threats to freedom of the press from the government were bad enough, the outbreak of Tamil terrorism in 1983 further exacerbated the crisis, not to mention the JVP terror campaign at the tail end of the eighties. Rex’s impartiality, his integrity, his honesty and his sense of fair play were the enduring totemic icons carved on his balancing pole as he walked the tight rope of Lanka’s journalism.

During his tenure as Editor of the Sun, he not only edited the paper brilliantly but also turned the environ to a school of journalism, and those who passed through the groves of his academe imbibed deep the heady draughts of journalism’s potent nectar proffered to them without stint by its finest practitioner. Many of them today hold senior journalistic positions in major English newspapers here and abroad including the posts of editor, deputy editor and news editor.

In the mid eighties Rex de Silva was appointed as a director of Independent Newspapers Ltd. His efficiency, his acumen coupled with his loyalty made him my father Sepala Gunasena’s indispensable right hand, his Sir Lancelot, his knight in shining armour who occupied the foremost seat at Camelot, irrespective of where he sat at the round table. To me, Rex de Silva was my journalistic mentor and yet I can find no words today to express to that exquisite degree the deep regard and affection with which I, who knew him from my childhood days, held and still hold him.

Contrary to the popular notion, Rex de Silva never left Independent Newspapers. In 1989, with his two sons Nishan and Dilan growing up and family obligations mounting he was fortunate to secure an assignment in Brunei to edit the Borneo Bulletin for a period of two years and transform the paper from a weekly into a daily newspaper. He applied for a two year ‘sabbatical’ leave which Sepala Gunasena immediately granted. In 1990 he left for Brunei after handing over the stewardship of the Sun to me to act as caretaker editor until he returned home to resume command.

But alas, it was not to be. Insidious forces were at work threatening the independence of the newspaper group. Mr. Sepala decided to close down his papers rather than see its independent image traduced in the dust. The Independent newspaper group ceased operations on December 26, 1990 after a chequered history of 30 years. Sepala Gunasena thus paid the ultimate price for being independent.

Rex de Silva was a designer creation. The mould was broken after he was fashioned into existence. He was the spirit of his age, unique with his own branded style. He was a Catholic, a Buddhist, a Hindu but above all he was one who cleared his own path to find his way to contentment. For the last six years he had lived a life of retirement in the States in the midst of his beloved grandchildren, enjoying every minute of their company, living the life he never did have with his two sons, strapped as he was to the editor’s chair. Last month when he came to Lanka for a three week holiday, he was scheduled to return on October 24. But illness struck and laid him low but could not stop him from rising from his sickbed to chat with his grandchildren whenever they came on Skype.

Then this Monday, two hours before the dawn, the inevitable happened and Rex de Silva breathed his last at the age of 74. His funeral was held according to his written wishes and the cremation took place at the General Cemetery, Borella at 2pm on the same day. He was a man who had shunned ostentations whilst alive and in death he wished to keep it that way. No black tie and bespoke suit draped his mortal remains but, for the few moment his body was displayed to the family, he was dressed in blue jeans, t-shirt, denim jacket and a baseball cap on his head — the same sixties gear he had worn throughout his life. Even in death, Rex de Silva remained true to himself.

His last request to his friends and colleagues was to remember him as he was when alive; and as long as the black ink flows in the veins of every blue blooded journalist, he will certainly live immortal in the hearts and minds of those he left behind to uphold the integrity and safeguard the independence of the Fourth Estate.

May Rex de Silva attain Nirvana.

| Night Rex became Editor of the Sun March 31, 1977 was the day planned for the relaunch of the company’s newspapers after it was unsealed after three years. It being a weekday, the papers to be published on that day were the Sinhala, English and Tamil dailies, namely the Davasa, Sun and Dinapathy. Hectic activity was taking place in the building on the 30th as the countdown began for the presses to roll that night. Whilst continuing to be the Editor of Honey, Rex de Silva had taken a leave of absence to be in Bangkok and do a short stint at the Bangkok Post where his brother worked. When the summons arrived from his boss Sepala Gunasena to return home, he made his travel plans to land in Colombo on Wednesday the 30th. With the WEEKEND only coming out on Sunday, he guessed he had enough time to edit and produce it. However, arriving at Katunayake Airport, he made a bee line to the newspaper office at the top of Hultsdorf Hill to share in the excitement gripping launch night. Mr. Sepala was in the editorial floor, seated on a chair in front of the desk reserved for the Sun editor, when Rex de Silva arrived with his hand luggage still slung over his right shoulder at around 7 in the evening. In the midst of all the clang and clatter, they exchanged a few pleasantries. Then Rex, obviously tired, asked to be excused stating, “Sir, I will go home now, bathe, change and come a little later to office.” Mr. Sepala gave him a bemused look and asked with feigned brusqueness, “Where the hell do you think you’re going?” and pointing to the empty Sun editor’s chair said, “Sit down and edit your paper.” As Rex de Silva flung his hand luggage to the ground to begin his new duties as editor of the company’s English daily, no doubt he would have felt he was lifting the sun over his head in the manner Atlas was asked to hold the world on his shoulders. But unlike the mythological Titan to whom it was meant to be a punishment, for Rex this new labour would be a labour of love. For he had taken Confucius’s advice to do a job one loved doing, for then one would never have to work a single day in one’s life. The first task was to change the masthead of the paper. It was far too old fashioned for Rex’s liking and he wished to put his own dynamic stamp on the paper from the masthead down, from the word go. A quick search in the library produced the dynamic type face that was more in keeping with the dynamic style of the newspaper Rex wanted to produce. The daily pocket cartoon Pukka Sahib showed the character looking out of the window at the sun shining in the sky and Mr. Sepala wrote the day’s comment: ‘You can’t keep a good man down”. Though it was meant to refer to the paper, it would have been apt for its new editor too. | |

Leave a Reply

Post Comment