News

Maids in misery: From destitution to death

In a hall filled with soon-to-be migrant workers, an instructor runs a multimedia programme on Sharia law. The picture on the screen changes from a hanging to a decapitation, an amputation to a gruesome public stoning.

An instructor at SLBFE runs a multimedia programme on Sharia law for trainees. Pix by Amila Gamage

“These are the laws of the countries where you will be working,” M.H.M Azwer, the instructor, says. He explained what each punishment was meted out for. He shows short films depicting various aspects of Sharia law. And he urges the trainees, whose eyes are riveted on the screen, to follow accepted behaviour while working abroad.

The men and women were participants of a pre-departure workshop conducted for migrant workers by the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE).

First time domestic staff—housemaids—must follow a 21-day course and obtain a certificate which denotes them as “housekeeping assistants”. This credential is a mandatory requirement for SLBFE registration and it is compulsory for those seeking employment in Saudi Arabia.

It is in Saudi Arabia that a 48-year-old (contrary to most reports, she is not 45) Sri Lankan woman now stands convicted of adultery. She is sentenced to death by stoning while the man she had relations with is to receive 100 lashes.

Saudi courts have agreed to take an appeal after Colombo interceded on her behalf. The case will be heard in January, an SLBFE official said.

“The man and woman are Muslims,” the official continued, referring to a document in front of him. “This makes it all the more difficult to save them because they are expected to know the laws and the teachings of the Quran.”

Chandrika Dissanayake and Nilusha Kumari Jayakody

But there is a possibility that the woman used a Muslim name but was of another ethnicity, said Mujibur Rahman, Colombo District Parliamentarian. “We received some information to that effect,” he said. “It is not confirmed that she was Muslim. We also have not been able to find the agency that sent her to Saudi.”

The woman has asked that her identity be kept secret. She is married with children and her husband is unemployed. She was first arrested in April 2014, after her sponsor reported her to the police. Her case was taken up in January 2015 and her sentencing happened four months later.

The Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs was notified in July while its Sri Lankan counterpart was informed in August.

There are other Sri Lankans on death row in the Middle East but this woman’s story has caught the public’s imagination because of the brutal nature of her punishment. Protests were organised on her behalf and an online petition launched.

On the pavement outside the SLBFE on Tuesday, a group calling themselves ‘concerned people’ collected signatures for another petition urging the Government to help save the woman.

A steady stream of passersby stopped to initial the papers that were laid out on a table scattered with jagged stones symbolising the stoning. By noon, more than 2,000 signatures had been collected.

The signature campaign against the Lankan woman condemned to stoning in Saudi Arabia

One of the signatories was 39-year-old Nelum Thushari. Whatever the fault the woman might have committed, she said, “You mustn’t stone a person to death. She is a mother. It is economic hardship that forces these people to go abroad. It’s not that they like to go.”

Kumari Kumaragamage, an activist writer, was one of the organisers of the petition event. She spoke of the plight of women who travelled to the Middle East on work. “Some parents say that they only hear of their daughter after she is dead,” she said.

“These women go through so many problems. But when they come to the Bureau with a problem, they are sent from table to table with no solution offered.”

The Sunday Times met two such women—Chandrika Dissanayake and Nilusha Kumari Jayakody—in an SLBFE corridor this week.

They had returned prematurely from Qatar (they had not liked the homes they were assigned to) and were trying to claim insurance from the Welfare Division. After filling several forms, they were sent away gutted because they could not prove that they had suffered hardship in Qatar.

Some of the difficulties are perennial. Placement in decent homes remains an overwhelming challenge. Large numbers of domestic workers leave their first assignment and seek others because they are unhappy.

There is a clear deficit between expectation and reality. As a result, some women circulate among several residences before settling in one or making their way back to Sri Lanka.

Chandrika Dissanayake from Kolongahawatte, Bibile, falls into the second category. She is a 28-year-old divorcee. She has a son of 12 who has been ordained a priest. She returned from Qatar last Sunday and had hoped to claim insurance from the SLBFE.

It is not the first time Chandrika had been abroad. She worked in Saudi Arabia for two years, in Kuwait for one-and-a-half and in Dubai for one. But her Qatari stint, which began on September 30 this year, ended badly. Her agency placed her in a total of six residences within one month.

She then spent a month in a boarding. She received no wages and the SLBFE turned down her insurance claim.

The story does not always end this way. There are thousands of domestic workers who lead successful lives. But the tales of misery are too numerous to ignore. Even last week, 83 maids were brought back to Sri Lanka from Kuwait.

They wept as they were interviewed by journalists. Reports of beatings, denial of food and drink, repression and overwork are common. Such reports have led to a predictable response: Prevent our women from going to the Middle East.

Harini Amarasuriya, a Senior Lecturer at the Open University of Sri Lanka, calls this, “A very knee-jerk reaction to a complicated issue”. “It offers some kind of relief to the conscience to say ‘Stop the women from going’,” she observed. “But it doesn’t stop the women’s problems or reasons for why they are going.”

Dr. Amarasuriya pointed out that there were other grounds—less highlighted even by rights groups—for why women might be seeking employment abroad.

“There are many who actually make an informed decision to leave this country because they face domestic violence or harassment at home,” she explained.

Agencies confirm that many female domestic workers come from broken homes, are divorced or have suffered violence. Sri Lankans—while criticising how other countries treat their women—must also take a long, hard look at how women are treated here.

As long as the issues surrounding female migration are studied in vacuums, the vicious cycle will continue. The airplanes will keep bringing disappointed, weeping souls back.

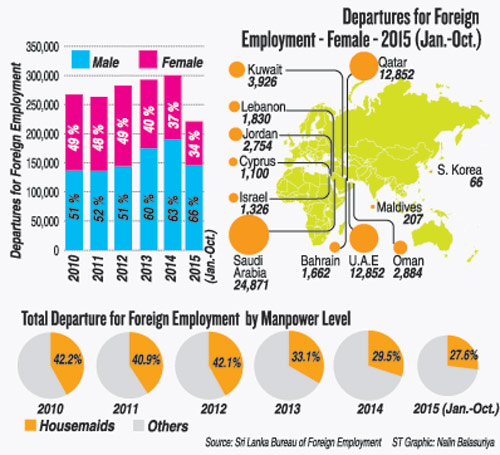

| Saudi Arabia opens door wide for Lankan workers Saudi Arabia is still the leading recipient of female domestic workers from Sri Lanka, statistics from the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) show. Last year, 38,529—nearly 40,000—women are recorded as going to Saudi Arabia for work. The number of men is higher: 41,951. Together, that country received a total of 80,480 Sri Lankans in 2014. This year, from January to October, Saudi Arabia absorbed a total of 24,871 women and 36,935 men—a total of 61,806. The country that received the second highest number of female domestic workers is Kuwait. In 2014, it took in 27,708 women and 15,844 men (a total of 43,552). But the number of those that returned prematurely was not reflected in the statistics. According to the Central Bank’s Annual Report, worker remittances amounted to US$7 billion in 2014. There is no breakdown for how much came from the Middle East. But with numbers like these, it is unlikely that the Government will ever impose a ban on women working abroad. But a partial suspension has been attempted. Since August 1, prospective women domestic workers must produce a certified “family background report” that shows they do not have any children under the age of five. Those with older children must ensure they will be “in safe hands” during the absence of the mothers. This requirement has been challenged in court on the grounds that it is discriminatory of women. The case is pending. The ban has had limited success. Agencies confess that other routes are being found to send women with young children abroad. They might not register with the SLBFE while some travel on visitor visas and get their employment documents sorted out at the destination. “I know others who go to India on a visitor visa and get an employment visa from there,” said one agent, requesting anonymity. |