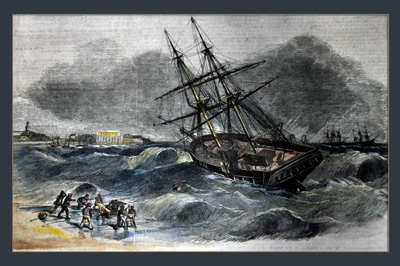

The wreck of the “Hebe” in the Colombo Roads

When ‘H’, a retired member of the Ceylon Civil Service, was handed The Illustrated London News for Saturday, October 2, 1852, by his Man Friday at his house in Bayswater, he marvelled at the way the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine was collated in such a jiffy.

The Illustrated London News was a publishing phenomenon. The inaugural issue, which appeared on May 14, 1842, sold 26,000 copies. Ten years later, the copy that ‘H’ received was one of 200,000 sold every week, an enormous figure compared to other contemporary British newspapers. Contributors included Robert Louis Stevenson, Thomas Hardy, J. M. Barrie, Wilkie Collins, Rudyard Kipling, G. K. Chesterton, and Joseph Conrad. It appeared weekly until 1971, less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in 2003.

The Illustrated London News was a publishing phenomenon. The inaugural issue, which appeared on May 14, 1842, sold 26,000 copies. Ten years later, the copy that ‘H’ received was one of 200,000 sold every week, an enormous figure compared to other contemporary British newspapers. Contributors included Robert Louis Stevenson, Thomas Hardy, J. M. Barrie, Wilkie Collins, Rudyard Kipling, G. K. Chesterton, and Joseph Conrad. It appeared weekly until 1971, less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in 2003.

It wasn’t until ‘H’ enjoyed his China tea in the afternoon (he never lived to drink Ceylon tea) that he looked at The Illustrated London News in earnest. He glanced through it initially before something of interest caught his eye – a wood engraving (the prime means of illustration at that time) titled “Wreck of the English Brig Hebe in the Colombo Roads, Ceylon”.

The artist had recreated a dramatic scene: the Hebe stranded parallel and surprisingly close to the shore, listing heavily among the artist’s impressive rolling breakers. On shore can be seen a group of ten figures, most desperately pulling hawsers attached to the Hebe, but two, one hanging on to his hat, appear to be giving the orders. On the extreme right, further out in the roadstead, two larger ships ride out the storm, and on the extreme right is a glimpse of Colombo.

Hippolyte Silvaf

The paper informed its readers: “The accompanying illustration is from a sketch by Hippolyte Silvaf, a young French artist, residing at Colombo”. According to Ismeth Raheem in his “Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings, Engravings & Drawings of Ceylon by 19th Century Artists” (1986), Hippolyte Silvaf was born in 1801 (and therefore not “young” as described in the paper) and was a “French European from Pondicherry”.

“The origin of the name,” Raheem states, “is a curious example of patronymic formed out of a familiar Portuguese name. Having the same name as his father, the artist always signed ‘Hippolyte Silva.f’. The letter ‘f’ was added as an abbreviation of the French word ‘fils’ or ‘son’. But it was misunderstood and the letter ‘f’ was assumed to be part of the name.”

Silvaf arrived in Ceylon during the early 1820s and “set himself up as a portrait painter and worked in different media including oils, miniatures on ivory and coloured crayons. The idea of painting portraits for private sitters and patrons hardly existed at the time in Colombo.” As a result Silvaf struggled to survive, so in 1834 he opened the earliest art school in Colombo at his house in 1st Cross Street, Pettah.

In 1839 he completed a set of drawings of Ceylon costumes, dedicated to the recently retired Governor, Sir Robert Wilmot-Horton, in the hope of assistance in the cost of publication. That never happened. So, as Raheem comments: “The drawings, which were valuable pictorial records of a period of rapid social change, remained unknown and unpublished [until] 1861, when fifteen select wood engravings appeared in The Souvenirs of Ceylon, by compiler A. M. Ferguson.”

Due to lack of patronage and the ultimate failure of his art school, Silvaf and his talented family – his wife and daughter were accomplished players of the piano and guitar – moved to Kandy around 1854. He set up another school, for art and music, and began to create drawings, paintings and wood engravings of views of Kandy. In addition, the scene of the first locomotive on its journey to Kandy was sketched by him.

In 1986 Raheem remarked: “Though it is recorded that Silvaf was a prolific painter of natural history subjects, very few have survived.” But ten years later, Rohan Pethiyagoda and he revealed in their “Hippolyte Silvaf and his Drawings of Sri Lankan Fishes” (Journal of South Asian Natural History, February 1996) that one of those subjects had come to light.

These 600 drawings were mentioned in J. Emerson Tennent’s Sketches of the Natural History of Ceylon (1861). The author quotes the eminent biologist T. H. Huxley, a staunch supporter of Darwin: “Every drawing was made while the fish retained all the vividness of colouring that becomes lost so soon after it is removed from its native element; and when the sketch was finished, its subject was carefully labelled and preserved in spirits and forwarded to England, so that at the moment the original of every drawing can be subjected to anatomical examination.”

Some achievement indeed, but no mention is made of the artist or the provenance of the drawings. Curious, especially as Silvaf had contributed drawings to Tennent’s earlier Ceylon (1859). Why did the meticulous Tennent not give credit to someone he must have known?

Moving forward in time, Pethiyagoda and Raheem explain: “The collection of fish drawings, which had been offered to the British Museum in 1986, was not noticed by us until 1992, when it came up for sale in Amsterdam. The collection was eventually procured from Wheldon & Wesley Limited of the United Kingdom by the Wildlife Heritage Trust for the National Museum of Sri Lanka”.

The fate of the specimens remains a mystery.

Silvaf died in Negombo in 1879. Although he was buried in the Roman Catholic Church cemetery his grave has not been located by Pethiyagoda and Raheem. Furthermore, and somewhat strangely, Silvaf is not included in J. Penry Lewis’ Tombstones and Monuments in Ceylon (1913), usually a researcher’s goldmine, a most astounding and invaluable compilation of biographical information.

Hippolyte Silvaf remains an enigmatic character. Sadly much of his work has been lost, but what is extant demonstrates he was one of Ceylon’s most important artists of the 19th Century. Because of the sheer number of copies of The Illustrated London News printed, “Wreck of the English Brig Hebe in the Colombo Roads, Ceylon” has become Silvaf’s most proliferated illustration.

Exquisite hand-tinted copies are still available. I acquired mine in 1998 for Rs 3,500. But the original black-and-white version from the paper is more common, on sale today for around $20. Furthermore, it is available as a poster for $50, as a stock photo, and can be licensed from Getty Images for $450.

The Colombo Observer & A.M. Ferguson

“We find in The Colombo Observer, just received,” ‘H’ read, “the following account of a gale at that port, which nearly equalled in violence and destructiveness that of May, last year.”

‘H’ was in Ceylon in 1834 when the daily newspaper The Observer and Commercial Advertiser, better-known as The Colombo Observer, began publication, and had known the editor and proprietor, Dr Christopher Elliot. A nominated member of the Legislative Council, Elliot’s radical views made him unpopular with the colonial establishment for his criticism of Governor Sir Robert Wilmot-Horton’s administration (1831-1837). Indeed, ‘H’ was once rebuked by colleagues for his acquaintance with Elliot.

‘H’s gaze drifted to the end of the report to find that it had been “communicated by Mr Ferguson, of The Colombo Observer”. Alastair Mackenzie Ferguson joined the staff of the newspaper in 1846 after ‘H’ returned to England. A. M. Ferguson, as he was commonly known, became the editor and proprietor in 1859 after the death of Elliot, changed the name to The Ceylon Observer in 1867, and made a significant contribution to the development of journalism in the late 19th Century.

“On Sunday, July 11, when the Agrippa anchored in the roadstead, the sea ran so high that a boat of eight tons burden, bringing some of her passengers onshore, was nearly destroyed in crossing the [sand] bar,” Ferguson’s report began. “She was thrown so completely on her beam-ends, that two of the rowers were washed out; but these men being perfectly at home in the wildest surf, ran no risk.

“The wind and sea continued rising until Thursday night, the 15th, when a strong north-west wind set in; and during the night, the English brig Hebe, partially laden with oil and plumbago, began to drift shoreward, in the direction of the spot where the unfortunate Colombo went to pieces last year.”

Being a classics scholar the name Hebe was no mystery to ‘H’: she was the Greek goddess of youth, daughter of Zeus and Hera, cupbearer for the gods and goddesses of Mount Olympus, serving their nectar and ambrosia. He remembered that liberated prisoners hung their chains in the sacred grove of her sanctuary at the Greek city of Phlius.

“In the course of the night,” Ferguson continued, “one of the sailors volunteered to swim ashore with a rope. He was allowed to make the attempt, but was not again seen or heard of. By daylight the Hebe had struck, and standing side on, the doubling of planks on the weather side soon started, and the sea began to dash over her. The master and crew got safely on shore by means of a hawser stretched from the ship.”

‘H’ realised this was the scene depicted in Hippolyte Silvaf’s engraving.

“It was feared at one time that the masts would come down and that the vessel would go entirely to pieces, but the weather subsequently moderated, and on Saturday morning persons were able to go on board and take means to lower the spars.”

James Steuart

The identity of those in charge of the rescue in the illustration was identified: “We were glad to observe that Master Attendant Steuart was present at the scene of the wreck, and active in saving the lives of the people on board. He was accompanied by Mr Saunders, collector, and Mr Hallifey, the head clerk, Customs Department. The captain was the last to leave the vessel.”

Master Attendant James Steuart had begun his duties in 1825, ‘H’ remembered. What ‘H’ did not know that day, later notified in Lewis’ Tombstones and Monuments, was that Steuart retired two years later in 1855, died in 1870, and was buried at St Peter’s Church, Fort.

Lewis quotes Ferguson, probably from the Illustrated London News, regarding Steuart: “He wrote An Account of the Pearl Fisheries of Ceylon, published in Colombo in 1843, and Notes on Ceylon and its Affairs, published in London in 1862. Steuart Place, Colpetty [Kollupitiya] is named after him [and remains so]. He was a man of considerable ability and of active habits, combining as he did the functions of merchant, banker, and boat-owner with those of Master Attendant and Superintendent of the Pearl Fishery.”

The Inquest

‘H’ learnt that on Saturday the body of the seaman was washed ashore and a coroner’s inquest held. “From the evidence adduced, it appeared that when the vessel struck, about 1 a.m., those on board held a consultation as to what was to be done. The general opinion was that they should remain by the ship till daylight. The captain, however, suggested that if they had a line from the shore, those who could not swim might escape, when a young Prussian, named Garkke, volunteered to swim ashore.

“He lowered himself into the sea with the lead-line, which the captain payed out after him, till he came to the end; when, supposing that the sailor must have been on shore but had let go the line, which appeared to have been carried seaward round the vessel, he (the captain) threw away his end also.

“This the captain subsequently explained: He could see nothing, but when all the rope was payed out, he thought that if the man were still struggling in the water, he would be drowned before he (the captain) could draw back the line; or, if it were made fast to the ship, the man could not get on shore, and would therefore be drowned.

“The best chance, therefore, for the sailor if the line was fastened to him, was to let it go, as he might still possibly get on shore. The captain, therefore, concluded that he ought to let the line go; and certainly under the circumstances it appeared the most reasonable conclusion.”

The jury returned the verdict “That the deceased William Garkke was accidentally drowned, while endeavouring to reach the shore with a line, in order to save the lives of those on board the wrecked brig Hebe”.

The Colombo Roadstead

Ferguson then turned his attention to the scene of the wrecking and Colombo. “As the roadstead of Colombo takes a semicircular sweep, the view includes Customs-House Point, with the lighthouse, and flag staff, all within the walls of the Fort. The town, which is large and scattered (embracing an area of nine miles [14 km], with about 45,000 inhabitants), extends considerably beyond the scene of the wreck.

“From a constantly shifting sand bar at its mouth it does not admit of the entrance of large vessels. This bar forms a harbour for vessels of small tonnage, such as carry on trade with India. There is no harbour at Colombo for large vessels; but the roadstead is, with good care, so safe that events of the kind now recorded are rare. Previous to the loss of the Colombo last year, an interval of more than fifteen years has occurred without a single wreck.”

‘H’ had invested in the flourishing coffee industry (but died before the crash), so was comforted by the final paragraph of Ferguson’s report. “Fortunately the coffee crop ripens in the best season for shipping; and a good class of boats being lately introduced, and much care taken, the proportion of sea-damaged coffee is now very small. Coffee, in the Ceylon trade, has rapidly taken over the position occupied by cinnamon and pearls. In 1836, only 60,000 cwt of coffee were exported from Ceylon. The crop of this year [1852] will exceed 400,000 cwt.”

‘H’ finished his tea and decided to make one last journey to Ceylon. Such was the power of Silvaf’s depiction of the wreck of the Hebe and Ferguson’s reportage.