Wrestling with the word and the world

When Jeet Thayil was 13 years old, he bought a copy of Catch-22. His father, the noted journalist and editor TJS George, did not approve. When he found Heller’s book, he confiscated it.

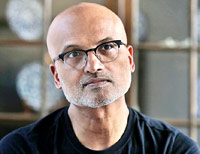

“It’s what you do”: Jeet Thayil. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Thayil went out and bought another. Enraged, believing the book to be inappropriate teenager, and certainly for one who was already pushing the boundaries of authority in uncomfortable ways, his father actually tore the second copy.

Thayil remembers that his parent felt awful afterward – books were revered in their house. But it was still a lesson to him that reading could be a subversive act.When Thayil brought home a third copy of Catch-22, he hid it very well.

That early recognition of the possibilities for rebellion in between the pages of a book shaped the kind of reader Thayil grew up to be, but lest you judge his father too harshly he is also frank about the challenges he posed his parents – “I was a wild child,” he says.

Casually, the author mentions “being in trouble with the police” at age 15, and by age 19, he had found his way to the opium dens of Bombay.

At 56, Thayil has yet to let life beat the wildness out of him. He is the author of Narcopolis published in 2012 which put him on the shortlist for the Man Booker Prize and won him the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature.

He is far more prolific as a poet having produced four collections of which he considers These Errors Are Correct (2008), his best.

Thayil’s success with Narcopolis wasn’t unambiguous. Readers complained that it was disjointed and rambling. Some reviewers never seemed to get much further than the first line which stretched over six pages with not a full stop in sight.

Evoking the headiness of that first pull on an opium pipe, that sentence is a masterpiece, straddling the line between poetry and prose.

The rest of the book, however, can feel uneven; there are moments of luminescence, but it requires patience to find them.

In one of the wittier meditations on the book, Asian Age’s reviewer Raja Sen’s response to the novel took the form of a single sentence, this one only 679 words long, but still enough to convey his opinion that the ‘confounding volume’ was a‘surreptitiously sucked-in hit that thrills only in bits…but nevertheless a quick ride with true merit and some steam.’

But mixed reviews aside, Narcopolis also ensured that Thayil has spent the last few years talking to journalists about how drugs shaped both him and the city he called home.

Opium exported to China in the 1800s made the British East India Company and a group of Bombay Parsi merchants unimaginably rich, yet by and large the populace remain ignorant of the context of the Opium Wars.

“I think of the opium story as a kind of secret history,” says Thayil. “For me as a novelist, that is a history I never reference in terms of figures and numbers though I knew them.

You can Google that. That’s not what a novel should bring you. I think literature can tell you far more of the truth than the stats ever could.”

Though the novel isn’t an autobiography, Thayil drew on what he had seen and experienced in his time as an addict. He first arrived in Bombay in 1979.

“At the time, I was a reckless 19-year-old, and it felt like I was in the wrong place at the wrong time because there was no way to be in a college hostel in Bombay in 1979 and feel in any way that you were not living outside history.” I am curious what he means by that, and Thayil pauses for a moment, before responding.

“I was a poet. I knew nobody, nobody knew me. I discovered the world of opium on Shuklajistreet, my friends were vagabonds and criminals, most of them are dead today.

I certainly felt like I didn’t matter in the world, and that I never would. I felt absolutely obscure, which poets do in any case, which is what being a poet means.”

Thayil makes no bones that writing Narcopolis was for him the opposite of cathartic. Instead he found himself reliving that time in all its despair and wonder.

Though Thayil, along with Bombay would graduate from the oneiric, almost old-world romance of opium to the much harder and edgier one of cocaine and heroin he remained a high functioning addict, holding down a job as a journalist and successfully concealing his addiction for years.

He attempted to get clean many times, and when he finally managed it, the process was so harrowing, that it may have kept him from relapsing.

Today, Thayil says he is simply bored of talking about drugs. “A lot of the friends I had who were on drugs are now on NA – Narcotics Anonymous.

They do rehab with the same fervour that they used to do heroin. I really think the healthiest thing to do is to stop fixating and simply move on.”

Thayil has moved on not only to prose but to poetry and music. In fact the last time he was in Sri Lanka, he came not as an author but one half of the relentlessly innovative band Sridhar/Thayil – they had only 15 minutes of music then, far too little to please the crowd, but eventually together the two produced an album titled STD.

When Rolling Stone published a glowing review of it, they did so under the blurb: ‘eclectic pop twosome make a sexy mess.’ It is one of a handful of projects that showcases Thayil’s artistry as a performance poet.

An anthology of his poetry was received warmly upon its release in 2015. It evoked a “posthumous feeling” in him, he says.

Having tried and failed to better These Errors Are Correct, he is unlikely to ever publish another collection.

Thayil, who lost his young wife, the writer and editor Shakti Bhatt to a sudden illness, in 2007 was still raw with grief when he published that collection a year later, and its significance in his life remains outsized, not least because the book was dedicated to her.

“We started the Shakthi Bhatt First Book Prize after she died, it was a small thing, the family wanted to create a way of remembering her,” says Thayil.

Shakthi was working on two books when she died. Thayil co-curated the shortlist, though he was not on the jury that chose Rohini Mohan’s book about Sri Lanka, The Seasons of Trouble, as the winner in 2015.

He says that the initial selection of non-fiction books all had one thing in common and it was that they “read like literature, and were books that would last well beyond their topic.” (A previous winner, Samanth Subramanian who won in 2010 for Following Fish: Travels around the Indian Coast is also, by happy coincidence, at FGLF.)

Sometime in 2013, Thayil thought he was ready to publish his second book. He even told journalists it would be called ‘The Sex Lives of Saints’ but a second read convinced him it wasn’t ready yet.

Did he feel terrible as realisation dawned that he would have to rework the book? “That wasn’t the terrible feeling. The terrible feeling is now, two years later, when I still don’t know how close I am to finishing it.”

He is willing to wait it out, to live with the “frustration, no, the self-loathing” rather than send something unfinished to the editor.

If Narcopolis was any indication, when this book is released, Thayil will be put through the wringer again, both the bad reviews and the adulation. Is he prepared?

He feels he has no choice: “It’s what you do. It’s your job. Without it you are nothing. Without it you are worse off. Without it you need psychotherapy. Sustained psychotherapy.”

It is clear that writing, whether poetry or prose, is for Thayil an emotionally turbulent, utterly unpredictable process. He wrestles with it, never certain of the outcome. It is in a memory though that I see most clearly the pleasure he finds in his work.

We end where we began – with him in a room with his father and a book.

TJS George had a wonderful library. Thayil remembers reading the collected works of Dylan Thomas and the hardcover first edition of Ulysses that was his father’s pride.

“He was the first adult who spoke to me intelligently about James Joyce,” Thayil says now. He remembers them dissecting the famously protracted sentence that Joyce concluded Ulysses with.

“He said it with such admiration in his eyes. ‘You know this book carries with it a 40 page sentence.’ Thinking of what Joyce had accomplished, and the respect his father had for the writer, the boy thought simply: “Wow, wow. I want to be that guy.”

When I point out to him that, thanks to his six page long first line in Narcopolis, he did kind of grow up to be that guy, Thayil looks startled for a moment. Then he laughs with pleasure at the discovery.