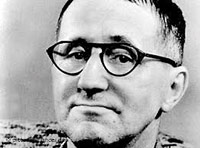

Bertolt Brecht: Did he follow what he said?

(This article is written in commemoration of Bertolt Brecht’s 108th birth anniversary, which falls on February 10. He was born in 1898 in Augsburg, Germany, and died in Berlin, German Democratic Republic, in 1956.)

(This article is written in commemoration of Bertolt Brecht’s 108th birth anniversary, which falls on February 10. He was born in 1898 in Augsburg, Germany, and died in Berlin, German Democratic Republic, in 1956.)

Brecht wrote 30 long plays and eight one-act plays during a life span of 58 years (1918-1956) . Almost all these plays were directed by himself.

This practical work and the experiments associated with them led him to lay the foundation for several revolutionary theories in drama and a new system of aesthetics in general.

As Professor Marvin Carlson states (in his monumental work Theories of Theatre,Cornell University Press, 1993, 382): “No other twentieth-century writer has influenced the theatre both as dramatist and theorist as profoundly as Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), whose central concern was the theatre’s social and political concern.”

Even though Brecht has secured the place as the most important dramatist of the last century, misunderstandings still prevail regarding the purpose and content of his plays, and the dramaturgy he developed.

One of these finds some people seeing him as a politically committed artiste who only wanted to make the stage a place of instruction using the method of “alienation,” which rejects emotions.

When they observe that Brecht’s plays are not just ‘didactic,’ but on many occasions even intensify the emotions of the spectator, they seem to conclude that his plays “betray” his own theory.

Brecht wrote and directed six plays (such as The Mother, based on Gorky’s novel of the same title) that he termed Lehrstücke or didactic plays.

According to Brecht, the “learning” obtained via these plays was intended not only for the audience but for the performers as well.

Brecht was also aware of the limits of transforming the stage into a place of instruction, and he argued against attempts to use the stage as a political platform, as suggested by, for example, Erwin Piscator.

Mainly as a response to these ‘misunderstandings’ regarding his practical and theoretical work, Brecht declared in 1949: “Let us therefore cause general dismay by revoking our decision to emigrate from the realm of merely enjoyable, and even more general dismay by announcing our decision to take up lodging there.

Let us treat the theatre as a place of entertainment, as is proper in an aesthetic discussion, and try to discover which type of entertainment that suits us best” (quoted in John Willett, ed., Brecht on Theatre, Toronto: McGraw-Hill Rysern Ltd., 1975, 180).

Brecht decided that the “type of entertainment” that suits children of the current scientific era is one based on the uncovering of contradictions – the changeable nature of society and the necessity to change it.

This new type of entertainment – which he tried to provide through such plays as Life of Galileo, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, The Good Woman of Sezuan, Mother Courage and Her Children and Mr. Puntila and His Servant Matti – made him unique, even in the theatre landscape of the 21st century.

It is a well-known fact that Brecht wanted the spectator of his plays to have a critical attitude, and he experimented in his plays to generate a situation conducive to such an attitude.

However, what he meant by this attitude was not a rejection of emotions, as many critics – such as Martin Esslin (whose writings are very popular among Brecht researchers in Sri Lanka) – seemed to have thought. Brecht only rejects the generation of emotions through identification, which makes the spectator incapable of a critical attitude.

Brecht explained his position regarding this problem: “The rejection of identification does not come from a rejection of emotions and does not lead to such a situation.

It is actually a duty of the non-Aristotelian drama to prove that the thesis of vulgar aesthetics that emotions could only be generated through identification is false” (in Bertolt Brecht Schriften zum Theater, Aufbau Publishers, 1964, 26).

Brecht not only never rejected the potential of the Aristotelian theatre to generate emotions, but also made use of this potential in some of his plays; an example is The Rifles of Senora Carrar, where he preferred an unquestioning and immediate agitation to a critical attitude from the spectator engaged in a struggle against a fascist dictatorship.

In addition, Brecht never insisted that the dramaturgy he developed, which he called “non-Aristotelian,” was the most suitable one to present the contemporary world.

As is well known, he was also interested in experimenting with the new methods of presentation developed by the Theatre of the Absurd for the purpose of ‘modernizing the Socialist Theatre,’ and during the last months of his life was trying to stage Waiting for Godot by Becket. In short, he had his own ideas but was never a dogmatist.

(Dr. Michael Fernando is the former head of the Department of Fine Arts, University of Peradeniya, 2000-2008. He did his Ph.D. at Humboldt University in Berlin.

His thesis was published under the title “Brecht on the Sri Lankan Stage” by the Brecht Centre in Berlin. Dr. Fernando is also a Fulbright Senior Research Scholar.)