Sunday Times 2

‘Handle mega city projects with care’

- UN human development expert urges caution on urbanisation

- Says Lanka is a developed nation in human development category

A senior economist this week urged caution when building megacities saying it causes concentration of services and economic activity in the city to the disadvantage of rural communities.

“From a number of mega cities that I have seen around the world, I want to highlight a few issues,” said Selim Jahan, Director of the UNDP’s Human Development Report Office in New York. “When you have a mega city, in many cases it has been found that most services and economic activities are concentrated there. As a result, decentralised services or decentralised activities that should be the case in the country are not there.”

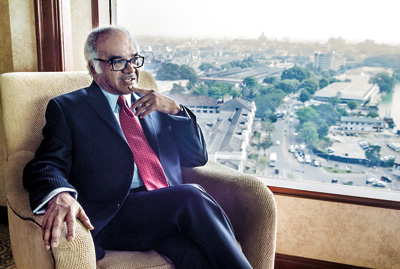

United Nations Human Development Index project director Selim Jahan speaks to the Sunday Times in his hotel room overlooking the City of Colombo, which will soon be transformed into a megapolis under a multibillion dollar project to be launched next week. Pic by Dilantha Dissanayake

“If services and economic activities are centralised, everybody will have to come to the cities to access them,” he said, in an interview with the Sunday Times. “At the same time, it may so happen that you are depriving the economic potential of places outside of these mega cities. That is unbalanced development.”

Dr. Jahan also said there was a tendency for large slums or shanty towns to develop in mega cities. “I have seen it in other cities,” he remarked. These are issues Sri Lankans will have to discuss, he said.

“I can just bring what I have seen in other places,” he continued. “Some of my colleagues and I always have a discussion. They say that urbanisation is absolutely necessary for economic development. I simply differ. Urbanisation is not absolutely necessary. Even in Sri Lanka, if you look at contribution of agriculture to Gross Domestic Product, that has gone down quite rapidly. But if you look at where people are mostly employed, that is still in agriculture. Thirty per cent of your labour force is in agriculture.”

Urbanisation is not the solution for improving the lives of those people, he held. The answer was to create dynamism in the rural economy. Dr Jahan was in Sri Lanka for the local launch of the 2015 Human Development Report. Sri Lanka’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2014 is 0.757. This puts the country in the high human development category, positioning it at 73 out of 188 countries and territories. Between 1980 and 2014, Sri Lanka’s HDI value rose from 0.571 to 0.757, an increase of 32.5 percent or an average annual increase of about 0.83 percent.

Sri Lanka is the only country in South Asia in the high human development category, Dr Jahan said: “As South Asians we can be proud of Sri Lanka. No other country from this particular sub region is in that category. India and Bangladesh are in the medium human development category and the rest of the South Asian countries, like Nepal, are in the low human development category.”

Over time, both the value and rank of Sri Lanka have improved. Life expectancy here is around 75 years whereas life expectancy in India and Pakistan is only 66. In Bangladesh, it’s 71. The infant mortality rate in Sri Lanka is less than 10 per 1000 live births but in India it’s still 52 per 1000 live births. In Pakistan, it’s 85. Taken together — the numbers, the position, the ranking, and the category to which the country belongs — Sri Lanka is not only doing well but “is very much en route to becoming, one day, a very high human development country”.

There are well known historical reasons for this. In the 60s and 70s Sri Lanka reached a literacy rate comparable with those in the developed world. It was a role model. The health facilities provided to Sri Lankan citizens over the years have been “great”. “I do not mean only the facilities which are city centric but also at the village level, in the rural economy,” Dr Jahan said. “I think basic human resource development has really made a difference. Sri Lanka is actually leveraging on some of those historical things. In recent times, I know that the country is also trying its best to increase its expenditure on health and education.”

“So I would attribute Sri Lanka’s success to investing in people quite heavily over the years, having a very good health and education system,” he said. “I also think that the creativity, as well as innovation, of the Sri Lankan people to do things has contributed.”

But there were areas to improve, particularly in the sphere of education. “One of the issues that I’ve been told by many experts in this country is that, in the education system, primary and secondary level you are doing very well but the tertiary is something you have to explore further,” Dr Jahan mused. “That’s not limited to Sri Lanka alone but to other countries also.”

It was important to remember that, in coming days, countries will have to compete in a globalised world. “People actually have to compete with people from other countries,” he explained. “So the nature and quality of tertiary education have to be very conducive to what is demanded. At this point in time, in many countries there is a kind of mismatch. The graduates being produced in many developing countries are not the kind of graduates that are needed by either global businesses or by expanding domestic businesses.”

There must be more graduates from science, technology, engineering and mathematics, Dr Jahan said. Tertiary education must be made more relevant to make people competitive in the rest of the world.

Sri Lanka is known for women’s empowerment. “But still we have constrains because, like many other developing countries, the old age population in Sri Lanka is going up because people are living longer,” Dr Jahan remarked. “I think at this moment, around 40 percent of the Sri Lankan population is above 65 years of age. In coming days, with better healthcare and nutrition, longevity will go up.”

This means there will be a “care gap” or increasing demand for care for these people. Traditionally, in every society, care responsibilities fall on women. That would mean that, in many cases, even if women choose to come out of the home and be involved in the outside work, they will be constrained by social norms, by the demand within families, to undertake the carer role which is traditionally assigned to them.

“I think there have to be debates and dialogue on how it can be overcome,” Dr Jahan said. “Do we have enough childcare provisioning in the public sector? Or do we have enough old care provisioning in the public sector? Are we investing enough there?”

Sri Lanka is also a country wherefrom a large number of women go overseas as domestic workers. They provide care to families, to children, to older people from other countries. “But in the process, and that’s true of Sri Lanka, that’s true of my own country Bangladesh, they are also leaving their own children and their old parents. So the question is who is taking care of them? It is creating a kind of a dilemma and I think there needs to be a discussion, a kind of a policy, on this as to how we can really care for the families of those workers who are earning a lot of foreign exchange for the country.”