The stage was set and a great dancer was born

Chitrasena: A vision for Kandyan dance

January 26 was the 95th birth anniversary of the pioneer Kandyan dance practitioner Chitrasena who played a pivotal role in the development of the dance in its stage form.

In this article reproduced and edited from the publication, Nritya Puja : A Tribute to Chitrasena 50 years in the dance 1936 – 1986, the author, a well known journalist, recounts the multiple impacts that Chitrasena had in bringing the dance from the ritual space onto the stage.

Jayawardhana points out some of his key achievements including the development of the Sinhala ballet and the role he played in the popularisation of Kandyan dancing, both within Sri Lanka and abroad.

Through his frequent reviews of the productions of the Chitrasena Ensemble and interactions with Chitrasena and his fellow creator-performer Vajira, the writer had keen insight into not just of the work but of some of the influences and motivations for Chitrasena’s life work.

What does eighty years of dancing mean in Sri Lanka? With a rich and variegated tradition stretching back to several hundreds, if not to over a two thousand years, with a tradition of such antiquity within which whole communities passed down an uncontaminated art from generation to generation, there must have lived many a master of the dance who could look back to his eightieth year of dancing with pride and retrace his rhythmic steps with immense satisfaction to the first day when he stood at the “dandikanda” (barre) as a little lad and decided to be a Guru some day.

To any dancer, eighty years is a remarkable achievement, an occasion for celebration. To the dancer in Sri Lanka, it is even more — a test of exceptional loyalty and dedication to his art, a trial of unrelenting perseverance in the face of poverty and social scorn, a great triumph over the severest odds, a tremendous personal victory.

But with Chitrasena, eighty of dancing years is something positively and intensely more significant, more important. Undoubtedly for him too, the completion of this long period carries a sense of personal achievement, bringing memories of struggle and triumph, of quest and conquest, of bitter and happy days, of lean and prosperous years.

But these achievements and triumphs are now no more individual and personal. Here, at the end of these eighty years, Chitrasena emerges in our retrospective vision, an important artist in an important epoch — whose eighty years are now become an indelible part of a country’s cultural history; whose personal achievements are now inseparable elements in a nation’s aesthetic and emotional life.

His triumphs have so much composed our present, that his failures too must now be reckoned as inalienable from our national destiny. If ever we as a nation, have the capacity to evaluate our own artists, we have now come to a stage,… or rather, Chitrasena has brought us to a stage, when we shall have to speak of his successes and defeats as ours.

It was indeed in the middle of an important epoch that Chitrasena emerged, as yet another market of that age in which we live. The Anagarika Dharmapala had fulfilled his spiritual mission and the first fruits of his life’s work were only being harvested.

Ananda Coomaraswamy was rediscovering the indigenous arts and had already addressed his celebrated Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs. In India, Tagore had established his Santiniketan.

His lectures on his visit to Sri Lanka, in 1934 had inspired a revolutionary change in the outlook of many an educated man and woman. The Poet-Sage of re-awakened India had stressed the need for a people to discover their own culture to be able to assimilate fruitfully the best of other cultures.

Chitrasena was a schoolboy then, and the house of his father, Seebert Dias, a well-known actor of the day, had become a veritable cultural centre, in and out of which went the literary and artistic intelligentsia of the time.

Seebert Dias, whose acting as Shylock had captivated the English-speaking audiences, now produced the first Sinhala ballet, “Sirisanghabo”, ‘presented in Kandyan technique’, Chitrasena played the lead role, and people were talking of the boy’s talents.

Some years before Anna Pavlova had visited India and taken away Udaya Shankar to Europe where his performances were making a name for all Oriental dancing.

Menaka and her Kathak performances and Ram Gopal’s Bharata Natyam were acquiring international fame. Some of these famous Indian exponents of the dance had already visited Sri Lanka.

In Sri Lanka’s upper layers, the parlour-piano and musical Victoriana were being abandoned in favour of Kandyan dancing, the sitar and the esraj. A new elite was rising which was turning a self-conscious, if sentimental eye, towards the indigenous arts.

While there was a fair amount of romanticism and ostentation in all this, the trend was not altogether without authenticity and conviction, and it was as the movement was gathering momentum that a right intuition sent Chandralekha the wife of the artist DJA, and Chitrasena to study Indian dancing under the traditional Indian gurus.

Their first choice was the “Chitrodaya” School of Travancore where they were to study Kathakali, the dance drama of Kerala, under the celebrated guru Gopinath who later, at the completion of Chitrasena’s training said of him in that typical prophetic style of the Oriental guru: “He will soon become a great dancer, having no rival in the art”.

Despite this trend the major tide of colonial civilisation flowed unabated. A slavishly-imitative elite, half-baked in European manners and victims of the West’s post-industrial commercial culture, still ruled the roost and set the pace, inciting among the nationalist elite a cultural chauvinism equally virulent.

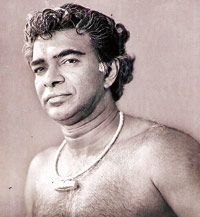

Triumphant: Chitrasena in the ballet Karadiya

Meanwhile in the villages, the traditional masters of the dance held tenaciously to their art in a desperate struggle to preserve it for posterity. But with democratic institutions had come social mobility.

Their sons, lured by the glitter and gold of the cities were exercising their new-found freedom and abandoning the hereditary art for the more secure jobs of peons and porters.

They were being realistic. They were right. The Sinhala dance was fighting a losing battle in the villages, among the common folk. The old social structures which sustained it had given way.

The aristocracy had now shifted their interests to the Bridge—table of the Planters’ Club. Before the advance of modern medicine, the exorcist ritual was dying a natural death.

Thus the less enterprising of the dancer’s sons inherited his father’s profession only to ensure for the art a mediocre existence. Purity of the dance was secured only through stagnation masquerading as Tradition.

Incompetence and dilettantism ensured their own survival by vulgarisation whose nadir was reached a few decades ago in the Kandyan Cha-Cha. There was no doubt, patriotism and a pittance could not rescue the Sinhala dance from a sure and gradual death.

It was in this context that Chitrasena returned with his training from India. Like any other contemporary artiste of Sri Lanka, Chitrasena stood where the road he travelled on seemed to fork out in two directions — the Path of Traditionalism stood counterpoised with that of Innovation, Conformity with Rebellion.

Nationalism with Internationalism, Universality with Particularity. In his own field, Chitrasena stood where Martin Wickramasinghe stood in the Novel, Keyt in Painting, Sarachchandra in Drama, Lester James Peries in the film, Amaradeva in music.

Chitrasena too accepted the challenge. The art must grow if it was to be saved from extinction. Thus Chitrasena brought dynamism to the tradition of the dance in Sri Lanka.

And he had the deftness of touch, and the awareness of the problems to conduct that delicate surgery which could effect a synthesis of tradition and modernity without sacrilegious result to the art.

In this lies the difference and the significance of Chitrasena, that while the traditional masters sought to ensure the continuance of the dance by a conservative preservation of ancient tradition — Chitrasena seeks its perpetuity by creation and innovation whereby the hidden beauties of the ageless forms can be revealed to modern men.

Perhaps he feels it is the turn of the elite to assimilate the dance from the common folk and to sophisticate it before it could go back to the masses of the future.

The limitations of the pure dance was apparently the reason for his attempt to create a genuine Sinhala ballet. For, I remember Chitrasena once told me, Tradition was a kaleidoscope within which a vast variety of forms could be created.

But the possible forms were not endless. Throughout the journey from Vidura and Ravana dance – dramas to the ballets Nala Damayanti and Karadiya, there is evident a singleness of aim — the development and extension of Sinhala dance forms, the quest for the possibilities of emotional expression within the existent idioms. And when they fail, the expansion of the national vocabulary through nature’s instinctive gestures and movements.

The absence of conventional mudras, Chitrasena once said, is not essentially a weakness in our traditional forms, inhibiting their use in ballet. It is often their strength, allowing flexibility and the use of natural gesture which is the language of the instinctive understanding.

But Chitrasena insists on the importance of expression in the arts and the artist’s right to freedom from technique. He does not conceive ‘this is traditional, this is indigenous’ as he creates.

His purpose is expression and the right technique evolves itself. “There is always a struggle between technique and artistry”, he says, “when you let go the one, you uphold the other”. This is what saves him from cultural purism.

It is what makes him a contemporary of ours instead of an antiquarian restoring museum pieces from the feudal history of the dance. He once read out to me a passage from the Kalama Sutta: “This is my attitude to authority”, he said. “This is exactly what I’ve been trying to do in the dance.”

Chitrasena is also a Universalist, an Internationalist with a difference. Although he is not restricted by cultural purism, he has always been more concerned to enrich the universal language of the dance with words from the vocabulary of the Sinhala dance than to be quick in borrowing.

Thus he has become an unofficial cultural ambassador in many lands from Perth to Moscow, Montreal to Malaysia, winning for us the hearts of the ordinary people of many nationalities.

A stroke of national good fortune seems to have saved him from being exiled in an embassy abroad or imprisoned in a beaucratic cubicle, during this last seven years. Chitrasena instead has lived a free man and active.

It is how he brought before the public his latest production which was conceived shortly after Karadiya. “Kinkini Kolama” he says, “is an extension of the work I have been doing all these years.”

Eighty years of Chitrasena has also had its meaning for the rest of the art-world. There has hardly been a name in the world of arts and letters which has not at one time or another been associated with the Chitrasena Dance School — inalienable among them, Somabandu, the costumes and decor artist.

And recently, Lester James Peries wrote, “a friend of mine who is among the leading authorities on music in this country and whose opinion I respect is pretty certain the score for Karadiya, the Chitrasena ballet, is the greatest score ever written in this country.” Amaradeva’s early days are closely linked with the Chitrasena School.

But there is one more of Chitrasena’s contributions to the art of the dance in our country which is unique and second to none — the creation of Vajira.

There is not a single peak of achievement reached by Chitrasena in these eighty years but in the attaining of which his pupil, this dancer of compelling grace and perfect technique, does not hold her share.

Whether in the romantic fantasy that was Nala Damayanthi where she sketched in as fine a line as Keyt’s, that celestial swan, or in the stark realism of Karadiya, Vajira remains distinguished, with her assurance of step and certainty of balance, her acute sense of rhythm responding to the subtlest nuances of music, the natural gift of her lithe pliant figure adding the quality of lasya to the most vigorous and virile of Kandyan Vannams. Out of the wings of Chitrasena’s Studio, Vajira emerged vibrant like Degas’ “Dancer on the Stage.”

At their studio in Kollupitiya — by the strange ironies of history, the last Sanctuary of the Sinhala dance fast languishing in the villages of its birth — I saw them dance some years ago — Chitrasena and Vajira.

It was merely an evening’s exercise with their pupils, and the glow of the setting sun was on their faces. But they danced with the seriousness of a gala-performance. “We give you”, said Chitrasena, ‘something that is very traditional and something that at the same time is not.”

As the dance rose in crescendo to a frenzied climax, with an equally frantic drum, Chitrasena paused for a moment and said, “This is discipline.

You can’t do this without thinking.” And as they danced, I was reminded of the beautiful phrase with which the late Mr. Reggie Perera defined the unity of the tandava and lasya modes.

“It is the marriage of supple sinewy steel and the sinuous grace of gossamer silk.” There is no finer phrase by which we could describe Chitrasena and Vajira joined in the dance, for, perhaps (to use the words of an ancient Indian critic) they dance not for men but to feast the eyes of the gods.