Simplicity in life and art

View(s):Most artists crave success and recognition as they strive to make their mark on the world, but not so for the Sri Lankan artist Richard Gabriel who died this month in Melbourne, Australia. Gabriel was indifferent to fame and lived a life largely detached from materialism. He believed his life was guided by divine providence and throughout his long career which stretched over 75 years, he avoided publicity, never had a regular dealer, and disliked those who bought his art to speculate on it for profit.

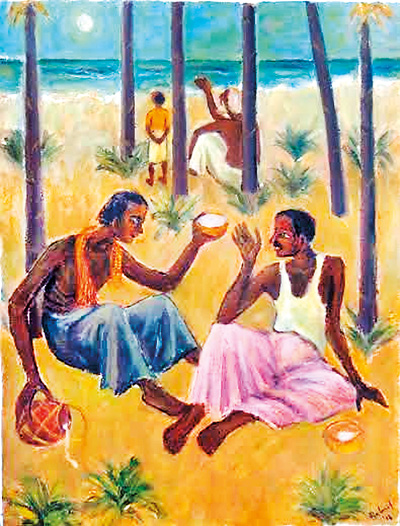

Moonshine: One of his last paintings inspired by the memory of a beach in Batticaloa

Born in Matara on February 19, 1924, Richard was educated at St. Mary’s Convent, Matara, and St. Peter’s College, Colombo. From an early age he drew and made models of houses and warships. He liked to watch his mother making pillow-lace and doing crochet work and she was happy to see Richard painting.

In early 1941, his elder brother Edmund, who knew the Peries brothers (Lester and Ivan) from schooldays, introduced Richard to Ivan, who was an established artist. For the next year Richard went to Ivan’s home each week to learn about art which consisted mainly of talks about the history and philosophy of art. When Ivan had nothing more to tell him, he arranged for Richard to meet the painter and teacher Harry Pieris who had taught at Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan in the 1930s.

In an oral history recorded in 2013, Richard described his first meeting with Harry Pieris like this,

‘I first met Harry in his home in Rosmead Place, Colombo 7. It was in the early days of World War 2. His servant opened the door. He was dressed in white and took me upstairs. I was terrified to be in this big house full of lovely antiques, books and art. I was shown into a room and Harry was seated with a book. He spoke softly. He was from a wealthy family but he immediately accepted me without barriers. I showed him a painting I did of an old beggar. After looking at it, he advised me to come back and see him after I had finished my exams. It was the beginning of a lifelong master-pupil relationship.’

Gabriel’s entry into the art world began after his work was exhibited at the War Effort Exhibition in Colombo. One of the works was a pastel of a church with people looking up into the sky. The drawing captured a moment on 5 April 1942, Easter Sunday, the day Japan launched an air assault on Colombo. Richard had been attending mass at a church in Dehiwela when the attack started. He came out to see what was going on and the experience of seeing people looking up at the dogfights compelled him to draw it.

The next year Richard joined the ’43 Group. His entry into the group came through Lionel Wendt who had seen a Gabriel oil painting at Ivan’s home. The work depicted students digging the ground to plant manioc and sweet potatoes which Richard had painted in WW2 when there was a fear of food shortages. Wendt liked the painting and told Ivan, ‘That’s a nice picture.’

‘It is upside down.’

‘Well, if it is right side up it should be better. Why not get him into the group too?’

‘He’s still studying.’

‘That doesn’t matter.’

As a founding member of the ‘43 Group, Richard came to know the leading artists of the day including Lionel Wendt, Justin Daraniyagala, George Claessen, George Keyt, Aubrey Collette and Geoffrey Beling, but he never forgot Ivan and Harry who did so much for him. He came to regard Harry as a foster-father.

The ‘43 Group did not have a manifesto except for 14 words recorded in the minutes of the inaugural meeting, held at Wendt’s home on 29 August 1943 which read, ‘Group exists for the furtherance in every way of art in all its branches.’ The spirit of these few words gave artists freedom and control over their art. Each artist was also free to select their own works for group shows. This suited Richard who found himself in the right group among the best artists, which he also attributed to divine providence.

Another influential person in his life was Fr. Peter Pillai OMI. Richard knew him as a student at St Peter’s College. In 1945, Fr. Pillai invited Richard to teach art at St Joseph’s College. He had made drawings of Fr. Pillai as a student, but the opportunity came to make a beautiful wood carving of Fr. Pillai.

As Richard remembers, ‘One day a student gave me a block of wood. The look and feel of the wood reminded me of Fr. Pillai’s forehead and it inspired me to carve his head.’ With his intellectual passion and devotion to the church, Richard also came to regard Fr. Pillai as a divine providence in his life and art.

In 1952, having received a grant from the British Council, Richard went to London to study at the Chelsea Art School. However, after a tiff with his teacher, Mr. Scoff, he left the school to study with the French painter Peter de Francia who gave him constructive suggestions and taught him techniques practised by Marc Chagall and other artists in France for preparing a canvas to preserve and extend the life of a painting.

Richard Gabriel: Portrait in July 2014

Richard’s paintings were exhibited in the ’43 Group shows organised by Ranjit Fernando in the UK, France and at the Venice Biennales in the 1950s. The ’43 Group held exhibitions at the Imperial Institute in South Kensington in late 1952, the Petit Palais in Paris in 1953, the Beaux Arts Gallery, and the Heffer Gallery in Cambridge in 1954.

After his studies in the UK, Richard returned to Sri Lanka to work as an artist. He held an exhibition at the Italian Embassy in Colombo in 1967, which was organized by the Italian Ambassador, Edoardo Costa Sanseverino di Bisignano. The following year he exhibited his paintings at the Mostra Internationale della Grafia in Florence. In 1980 he joined the Smithsonian Institute travelling exhibition which was sponsored by the New Orleans Museum of Art. In Sri Lanka, his work was frequently exhibited at the Lionel Wendt Gallery and the Sapumal Foundation.

The influence and legacy of the ’43 Group is indelible and far-reaching. In a talk given in Colombo at an exhibition of paintings by Neville Weereratne and Sybil Keyt, the film director and screenwriter Lester James Peries, described it as ‘more than a revolutionary movement…it was in the words of the poet W. H. Auden… a climate of opinion [which] changed for us and for generations to come our perception of the landscapes, the seascapes and the people of our island home.’

Gabriel was an important part of this climate and change. Never one to get caught up in passing fads or the trends and fashions of intellectualism in art, his journey was much more internal and personal. As with his contemporaries in the ’43 Group, he was attracted to the environment in Sri Lanka, particularly its rural life, fishing communities and animals, but also the human experience. Influences of Western art traditions were not strong or obvious in his work.

He chose to study humans in everyday situations. A family quarrel, a mother and child, conversations on a beach, milking a cow, resting with a bull, a monk giving advice, women gathering paddy, fishing boats, and family portraits, Gabriel captured these with intense colours, simple compositions and perspectives, and with a quiet restraint that did not impose but rather drew a viewer in. He liked to use certain hues of blue, red, brown and white in his paintings, which was related to his perception of light in Sri Lanka or to the clothing worn by men and women.

Richard had a natural attraction to the sea and fishing communities and it became an important subject in his work. This attraction came in part because he lived near the sea but also because of Biblical references connected to Jesus Christ and fishermen. He liked to integrate these elements in his paintings, though the narratives were often tied to human experiences as in ‘Solitary Fisherman’. This painting shows the shadow of a woman behind a man sitting with his head resting on his arms which raises questions about their relationship. Who is she? Why is she there? It is open to interpetation, but for Richard it was a scene of unrequited love.

In 2014, while I was with Richard in his studio, a new oil painting was on his easel. It was a painting of two men enjoying toddy while sitting on a beach in Batticaloa in the moonlight as a child and man behind them gaze up at the moon. The title of the work became ‘Moonshine’. Richard told me he had seen it while staying in Batticaloa in the 1960s. The image had lived in his mind for over fifty years before he manifested it on to canvas. The painting, which was acquired by a collector in New Zealand, has a certain hue of blue mixed with green which captures the moonlight at dusk as it reflects back on to the beach.

A prolific artist throughout his life, his output consists of paintings, wood carvings, sculptures, etchings, pastels, drawings and sketches. His art can be found in the homes of Sri Lankans all over the world but the exact number of artworks he produced is unknown. Richard did not keep records of the buyers or details of the works he produced and so the documentation of his works from the 1940s to 1980s is fragmentary. It was only after he moved to Australia in 2002 to live with his daughter Rene and son-in-law Hiran Leitan that the task of documenting his output began with meticulous and methodical care.

Richard rarely held solo exhibitions, preferring to exhibit his work in group shows. In 2014, a solo exhibition of his work was organized in Kandy by Alliance Française. The paintings exhibited were borrowed from the private collection of Shamil and Roshini Peiris.

On Good Friday 2015 Richard started his last painting. It was titled Crucifixion and it took Richard almost a year to finish it as he suffered aches and pains in his arms and legs which slowed him down. On 7 February 2016, he suffered a heart attack and was admitted to the Monash Medical Centre in Melbourne. He died 12 days later on his 92nd birthday.

Richard will be mourned by many friends, young and old, for he was not only a very fine artist, but also a compassionate and imaginative human being.

He married Sita Kulasekera in 1951. She predeceased him in August 2001. He is survived by his son Angelo Don Gabriel and daughter Rene Leitan (nee Gabriel).