The Victorian lady traveller who painted Pera

A lady an explorer? A traveller in skirts?

The notion’s just a trifle too seraphic:

Let them stay and mind the babies, or hem our ragged shirts;

But they mustn’t, can’t, and shan’t be geographic . . .

- Punch magazine, 1893

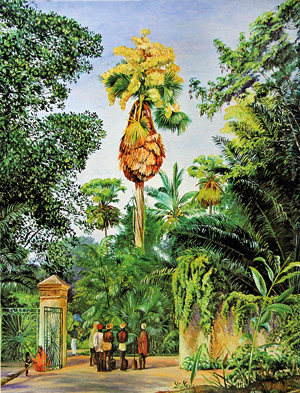

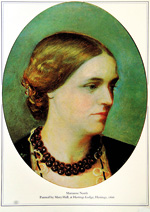

Marianne North (inset) and her detailed painting of a talipot palm in full bloom

Should you ever visit the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, on the outskirts of London, make sure to take in one of the lesser-known attractions there, the Marianne North Gallery. Situated on one of the main walkways a few hundred metres to the left of the Victoria Gate entrance, the Gallery lies comfortably between what is known as the Ruined Arch and an immense flagpole, a relic of empire, flying what else but the Union Jack.

Walk up the steps and through the imposing double doors and you will find yourself in a large, ornate and high-ceilinged hall. What hits the eye with immediate impact is the fact that every scrap of wall space below the elevated windows is covered with a colourful mosaic of hundreds of paintings devoted to botanical subjects and views incorporating flora. On closer examination, it will be found that the paintings are representative of temperate, sub-tropical and tropical regions. In fact, there are over 800 of them featuring a score of countries.

The person who executed these paintings was the Marianne North of the Gallery name. North was one of the most exceptional women of the Victorian era. As if her tremendous contribution to botanical study was not enough, the travels North had to make in order to execute her paintings were extensive and in some instances, pioneering. In addition, therefore, she also belongs to a small band of Englishwomen who, when the movement for women’s emancipation was gathering momentum, became known for their journeys around the world.

Dorothy Middleton has encapsulated the common factors, impulses and philosophy that unite these women in Victorian Lady Travellers (London, 1965). “From about 1870 onwards,” she wrote, “more women than ever before or perhaps since undertook journeys to remote and savage countries; travelling as individuals, and for a variety of reasons, they were mostly middle-aged and often in poor health, their moral and intellectual standards were extremely high and they left behind them a formidable array of travel books. Nearly always they went alone, blazing no trail and setting no fashion.”

“Though this outburst of female energy is undoubtedly linked with the increasingly vigorous movement for women’s political and social emancipation, it was neither an imitation nor a development of the male fashion for exploration which was such a feature of Victorian times. Whereas the famous lone travellers among the men were followed up by expeditions of ever-greater size and complexity, the women did not inspire such an outcome. The camaraderie of the camp, so nostalgically enjoyed by the Polar explorer and the mountaineer, was not what the women were after . . . On the whole discovery has not been a woman’s province.”

North largely conforms to Middleton’s conception of the Victorian lady traveller, or “globe-trotteress” as she termed the phenomenon. Born in 1830, North came from an upper middle-class family. Her father was the Liberal Member of Parliament for Hastings, a man who enjoyed a wide acquaintance among the scientific, artistic and political personalities of the day.

North largely conforms to Middleton’s conception of the Victorian lady traveller, or “globe-trotteress” as she termed the phenomenon. Born in 1830, North came from an upper middle-class family. Her father was the Liberal Member of Parliament for Hastings, a man who enjoyed a wide acquaintance among the scientific, artistic and political personalities of the day.

North revealed an inclination for travel and a talent for graphic representation at an early age. After the death of her mother in 1855, she travelled widely in Europe with her father, and beyond to Turkey, Syria, and Egypt. On the death of her father in 1869, North lost the one strong emotional attachment of her life. At the age of 39, unmarried and free from the burden of family, she decided to devote the rest of her life to travel and painting.

In 1871, North began the first of her many journeys, visiting the United States, Canada, and Jamaica. She returned to England for a brief period, before setting off for Brazil. In 1875, she crossed the North American continent on her way to Japan, returning home in 1877 via Sarawak, Java, and Ceylon.

North sailed from Singapore to Galle in late 1876 and checked into the Oriental Hotel on arrival. North wrote that the hotel was “famous all over the world. Mrs Barker, the landlady, made me most comfortable, sending all my meals into the room, and I fixed on a driver I liked, and had him every morning to drive me out.”

She provided detailed documentation of her journeys in the three volumes of her sometimes tedious autobiography, Recollections of a Happy Life, 2 Vols. (London, 1892). The subsequent Further Recollections of a Happy Life (London, 1893) contains material edited out of Volumes 1 and 2.

Though telling us much of where she went and of how she got there, North says very little about her methods of work and often demonstrates little comprehension of social issues. So it was that she wrote of the recent emancipation of slaves in Brazil: “It would have been better perhaps if our former law-makers had not been in such a hurry, and so much led away by the absurd idea of ‘a man and a brother.’”

Though telling us much of where she went and of how she got there, North says very little about her methods of work and often demonstrates little comprehension of social issues. So it was that she wrote of the recent emancipation of slaves in Brazil: “It would have been better perhaps if our former law-makers had not been in such a hurry, and so much led away by the absurd idea of ‘a man and a brother.’”

Much of her writing on Ceylon betrays the unfamiliarity and heightened exoticism of a griffin, or newcomer to the East. This, for instance, caused her to confess: “I do not think I knew what coconuts were till I saw those of Ceylon. There they are the weed of weeds and grow on the actual sea-sand.” Then again: “The sand was most golden, and the tropical crabs ran over it like express trains. There were also lovely rocks of rich and golden tints scattered about in front of the sea, and the edge of the sand was bordered with the beautiful sea-grape, with masses of pandanus on their stilted roots.”

Eight days were spent in Galle, during which time North completed several paintings. Although she received little formal training and was somewhat unconventional in her technique, her work achieved a high standard of artistic competence. She painted quickly, often completing a picture in a single day. Her paintings varied in size, from several square centimetres, to about one metre by 38 centimetres. Apart from the flora for which she is best known, birds, insects and other animals feature in many of her paintings. Some are pure landscapes, such as the ones of Galle.

North took the horse-drawn coach that connected the port to the capital, Colombo. She made use of the “bigwigs” in virtually every country she visited. Ceylon was no exception. Out-of-the-ordinary travellers invariably sent a letter to the Governor informing him of their arrival on the island. This is precisely what North did, so that when she reached Colombo, Sir William Gregory offered her “all kinds of hospitality”. However, she was anxious to leave for Kandy.

When she arrived, her first excursion was to the nearby Royal Botanic Gardens, Peradeniya, to meet its renowned and long-serving director, Dr GHK Thwaites. “He had planted half the trees himself, and had seldom been out of it for forty years, steadily refusing to cut vistas, or make riband-borders and other inventions of the modern gardener,” she remarked. “The trees were massed together most picturesquely, with creepers growing over them on a natural and enchanting tangle.”

The venerable Dr Thwaites made a good impression on North, for she declared: “He was one of the most perfect gentlemen I have ever known, and I longed to be able to stay a while to rest and paint near him and his beautiful garden.” This she was able to do, as the Governor had given her a letter of introduction to a certain ‘Judge L,’ who lived opposite the Gardens, and he insisted that she take up quarters in his spare rooms.

“It was the very nest I had been longing for,” North admitted. “From my window, I could see a thick-stemmed bush of the golden-leaved croton, and many pink dracenas, while under them were white roses as lovely as any at home. Then came the lawn, and a great Jak-tree with its huge fruit hanging directly from the trunk, and branches with shining leaves like those of the magnolia. A coconut was beside it – a delicious contrast with its feathery head, masses of gold-brown fruit, and ivory flowers, like gigantic egret plumes.”

But it was the Botanic Gardens that held the greatest fascination for the painter. “There was a noble avenue of India rubber trees at the entrance to the great gardens, with their long, tangled roots creeping over the outside of the ground, and huge supports growing down into it from their heavy branches. Every way I looked at these trees they are magnificent.”

It was not only this avenue of rubber trees that North so effectively captured on canvas at the Peradeniya Gardens. She also had the rare opportunity of painting a talipot palm in full bloom. This extraordinary species flowers just once, producing a massive inflorescence, and after fruiting, dies. North’s painting of this palm is surely one of her finest.

“I settled myself to make a study of it,” she wrote, and then went on to explain the curious figures in the painting that can be discerned near the gate, holding strange implements. These apparently were ‘loaded clubs’, and the men were grinding down the stones in the roadway while they sang a monotonous chant, at the end of each verse lifting up their clubs and letting them fall with a thud.”

While she was at Peradeniya, North was invited to dine with the Governor at his residence in Kandy, known as the Pavilion. She spent the night as well, accommodated in the huge staterooms last occupied by the Prince of Wales the previous year, 1875. “His Excellency showed me in, and looked himself to see if they had put sheets on the bed, for nobody was there to be responsible but the gardener. I felt like a sparrow who had by mistake got into an eagle’s nest.”

After travelling back to Colombo with the Governor, North proceeded to Kalutara, where she had been invited to stay by Julia Margaret Cameron. How appropriate that one notable woman of the Victorian era should meet up with another in Ceylon. Cameron was one of the very first portrait photographers and had pioneered several techniques, such as soft focus and harsh lighting, which heightened the expressiveness of portraits. She took up photography only in 1863, at the age of 48, yet within a decade she had become a central figure in this new medium and had photographed many great figures of her time. North’s encounter with Cameron justifies a separate article.

On January 21, 1877, North took the night coach south to Galle and sailed to Europe. However, by November 15 the same year she was back in Ceylon, en route to India, and travelled to Peradeniya especially to see her friend Dr Thwaites.

In a review of an exhibition of North’s paintings held at a London gallery in 1879, it was suggested that her work be housed at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. North took up the idea and received permission to build a gallery for the paintings within the gardens at her own expense. While it was being built, North resumed her travels – this time to Australia and New Zealand – at the behest of Charles Darwin.

On her return, she spent a year arranging the paintings, continent by continent, in painstaking, jigsaw fashion. The unconventional nature of her accomplishment, and the gender-based passions it aroused, is illustrated by an incident that took place while North was completing the arrangement. The door of the Gallery was accidentally left open, and a man entered: “He turned rather rudely to me, after getting interested in the paintings – ‘It isn’t true what they say about all these being painted by one woman, is it?’ I said simply that I had done them all; on which he seized me by both hands and said, ‘You! Then it is lucky for you that you did not live 200 years ago, or you would have been burnt for a witch.’”

Soon after the opening of the Gallery in June 1882, she travelled to South Africa. A year later she went to the Seychelles and, in 1884, despite ill health, to her last destination, Chile. The paintings executed on these journeys were added to the Marianne North Gallery at Kew, which today houses 832 of them. Although many of these are views, in total no less than 727 genera and approaching 1,000 species are portrayed. Sixteen of these paintings are of Ceylon, five of which feature the Royal Botanic Gardens at Peradeniya.

Marianne North died at the age of 60 on August 30, 1890. Her contribution to botany can be judged by the many plants that were barely known before she painted them. In fact some were unknown, for her name has been given to five – four of which were first figured and brought to European notice by her. In addition, over the past 120 years, millions of visitors to Kew have looked and marvelled at her gigantic botanical stamp album.