Pearls for a President

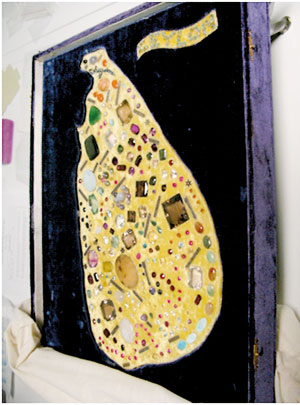

A diplomatic gift: A map of Ceylon (above) handcrafted by Abdul Wahab that was presented by Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike to US President Dwight D Eisenhower at the Whie House (below)

The mystery surrounding the living gem of the sea, the pearl, has long captured the interest of merchants, the imagination of poets and attention of historians. The existing fragmented narrative surrounding the once thriving cultures of diving, harvesting and trans-oceanic distribution of natural Mannar pearls is a rich part of Sri Lanka’s diplomatic, commercial and cultural histories. The story of the Mannar Pearl is one entrenched in cultural and diplomatic dialogues across time and space from ancient China to 20th century America.

Of the 3,600 marine species the Gulf of Mannar is home to, the celebrated ‘Pearl Oysters’ of Sri Lanka are known to be found mainly in certain parts of the wide shallow plateau of the upper end of the Gulf of Mannar upto Chilaw. Mannar lies off the north-western coast of Sri Lanka to the south of Adam’s Bridge. It is probable that a pearl bank could once have existed in Mount Lavinia. Pearl banks also exist on the opposite coast of India.

The pearl fisheries of India, Sri Lanka and the Persian Gulf have been historically known to yield the highly prized ‘Oriental Pearl’ and are probably the most ancient fisheries till their relatively recent staggered decline. A striking feature of early 20th century British records of pearl fishing in Sri Lanka is that the systems of fishery carried out in the 1900s were under very much the same conditions as 2-3000 years ago.

The Gem of the Moon and Sea

The natural pearl is a product of a living body. The oyster from which the pearl is produced inhabits the sea as its natural habitat. The oyster coats granules of sand or other foreign bodies which may enter its shell causing irritation with layers of Calcium Carbonate. In comparisons drawn between the lustre of good pearls and moonlight, pearls have been identified as the essence of the moon. An ancient theory from the Orient suggests that pearls were conceived by the penetration of moonbeams into the open bivalves of the oyster.

A golden map of Ceylon

My grandfather, the late Abdul Wahab, founder of Bullion Exchange Jewellers was an earnest collector of pearls. As related by his sons, the present partners of Bullion Exchange Jewellers, their father would carry sacksful of Mannar Pearls to Colombo in the trunk of his Hillman in the early 1960s. Each sack containing 600-700 oysters would be shelled in the compound of Bullion Exchange Jewellers in Bambalapitiya, just as cashew would be shelled in homes elsewhere. This process was very much a part of a home industry conducted within jewellery establishments in the mid 20th century.

In 1956, on the personal request of the fourth Prime Minister of independent Ceylon, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, Bullion Exchange Jewellers produced a golden hand crafted bejewelled map of Ceylon to be presented by the Prime Minister as a diplomatic gift to President Eisenhower at the White House. This map had set on it among others, five Mannar pearls showcasing three extremely rare pink Mannar pearls. The golden map is currently preserved at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Texas.

The Ceylon Daily News on October 31, 1956 reported it thus:

“A map of Ceylon studded with all precious stones will be presented by the Prime Minister, Mr. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike to President Eisenhower when he visits the U.S.A…This gift was completely designed and manufactured at Bullion Exchange. The Gems were selected from the private collection of Mr. M.A. Wahab, the firm’s Managing Director. The inner gem box is decorated with Buddhist Motifs and mounted on ebony elephants…”

The rare collection of Mannar Pearl jewels preserved at Bullion Exchange Jewellers include antique jewels produced by Punchi Singho & Bro. Jewellers of Colombo for the Gold Medal Wembley Exhibition in London in 1924 and an exquisite Mannar Pearl and cabochon Blue Sapphire set featuring 380 handpicked natural Mannar Pearls from 1860. Of the most precious of my grandfather’s pearl collection was a perfectly shaped twin pearl which is a rarity to the extent of one to every 10,000 pearls shelled. A symbol of love and luck, this pearl was gifted to my grandmother and the family heirloom remains a part of the collection of the jewellers.

Pearling networks of the past

From ancient history into the early 20th century, the ports surrounding the pearl banks of Mannar have been an entrepôt for traders, sailors, saints and merchant capitalists traversing the high seas from Europe and West Asia to the Far East and vice versa through Sri Lanka, the pearl on the Indian Ocean. While pearls are not usually a characteristic symbol of monetary wealth, they are of high symbolic significance owing to their putative powers, talismanic qualities and mysterious nature.

Gaining repute through traditional trading routes of old such as the Silk Road of the sea reaching kingdoms from Persia to Rome in the West and Peking in the East, pearls have been included in payments of tribute, rewards to successful generals and offered as presents cementing diplomatic friendships and marriage alliances. The natural pearls produced in the pearl banks of Mannar were bartered through extensive trade networks. Internationally, pearls from the Persian Gulf, Southern Arabian waters and the Sri Lankan side of the Mannar pearl banks were of equally high value and repute through ancient and medieval kingdoms across the world.

Venetian traveller Marco Polo who visited the Gulf of Mannar in 1294 relates the interconnectedness of the pearling industry to charms and magic. He notes the significance of the Abraiaman understood as the Brahman and fish-charmers who were rewarded handsomely by merchants for ‘charming’ big fish surrounding the Gulf to prevent pearl divers from being attacked by them during the perilous dive in the banks of Mabar of India, 60 miles to the west of Sri Lanka. Similarly, the shark binder played a prominent role in keeping the sharks at bay. Through the use of prayers and charms these shark binders were believed to provide safety from shark bites and death. Their charms are said to have been aimed at the sharks around the Gulf of Mannar whose jaws would be bound over the duration of the dive, thus protecting pearl divers. Without the presence of at least two shark binders on the sandy coast, divers would not take the perilous plunge for oysters.

Pearl Fishing in Sri Lanka

“Under a glaring sun, from an ocean

dotted with stout boats and bobbing black-

heads, the precious oysters are gradually piled up on the boats until about noon, when a gun

from the Government boats warns the fleet that

the time allowed for fishing has expired, and a

wild race takes place among the boats to reach

the beach first…and the beach becomes a screeching mass of

excited natives, jostling each other and shouting

in a hundred queer tongues…”

Carlo Lavi on ‘The Pearl Fishers of Ceylon’

The Wide World Magazine (1904)

Mr. Wahab and others presenting the map to Premier Bandaranaike

The Tamil name for Mannar, capturing the significance of its richness and importance to locals is ‘Salubham’ (Sea of Gain). The most famous ports of Sri Lanka in which pearls were acquired were Mantai and Arippuu. Dr. Roland Silva in the National Trust and Central Cultural Fund publication Maritime

Heritage of Lanka: Ancient ports and harbours, writes that in the field of navigation, all ships from the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf had to touch Sri Lanka on their way to the East. Thus, the north-western seaboard was an early port of call for many goods including natural Mannar pearls. Dr Silva further identifies the earliest and most accurate map of Sri Lanka being one prepared by John Davy in the early 19th century in which Arippu (known as the centre of northern fisheries) is distinctly marked as pearl fishing grounds. The pearl fishing season in Mannar according to Dr. Silva lasted for seven months of the year until the onset of the rough south-western monsoons in the month of May.

The dive was taken predominantly by Indian Tamils from Kilirarai and Arabs. Acrobats and snake charmers entertained the several thousand who gathered over this season. While the pearl harvesting festivities were underway, the potential fatal tragedies involved in harvesting the pearl always loomed.

The Decline of Pearling

The massive trading potential of natural pearls led to the successive and sustained interests by European colonial governments in dominating the pearling industry of Mannar and Ceylon. Rohan Pethiyagoda in Maritime Heritage of Lanka: Ancient ports and harbours estimates that in 1881 the pearl fishery of Sri Lanka grossed one million US Dollars which is the approximate value of twenty-five million US dollars in the present context. However, with such sustained interest came a level of exploitation of these precious natural pearl banks through overfishing. According to Mr. Pethiyagoda, the resource began depleting by the early 20th century citing the numbers of almost 82 million oysters being brought on shore in 1905 leading to the exhaustion of this precious gem of the sea unique to the pearl banks of Sri Lanka.