Restoring for posterity the home of a Sinhala scholar of yore

Far away from the salubrious climes of Kandawala, Katana, close to Negombo and what was his ancestral home set amidst groves of coconut palms, is a tiny plot in the arid peninsula of Jaffna all of his own.

What distinguishes him from numerous others in this final resting place in the heart of Jaffna town is not only the typical Sinhala kuluna (column) rising above the others to mark his grave but also the tribute from grateful students in all three languages.

What distinguishes him from numerous others in this final resting place in the heart of Jaffna town is not only the typical Sinhala kuluna (column) rising above the others to mark his grave but also the tribute from grateful students in all three languages.

Moss-covered and somewhat weather-beaten this grave-marker may be but it has withstood the test of time to stand tall in testimony of Mudaliyar Don Eustakius Johannes Senanayake’s contribution to his mother-tongue.

Even now, more than a century later, ‘Johannes Viyakarana’ is referred to with awe. This is what brought fame as well as a name (title) to him.

Johannes may have passed on more than a hundred years ago, but his meticulous compilation of ‘Sinhalese Grammar – For use in schools’ lives on in the minds of many and his granddaughter, Prof. Priyadarshini (Preenie) Senanayake, is urging the Director-General of Archaeology, Dr. Senarath Dissanayake, to declare his home a national monument.

His home built back in 1908 which is also more than a hundred years old is the stately ‘Senanayake Walauwwa’ at Kandawala, bordering the Negombo-Katana Road.

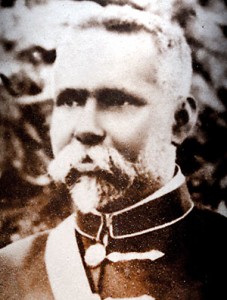

Johannes of Viyakarana fame

Contacting the descendants of Johannes’s 11 children, Priyadarshini has persuaded them to rummage through their antique almirahs and unearth sepia-toned photographs of the weddings of three of his daughters, Grace, Winifred and Beatrix. The marriages had been celebrated at the sprawling walauwwa in 1914, 1915 and 1916 respectively amidst much pomp, with the wedding parties posing in all their finery in the columned porch, “the roof trim with lace-like edging”.

By that time Johannes was no more having succumbed to a lung infection in Jaffna where he had been sent to recuperate. It is here at the largest Roman Catholic cemetery close to St. Patrick’s College that his remains have been laid to rest and marked with the kuluna as the tombstone hewn with the words: ‘In memory of Mudaliyar D.E. Johannes Senanayake, the late Head Master of the Singhalese Dept. of the Govt. Training College Colombo; by his pupils’ not just in one but all three languages of English, Sinhala and Tamil. This is a privilege accorded to him in keeping with his significant contribution and knowledge, with most others lying beside him having the final farewell only in Tamil or English.

Many would have been the Head Masters of the Sinhala Department of the Government Training College, so why a special monument for Johannes? Priyadarshini is quick to produce a copy of the Sinhala Grammar compiled by her grandfather which her own father and Johannes’s youngest son, Oswald, re-published in 1949. An earlier much-yellowed and dog-eared reprint of 1929 is preserved in the National Museum’s Library in Colombo.

This is what Johannes had written in his Preface dated 1st December 1911 to the book: “The Sinhalese Grammar called the ‘Sidatsangara’ was compiled by a learned Buddhist priest who presided over the Patiraja Pirivena, a Buddhist College, some 600 years ago. It has been taught by Sinhalese teachers to pupils with respect and devotion ever since its compilation. Although the ‘Sidatsangara’ can be highly commended for the nice arrangement of its rules (sutras) and examples, yet the language in which it is written is beyond the comprehension of beginners in grammar. I have therefore attempted in this work to provide those who are as yet not acquainted with ‘Elu’ the ancient language of Ceylon, with a grammar written in language more familiar to them.

“This book consists of all the useful and important rules given in the ‘Sidatsangara’ as well as other information essential to a knowledge of modern Sinhalese…………Any teacher can select from this book the portions of grammar for each standard as required by the Code of the Education Department, such as the classification of letters of the alphabet, the gender and number of nouns and the three tenses of verbs for the 4th standard; the full declension of nouns and pronouns, a few rules of euphony and some moods to verbs for the 5th standard; all the rules of euphony and the full conjugation of verbs for the 6th standard &c.”

Granddaughter Prof. Preenie Senanayake

Crystal clear and simple are his teaching methods, a pointer to what a good teacher of teachers should be.

“Nivaredi Sinhala viyakarana pothak nirmanaya kare Johannes,” says 86-year-old M. Norbert Costa, respectfully known as ‘Gurunnanse’ in his village of Kandawala, explaining that a scrupulously correct Sinhala grammar book was created by Johannes such a long time ago. He would know, as he is a Sinhala trained teacher with 33 long years of service minus nine as a Principal in 11 schools across the country in the districts of Colombo, Badulla and Polonnaruwa. He had used this grammar book as his guide in his long years of teaching.

Tales abound about Johannes, says Mr. Costa, how he had heard that the famous grammarian, writer and poet, Cumaratunga Munidasa, was one of his students, while for services rendered to the language, then British Governor Henry Edward McCallum bestowed him with the nambu-namaya (title) of Senanayake Guru Mudali.

Mr. Costa sketches the life of Johannes: Born on May 22, 1855, he had entered the Sinhala Section of the Teacher Training College in 1870 as a student. Clever he had been and in two years begun lecturing at the Training College, with his career taking off from there. He had been bestowed the Mudaliyar title in 1913.

His name evokes reverence from people of diverse professions – an archivist recalls how easy it was to learn the language from the “podi potha” (small book) that was the ‘Johannes Viyakarana’. His father had been a teacher and this book was amongst his most prized possessions. Yes, ‘Johannes Viyakarana’ is well-known and was the foundation on which Sinhala was taught those days, says a Sinhala professor.

Priyadarshini, meanwhile, laughingly points out that while Johannes was engaged in the national service of teaching teachers the best way to impart Sinhala to students across the country, it was his wife Elizabeth who attended to matters domestic including the building of the walauwwa.

As part of Priyadarshini’s precious possessions is a note in beautifully-rounded Sinhala letters that Johannes had sent Elizabeth on February 11, 1908, while he was at the Teachers’ Training College in Colombo, with instructions regarding rain protectors (eaves) for the windows and what building material to use on the parapet wall encompassing the large coconut estate. Another memento that is given pride of place is the well-thumbed and falling-to-pieces Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary of Johannes.

As the ‘Lady of the Manor’ presiding over 200 acres of land extending from Kandawala to Kochchikade, Elizabeth was the tough one. Adorned in white and black, with a large-beaded rosary wrapped around her wrist she would go on her rounds of the estate infested with nai and polongu (cobra and Russell’s viper) brooking no argument against her orders. Anyone who disobeyed would draw her ire and the punishment would be gahe bandinawa(being strung to a tree).

The kuluna marking Johannes’s grave

Priyadarshini’s forays into the past to piece together the life of her grandfather indicates that Johannes was originally from Pamunugama, a “depressed” area from which his father moved to Kandawala in search of greener pastures.

She recalls how their faithful housekeeper, Ano Akka, would regale her with sad tales of how Johannes’s mother died when he was little and his father re-married a woman from Kandawala and “in that bed” had three more children.

The kudammma was a wicked one who ill-treated Johannes. He then ran away from home, seeking refuge in a Buddhist temple nearby, even though he was a Roman Catholic. It was in the serene and tranquil setting of the temple that he mastered Sinhala under the tutelage of the monks.

Much later, he had made a name for himself and a niche in the hearts of the Sinhala teachers. However, as suspected pleurisy wracked his body, the authorities sent him to Jaffna, from where he would never return to his beloved walauwwa. He died at 58.

With no facilities to bring his body back home, wife Elizabeth and eldest son, Cyril, journeyed to the north to bid a permanent adieu to Johannes.

He would not be able to see his youngest son Oswald who was born in 1911 after he left for Jaffna, says Priyadarshini, recalling how her father would reminisce how he came upon the princely sum of two thousand rupees left amidst the leaves of a book by Johannes.

“When my late father saw my grandfather’s grave in Jaffna on a visit there, he was visibly upset,” she says, adding that she believes that her father had taken to medicine and was heavily involved in the treatment of tuberculosis because of his own father’s demise due to such an illness.

And so, as Priyadarshini who has returned to Sri Lanka after a long and successful career as an award-winning Research Scientist in America, dips into the past, there is only one fervent wish – to restore for posterity, the glory of ‘Senanayake Walauwwa’, the home of an eminent Sinhala scholar of yore.