That’s poetry to me

View(s):‘Talking within myself to myself and other

Selves I encounter along the way,

That’s poetry to me’

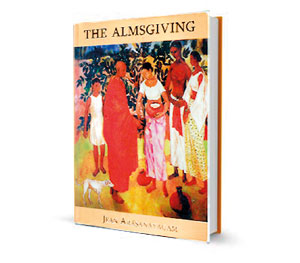

The Almsgiving by Jean Arasanayagam (2014) is a contemporary collection of poetry with great relevance to the post conflict but still harsh era in which we live.There are poignant cameos of real events and people and it is testimony to the humanity of Jean Arasanayagam that several tributes deal with injustice, and applaud the ‘dissidents’ of this world. She talks urgently of the death of Zo Claudio, the Brazilian conservationist, anti-logger and protector of the rain forest who was ambushed with his wife and killed.

The Almsgiving by Jean Arasanayagam (2014) is a contemporary collection of poetry with great relevance to the post conflict but still harsh era in which we live.There are poignant cameos of real events and people and it is testimony to the humanity of Jean Arasanayagam that several tributes deal with injustice, and applaud the ‘dissidents’ of this world. She talks urgently of the death of Zo Claudio, the Brazilian conservationist, anti-logger and protector of the rain forest who was ambushed with his wife and killed.

ZoClaudio, Shot and Killed is almost a list, void of breaks,an outpouring of outrage as the poet takes up the mantle, protesting apocalyptically against the looting of the earth ‘existentialist landscape that spells the doom of a rain forest covered with bleached strands of grass …earth ….left to harden into dwarfed monoliths.’And about the death of its protector ‘You, Zo Claudio the guardian of a universe that will soon be vanished and extinct.’

Another of these tributes is for Ngnuyen Chi Thien, who the poet has never met but calls ‘fellow poet, fellow friend’.‘This Vietnamese dissident was imprisoned and in labour camps for 30 years where he continued to write poetry and this ‘freedom’poet’s ‘thousands of lines kept him still alive in our hearts and in our minds.’ Jean Arasanayagam emphasises the word Dissident,writing it several times and defining it as one ‘who chooses to step out of the regimented ranks – branded with the mark of Cain….’

These are strong courageous acknowledgments to lesser known heroes. Brought forcefullyinto our line of vision, we are forced to look, to see further afield, towards these ‘dissidents’, these ‘refusers’ from far flung counties who live their life in fear of imprisonment or death but still are able to reign ‘suzerain over the down trodden masses’

Ngnuyen Chi Thien himself says in Verses (1969)

My verses are in fact no verses

They are simply life’s sobbings

There is something of these ‘sobbings’, this suffering that suffuses Jean Arasanayagam’s work and is present in a number of dedicated poems and cameos in this well-travelled patchwork of poetry.

The poem for Nirbhaya, India’s Daughter-Braveheart is not a tribute but a vital testimony of these barbaric times; horribly symbolic, it represents a pinnacle of violation. In the poem, the victim whispers ‘save me save me I want to live’and the poet tries to offer comfort, to remove her to another better place, a mystical place, another world. ‘You are far beyond human mortality’.Arasanayagam shows paradoxical gentleness as she details the horrors ‘The world’s daughter caught up in the rape of civilisation’ ….’We light candles to you Braveheart, you become the vestal virgin in this hideous world the horror filled darkness of evil’.

The dichotomy between powerful and vulnerable appears in a number of poems including Boxing Day Hunt, Tally Ho!A certain conventional brutality is shown ironically through the atmospheric Constablesque images of the English countryside. But we see the chasm between rich and poor, animal and human, hunter and hunted,‘That powerful urge to give vent to that pulsating desire to pursue hunt chase kill a victim vulnerable and less powerful than brutal man…’.

Still there is hope, perhaps the fox will get away and the poem ends taking note perhaps with a hint to Karma, of the fragile balance of ‘hunter hunted’ ‘human prey hunted down by packs of foxes…..what it is to be a vulnerable victim’.

There are also stark contrasts between rich and poor in Aerial View where the poet saunters through the vast pleasure gardens of extreme opulence of the Middle East, then takes a glimpse behind the scenes to images of ‘migrant workers feet wrapped in strips of gunny sack’. In an almost impossible repetition of horror it ends, ‘beaten up, tortured, starved executed, lashed or stoned to death.’We are overwhelmed by cruelty and barbarism, but as always with Jean Arasanayagam, it is the unexaggerated truth.

The poet is able to use her infinite empathy most touchingly to express the lives of the poor in Damini. The child’s father holding his weak daughter against his body offers an ordinary, yet extraordinary glimpse of humanity and optimism. ‘Baby Jadav’s daughter peddling through the streets of Bharat put Damini, his life’s breath feeling the warmth and strength of her father’s body in a homemade papoose.’…..‘Her karma has been good she will stay alive, tended nourished’;there is no belittling, no pity for the poor, more a sense of admiration.

The issue of identity which pervades all Jean Arasanayagam’s work is also present here.In an interview which serves as a foreword to the book(from June 2012), Katerina M. Powell asks

KP: ‘ ..In some of your work you go back to your family’s history and you grapple with the tension of having the colonizers….’

JA: ‘Yes …as my ancestors, history sometimes becomes a masquerade to me’

KP: ‘the coloniser’s blood may be mixed with…’

JA: ‘…Yes, mixed with indigenous blood’

In her earlier book Reddened Water Runs Clear (1991) she wrote,‘It is so easy to say that one’s ancestors were degenerate or exploiters or that they were the lazy hoboes of the seaboard’.

In the Almsgiving, Renaissance Woman begins with a tirade of horrors perpetrated by the colonisers:‘Unleashing their way of life on those who could not resist …the rabble marauders dealing with the battered flesh of slaves.’ But ends with the poet’s own conception, ‘So if I begin here….waiting to enter the dream womb of the future….what nation do I begin to invent or strip of exoticism, my existence?’

In Image of Otherness (….) Dr Gerard Robuchon elaborates further and believes that Arasanayagam’s writing ‘is an attempt to overcome a colonial ancestry she did not choose. Indeed it questions the official ‘identity marking’ to claim the writer’s right to a multifaceted Sri Lankanness, miscegenation of all cultural backgrounds’.

She may have no ethnic group or many but it is clear that her inheritance does not limit her compassion.

In the poem, Almsgiving, Part 1 the theme of dana which poeticises the cover painting by Neville Weeraratne is explored. The depiction of simple rice is so deliciously described and hunger, mentioned both ‘’physically’ as poverty, drought, failed harvests and spiritually ‘the selfish hunger of our emotions searching for ecstasy to fill our empty hearts, our starving lonely lives’.The fundamental notion of giving is examined in depth. In Part 2 of the same poem, we see that it is not only Buddhists who engage in dana but at Ramazan ‘’jugs of canjee steaming hot are sent by neighbours’.

The sublime language of the poems is enthralling. At times it is stream of consciousness; the writer herself says that words flow like rivers, ‘inspired stanzas to the rhythm of its flow’. They flow epically, spilling over in a pattern of constant enjambment; the poet’s loquaciousness and inner talking take precedence over form. The uneven chunks of poems are not even limited by our need for breath;they are urgent words that cannot be stopped; a luscious overgrown garden the poet does not want to curb; an organic structure,which tellingly has noboundaries Words have the upper hand and de-emphasise form, creating their own metaphorical rhythm; however mindfulness keeps this outpouring in check. The poems are written in strikingly beautiful English and the poet ekes out complex language sometimes transforming it creating words like left behinder and stanziac.

She appears regularly in Meta-text talking of herself and her poetry and poetry in general. . ‘inside a cell of her own making’‘her body a poem’‘myself spilling out on the page before me powerful storms of words’‘The poet must wear uniform lose his identity in a cause….’

The world of today is a brutal one with bomb blasts and horrific rapes as if evil, not as clearly identifiable as before has taken over. It is a world that has forgotten and where there is no ‘remembrance of the rituals’. Jean Arasanayagam portrays this world and much more and does so courageously, with outrage and compassion, empathy and urgency and as always there is no ‘glossary’, no ‘paraphrasing’ for the reader who must partake of her overwhelming bravery and that of her protagonists. Her work drives us to the core of our own humanity as we are trusted to find our own way through the packed pages of nearly 50 poems of which I have merely skimmed the surface.

- Reviewed by Patricia Melander