This PET is a grave need

Subodha and Sasen. Pix by Indika Handuwala and Anuradha Bandara

A mother and her little son are gently moving back and forth on a brightly-coloured outdoor-swing.

They are not in a playground for the afternoon, when we meet them on Monday, but just outside Ward 16, the Paediatric Ward of the National Cancer Institute at Maharagama.

Heart-rending are the scenes that pass before our eyes, as we talk to Subodha Suranji, a teacher from the south.

All children here, both girls and boys – some very tiny, others not so tiny – are walking about shaven-headed or wearing face-masks.

Like the parents here, Subodha is in the vice-like grip of worry and anxiety. Since 1½-year-old Sasen Sandinu was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma (a common, highly malignant primary bone tumour of childhood) it is double jeopardy for Subodha and her family. Days and nights of worry over Sasen’s illness are exacerbated by money issues, for an essential series of tests, not only for accurate diagnosis but also to check for the spread of the cancer and whether the treatment is working or not, will cost an exorbitant Rs. 155,000 each time.

These are the PET (positron emission tomography) scans essential and considered the ‘gold standard’ in the diagnosis and treatment of certain cancers such as lymphomas and malignant growths.

No government hospital including the National Cancer Institute in Sri Lanka has the PET scan machine. It is only available at a private hospital in Colombo and that too at a dear cost.

While Sasen takes tiny bites off a cream cracker, with his mouth marked by biscuit crumbs, Subodha says that they could ill-afford the Rs. 155,000 which they paid up on April 23 for the first PET scan.

“Our friends got-together and collected some money, relatives lent a helping hand and my mother-in-law also gave a contribution,” sighs Subodha, adding that although initially they were told that the PET scan would cost Rs. 155,000, there were other “unseen” costs and ultimately they paid up Rs.158,000.

This is the plight of numerous children and their families who are faced with a mountain of extra bills which would include transport and food costs along with the massive PET scan costs. Many of these children’s parents may not be earning this princely sum even after a year’s toil and work.

Another factor in the equation would be that the whole family’s usual routines including the livelihood and employment of the parents may be at a standstill, as they deal with cancer and the long stays at the National Cancer Institute.

For Subodha’s middle-class family, with another five-year-old son back at home, every rupee is precious. They were managing on their income until a lump near Sasen’s right ear was removed at the Karapitiya Teaching Hospital and a biopsy threw forth a red signal which indicated malignant cells.

Not only seeing but also experiencing what these parents are undergoing, one among them is now on a quest to help the National Cancer Institute purchase its very own PET scan machine. Businessman and Founder President of the Kadijah Foundation, M.S.H. Mohamed is also grappling with the tangible sorrow of his one and only son, 17-year-old Mohamed Humaid, battling an osteosarcoma (a cancer that starts in the bones) in his shoulder.

When his son was diagnosed with the osteosarcoma, Mr. Mohamed took him to a private hospital in Chennai, India, for treatment. During the whole of 2014, they were at this high-tech state-of-the-art hospital and Mr. Mohamed dug deep into his pockets.

“I sold three valuable properties,” says Mr. Mohamed, explaining that when the money was running out he was forced to seek treatment for his son back in Sri Lanka. Then too they were at a private hospital here for six months, with his teenage son undergoing two surgeries in both his lungs. As the bills and the cost of medications kept rising, the family was compelled to seek treatment at the National Cancer Institute.

It opened their eyes to reality – the treatment was equally good at this state institution and the medications cost much less, he says.

His son was in Ward 16 and the family was taken by surprise. The misconceptions about government hospitals were instantly dispelled. “The staff is excellent and for the first time since we came face-to-face with cancer we were offered counselling,” says Mr. Mohamed, adding that they had very experienced doctors who were also very kind. The service rendered by the staff at the National Cancer Institute was commendable.

Having made good in life, after arriving in Colombo from Kalutara his home town, with just 100-rupees in his pocket and then setting up Kadijah Foundation to help all children, be it Sinhala, Tamil or Muslim, across Sri Lanka, Mr. Mohamed on seeing the dedication of the National Cancer Institute staff was driven by a different quest.

For all the good work that they were doing, he wanted to give something in return. When he asked them what the urgent requirements were they revealed that there was a dire need for a PET scan machine as well as a genetic laboratory.

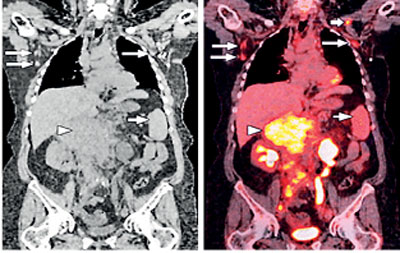

A CT scan and on the right the PET scan clearly lighting up the cancerous areas

He too had felt the need of the PET scan machine for his son has already had around 10 PET scans, costing more than a million rupees.

Using his business acumen, he has now set in motion a plan to raise the Rs. 200 million required to purchase a PET scan machine for the National Cancer Institute.

The money is trickling in, with contributions ranging from Rs. 50 to a million rupees being credited towards this worthy cause every minute.

Rupee by rupee, Mr. Mohamed is sure that his dream of getting the PET scan machine for Maharagama will see the light of day, helping hundreds of men, women and children who cannot afford to get these scans in the private sector and face death, in vain, for lack of money.

| Every little bit counts Appealing to each and every Sri Lankan to give of their mite, Kadijah Foundation President M.S.H. Mohamed has initiated a drive to collect the Rs. 200 million to purchase the essential PET scan machine for the National Cancer Institute at Maharagama. Contributions may be sent to: Bank Account: 0071275069 at the Bank of Ceylon, Maharagama, Sri Lanka, with the Account Name: National Cancer Institute, Maharagama. The Swift Code is: BCEYLKLX, Branch Code is: 055 and the Bank Code is: 7010. For more information, please contact Phone: 0094-11-2897377/78; E-mail: info@fightcancer.lk or check out the website: www.fightcancer.lk Mr. Mohamed has also set up a small army of 70 ‘Fight Cancer Soldiers’ to continue to support the National Cancer Institute, while there is an active ‘Fight Cancer Team’ WhatsApp Group. |

| Why the PET scan matters It is Consultant Paediatric Oncologist Dr. Mahendra Somathilaka attached to the National Cancer Institute who dwells on the importance of the PET scan machine in treating certain cancers. Before explaining the need for PET scans, he stresses that cancer is not equal to a death sentence. “Cancer is a curable disease. It is a myth that cancer is equivalent to a death sentence. Eighty percent of those who are afflicted by leukaemia and haematological malignancies can be cured.” Focusing on malignancies, he says that whenever someone has a lump or growth, a biopsy is carried out to confirm whether it is a cancer. Once that is confirmed, there is a need to determine whether it has spread to other sites of the body. This ‘staging’ is done through clinical examination along with radiological imaging. Radiological imaging plays a main role as it provides solid evidence of what the situation is within/inside the body. “Presently, we make a clinical diagnosis depending on the symptoms and then get either a Computed Tomography (CT) scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). However, CTs and MRIs are a little less sensitive, as in some patients differentiation between normal tissue and cancerous tissue is difficult. This is because cancer tissues can mimic a normal structure,” says Dr. Somathilaka, pointing out that this is why for staging the more sensitive PET scan is needed. CTs and MRIs may sometimes lead doctors astray that the cancer is localised (in the place where detected), even though there are other metastatic areas. This would result in under-treatment of the cancer. However, the PET scan will clearly light up the cancerous tissue. This Cancer Specialist who treats children and adolescents cites the example of a tumour such as Ewing’s sarcoma where without a PET scan, surgery is done under the assumption that it is localised. However, a PET scan may catch other metastatic areas such as a small lump in the lung. Then there will be no under-treatment. “A different scenario could arise when we feel the lymph nodes and think the cancer has spread and thus over-treat the malignancy. The PET scan is a standard test in the case of lymphomas,” he says, pointing out that a CT scan may, meanwhile, show a small lesion, which the doctors would treat with high doses of chemotherapy. But it could be some normal tissue and the over-treatment could kill the patient as the side-effects of the chemotherapy are very toxic. PET scans, however, would indicate both the primaries and the other metastatic areas, it is learnt. After initial treatment too, a second PET scan would help assess the effectiveness of the treatment and the response of the cancer and depending on the findings – whether there has been a retardation or not – medications can be changed or therapy switched to suit the patient. “In 70-80% of those having solid tumours, especially sarcomas and some cancers, PET scans are essential,” says Dr. Somathilaka. Showcasing Sri Lanka’s achievements, he says that in the treatment of leukaemia (blood cancer), the country is only slightly below western standards but in the treatment of solid tumours “we are quite substandard”. Referring to how PET scans work, he explains that cancer cells are highly active metabolically and need more energy than normal cells. They take up the energy from glucose. When taking a PET scan, a radioactive dye attached to synthetic glucose molecules is injected into the patient. When the cancer cells take the synthetic glucose, the radiological substance lights up, clearly showing active and non-active areas.

|