Tagore: A man of many roles and master of all

This weekend marks the 156th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore (1861- 1941), the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, and no stranger to Sri Lanka and “identified as a man whose spiritual personality and unremitting efforts in the arena of international understanding inspired the entire world”.

This weekend marks the 156th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore (1861- 1941), the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, and no stranger to Sri Lanka and “identified as a man whose spiritual personality and unremitting efforts in the arena of international understanding inspired the entire world”.

To refresh my memory about the most famous Indian of modern times, with the exception perhaps of Mahatma Gandhi, I referred to ‘Great Men of India’, one in a series of the Home Library Club publications (late 1930s), I had acquired from my father’s collection. I was fascinated by the life sketch written by Dr. K. S. Shelvankar, journalist turned diplomat, who introduces Tagore as being known from Japan to Scandinavia and from Moscow to Buenos Aires, and venerated in his own country as a poet and philosopher in the tradition of the ancient rishis. He quotes German philosopher Hermann Keyserling, who said Tagore is “the most universal, the most encompassing, the most complete human being I have known.”

Calling the Tagores one of the first families of Bengal, Dr. Selvankar traces Tagore’s ancestry. They were not only great hereditary landowners (zamindars) but were noted for their munificent patronage of art and literature. Originally Banerjis, they were believed to have settled in West Bengal in about the 8th century CE. In the 17th century they received the appellation of ‘Thakur’, which means “respected Lord” or seigneur.

“Defiance of orthodoxy appears indeed to be one of the characteristics of the Tagore family,” says Dr. Selvankar. “They are supposed to have broken caste rules by eating with Moslems. This offence cost them their place in the Brahman community; and notwithstanding their great wealth they were looked down upon with contempt as ‘pirilis’. No strictly orthodox Brahman would either eat of intermarry with them.”

Young Tagore did not much care to go to school. He was allowed to follow private lessons. He did not much like that idea too. “His mind was at once too eager and too dreamy, too independent and too sensitive to fall readily into the conventional ruts,” says Dr. Selvankar. The father being a regular traveller, he took the boy on his wanderings which the young one liked very much.

He had begun to write verse almost as he could walk; his work appeared in print when he was fifteen. Before he was 18 he had published nearly 7,000 lines of verse and a great quantity of prose.At 16 he went to England where after being at Brighton school for a while, he joined University College, London.He returned after about a year.

In his early twenties, he went through a moment of mystical illumination – the first of many such experiences – which he said left a deep impression on him. He describes the first experience in his ‘Reminiscences’ thus: “One morning I happened to be standing on the verandah. The sun was just rising through the leafy tops of those trees. As I continue to gaze, all of a sudden a covering seems to fall away from my eyes, and I found the world bathed in a wonderful radiance, with waves of beauty welling on every side. The radiance pierced in a moment through the folds of sadness and despondency which had accumulated over my heart, and flooded it with this universal light.”

The model school

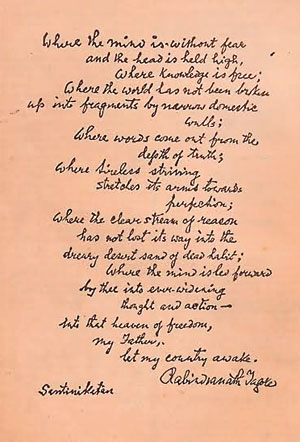

Tagore is synonymous with Santhiniketan, the world famous school in performing arts which he established in 1901. In Dr. Selvankar’s words, here he hoped to recapture the meditative calm of ancient India and provide an environment where the mind of the young “might expand into love of Beauty and of God”, as Tagore put it. The school was described in the 1930s as a model institution where the study and revival of Indian culture in all forms go hand on hand with Westernised and most modern methods of education.

He faced a series of tragedies starting with the death of his wife in late 1902 and successive years saw the deaths of his daughter (1904), his father (1905) and son (1907). Meanwhile, he continued to write verse, short stories, novels and plays which were being widely accepted. Among them was the novel ‘Gora’ described as “a long story with the fullness of detail of the Russian novel,” and ‘Gitanjali’ , a book of religious poetry hailed as the authentic voice of one who, through much suffering, had attained joyous serenity.

Tagore met Gandhi and his disciples when they came to Santhiniketan and spent a few days after their return from South Africa in 1915. “Much as the poet admired the politician-saint, there were deep differences between them –differences which rose to the surface when Gandhi launched the non-cooperation movement. Rabindranath was profoundly opposed to it. He condemned its narrowness of spirit; he feared its further consequences; he deplored the effect it was having on the lives of the young; and he derided the glorification of the ‘charkha’,” writes Dr. Selvankar. Tagore was freely attacked for this attitude but he stood his ground. Quietly he pursued what he held to be the true ideal of nationalism and internationalism by founding the Culture – ‘Viswa-bharati’, and by starting a Department of Rural Reconstruction- ‘Sriniketan’to develop village welfare work that he had begun in 1914.

Meanwhile his popularity abroad was increasing. A cult of his work sprang up. Between 1920 and 1930 he undertook no less than seven lecture tours in the West, in Europe and in America. In 1930 he visited the Soviet Union.

“Rabindranath’s literary achievement is prodigious; it overshadows everything else,” says Dr. Selvankar. He adds: “It should be recorded, however, that he was not only a poet, playwright and novelist, but a musician, actor, painter, composer, philosopher, journalists, teacher, orator, and a host of other things – and distinguished himself in each of these very different roles. There is no more versatile, prolific and gifted genius in history.”

Tagore went on foreign tours where he made a name for himself. After a visit to America he returned in the latter part of 1913 universally recognised as one of the foremost poets of the age. Within a few weeks he was conferred the Nobel Prize for Literature and Calcutta University crowned him with academic laurels soon after. In 1914 he was knighted.