Exploratory expedition into uncharted territory in Sri Lanka

View(s):

At the launch: (L-R) Dr. Mario Gomez, Jayantha Jayasuriya, Attorney General, Justice Priyasath Dep, Supreme Court Judge, Dr. Avanti Perera, Narendra Kumar, Chairman, Har-Anand Publications and Prof. Colvin Goonaratna

My first meeting with the author, Dr. Avanti Perera, D.Phil (Oxon); LLM (Cantab); BA (English) (Colombo), a Senior State Counsel, was when she came to my cluttered office in the Faculty of Medicine in Kynsey Road several years ago, by prior appointment, to have a chat with me on my views about clinical negligence. The principal reason for her visit was obviously because I had written a book on the now famous Professor Priyani Soysa versus Rienzie Arsecularatne case, where I had been studiedly critical of the judgments of the District Court and the Court of Appeal. If my memory serves me rightly, we discussed very briefly at that meeting about the D. Phil from the University of Oxford Avanti was aiming for, and I believe that I was able to warmly encourage her. I had the privilege of reading her D. Phil thesis in its entirety at leisure, after her return to Sri Lanka a few years later.

I want to start the review proper, if I may, with a quotation from The Economist, widely acknowledged as the best periodical journal in the world for its news, views, immaculate style and the impressive accuracy of content. The issue of this journal I’m quoting from is dated December 31, 1999 – the dawn of the new millennium, you remember? This particular edition was called the Millennium Special Edition, and had the arresting by-line “Reporting on a Thousand years”, from January 1 year 1000 to December 31 year 1999. It carried some dazzling essays on the world’s wealth, health, population, work and employment, rights, democracy, and the right to law. The quotation I am giving you now, is the last paragraph of the essay titled, Right to Law.

“The institutions of law exist almost everywhere. Yet much of the globe remains literally lawless. Property rights and civil rights are the preserve of a small elite, or even pure fiction. At best, civil law is often what a corrupt judge says it is, and crime is often what such judges say poor men have done but rich ones not. And the biggest threat to life and liberty is often the very government that poses as the guardian of both.”

Not a very flattering summary of the institutions of law in the last millennium! Probably not applicable to the land celebrated in a couple of very popular Sinhala songs as the “noblest country in the world”. By appropriately changing a few words, the quotation I have given may be used also to describe healthcare institutions in the planet earth in the past millennium, perchance even in the last five decades. Perhaps I digress. I must come to Avanti’s book, which deals with matters germane to healthcare and clinical negligence claims.

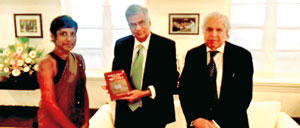

Presentation of the book to Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. Justice Priyasath Dep is also present

Avanti’s book has nine chapters including an Introduction (Chapter I) and Conclusions (Chapter IX). I mention here the titles of the other seven, just to indicate their extensive reach in regard to medical negligence claims in Sri Lanka. They are in order of presentation, Identity of Parties and Emergence of Grievances, Substance of Grievances, Dispute Conditions and Grievance Management, Goals Pursued by Claimants, Claims Forums and Capacity to Claim, Claims Processing and Outcomes via Legal Forums, and Claims Processing and Outcomes via Non-Legal Forums. No stone has been left unturned. And so, all nine Chapters when taken together provide a virtual cornucopia of Sri Lankan research findings, with incisive interpretations of the author, and where relevant, reference to similar facets from foreign negligence claims and anglophone jurisdictions.

Doctors are exhorted from their medical student days, to consider patients) “as human beings in trouble,” which says it all. But all too often we doctors tend to forget this, and refer to our patients thoughtlessly as “cases”. Overall, patients, their guardians, and heirs who seek redress for perceived negligence of doctors, nurses and other health service providers, from the few sources available to them, are seen by such providers as pesky moaners or worse. These comments are of course generalisations, and I admit that there are shining exceptions among doctors and nurses, but they are I believe to be a small minority.

Against this background, Avanti has undertaken, most successfully, an exploratory expedition – at least as far as Sri Lanka is concerned – into uncharted territory. The book I am discussing is the outcome of that expedition. Her approach to medical negligence is refreshingly new. It is a socio-cultural study of claimants and clinical (medical) negligence claims in Sri Lanka, skilfully intertwined with the more familiar context of their medical and legal bearings.

The principal evaluative instrument in her investigation is the direct face-to-face, open-ended, unstructured but imperceptibly guided interviews and discussions with claimants in 40 clinical negligence claims. Such interviews are, of necessity, retrospective, subjective and qualitative. However, this particular evaluative instrument is comprehensively dispute-centred and based on the well-recognised case approach, which seems both appropriate and sufficient.

| Book facts Medical Negligence Claims in Sri Lanka, by Avanti Perera. Har-Anand Publications, New Delhi -110020; 2016. Pages 317. Reviewed by Professor Colvin Goonaratna Available at M.D. Gunasena (Hulftsdorp, Bambalapitiya & Kandy) and BASL Bookshop, Hulftsdorp |

Avanti has also unearthed a wealth of valuable information on patients’ knowledge on levels of healthcare, access to information on adverse events, trust in healthcare providers, consumer consciousness, and so on, from a cohort of 64 patients drawn from four major public sector hospitals, three major private sector hospitals, and one semi-government teaching hospital. The revelations of this part of her investigation may come as a surprise to those who have had no previous access to such information or to the first-hand experiences that the more perceptive and humane doctors and nurses have encountered during their daily working lives. Her investigative and analytical methodology is, in my view ideally fit-for-purpose, and a well recognised one in dispute studies.

Medical doctors and statisticians immersed deeply in the relatively new and worthy concepts of “evidenced-based medicine” and so-called “levels of evidence” based on this concept, may find it hard to reconcile their ideas with the investigative methodology employed by Avanti. Without entering into the apparently never-ending controversy about the nature of evidence in respect of the inductive and deductive approaches to scientific knowledge, I confine myself to quoting from the prestigious Harveian Oration of the Royal College of Physicians, delivered in the year 2008, in London. The orator was Professor Sir Michael Rawlins, Chairman of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (a.k.a. NICE), and the title of his oration was “De Testimonio”. It is all about the nature of evidence.

“The notion that evidence can be reliably placed in hierarchies is illusory. Hierarchies place randomized control trials (RCTs) on an undeserved pedestal for, as I discuss later, although the technique has advantages it also has significant disadvantages. Observational studies too have defects but they also have merit. Decision makers need to assess and appraise all the available evidence irrespective as to whether it has been derived from RCTs or observational studies, and the strengths and weaknesses of each need to be understood if reasonable and reliable conclusions are to be drawn.”

I believe that this quotation would suffice, for the time being, to allay the concerns some readers of her book may have about the reliability of the author’s investigati Thus far I have briefly discussed only the process of investigation, and analysis of the outcomes derived from that exercise. I must address myself now to another question. In what ways has the reading of Avanti’s book, and the PhD thesis on which the book is based, changed my views regarding clinical negligence claims in Sri Lanka? The short answer to that question is, in a multitude of ways. It has certainly sharpened and circumferentially extended several untested ideas I had formed during the writing of my book on the famous Priyani Soysa case. Perhaps more importantly, Avanti’s book has opened my mind to issues that impress upon the entirety of clinical negligence claims and claimants, as never before.

For example, well over one half of patients’ claims recorded by Avanti appeared to have “non-clinical” grievances such as ‘dismissive attitudes of doctors and nurses’, ‘arrogance’ and ‘their lack of communication.’ ‘What I am angry about is that the doctor did not tell me something had gone wrong and went on treating me………’ ‘When I complained that the patient was in pain, the house officer responded “What do you know, you are not a doctor”…… I felt like killing him’ are just two comments taken from the many narratives of patients quoted verbatim by Avanti. In microcosm they are illustrative of patients’ and their relatives’ cries of despair and helplessness when in serious trouble, not gratuitous or groundless criticisms of doctors’ and nurses’ actions, as often supposed. They also give some idea of how infuriating the dismissive and arrogant responses of healthcare providers can be to helpless people in trouble, for one respondent has exclaimed ‘I felt like killing him (the rude doctor).’ Avanti mentions, without in any way justifying or condoning it, the most tragic case of a soldier father who shot dead a doctor, allegedly because of the callous way that she spoke to him for the second time in one day, when he went with his ailing son to see her.

The most overwhelmingly striking observation I gathered from Avanti’s narratives, is that clinical negligence claimants in Sri Lanka are all but denied access to justice; the indigent and helpless vastly more than the rich and influential. You will here recall the perspicacious quotation from The Economist. The Ministry of Health is full to overflowing with medical doctors, all or most of whom are members of a trade union whose boast of being somewhat powerful depends entirely on most cruelly holding innocent and helpless patients to ransom by frequent unethical strikes or threats to strike. The Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC), also entirely constituted by medical doctors, many of whom are active members of the same trade union, is a law unto itself. To appeal to it requires an affidavit – hardly the mark of a people-friendly institution. Both the Ministry of Health and the SLMC are inappropriate and inadequate institutions I believe for ensuring justice to claimants in cases of alleged negligence, in view of their composition, their collegiate nature, and scant knowledge of the law.

Consequently institutes of law remain the only avenue for clinical negligence claimants in Sri Lanka seeking reparation that are free from glaringly obvious collegiate conflicts of interest and with (presumably) sufficient knowledge of the relevant law. But the institutes of law are generally accessible only for the rich and the influential. And I have stated in no uncertain terms in my book on the Priyani Soysa case, my view of the judgments handed down in the District Court and Court of Appeal. So I do not speak about that aspect here. I would venture to say only that judges who preside over clinical negligence cases ought to be those who have undergone dedicated training in essential aspects of adjudicating in such cases, with a good knowledge of the increasing complexity internationally of medical technology and interventions such as major organ transplantation, in vitro fertilization, artificial insemination, surrogate pregnancy, brain death, and so on, and their legal implications. The Woolf Report (Lord Justice Woolf, 1996, Access to Justice; HMSO, UK) is a fine example of the sort of amendations required in the dispute and grievance resolution mechanisms and legal processes, to facilitate delivery of justice to claimants and defendants alike in Sri Lanka too, within a civilised time-frame.

The term ‘medical error’ ought to include errors of commission and omission of all categories of healthcare workers such as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory technologists, physiotherapists and so on, and also by composite healthcare teams such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation teams. Defined so, medical errors, whether negligent or non-negligent, are extremely common. Many are trivial, harmless and go unnoticed. Some are detected early and corrected before they cause any harm. The remainder will cause minor or major harm, with some errors in the latter category causing the harmed patient’s death.

A recent Commission of Inquiry in the USA reported that among patients dying after admission to hospitals in that country during one year, the cause of death was avoidable medical error in over 95,000 cases. Many others had been more or less harmed by avoidable medical error. The true extent of the avoidable harm inflicted on hospitalised patients in our state and private sector hospitals can be measured only by such independent, confidential, comprehensive, and regular inquiry. The quality of care patients receive in health care institutions in Sri Lanka has never been carefully examined in that way, save for one or two sporadic, once-in-a-lifetime limited studies.

In a pioneering and historic article authored by Professor Carlo Fonseka, published in the internationally prestigious British Medical Journal on December 21 1996, he has described in detail what in his judgment were five fatal medical errors he made during a lifetime of 36 years. I can give a recent reference to this article to anyone who requests it. He summarises his article with five “Key Messages.” I want to end my review by reproducing them here, in bullet form.

All doctors are fallible.

The natural reaction of all doctors is to hide them or rationalise them away.

It is unscientific and unethical to refuse to face our errors.

There is no cathartic ritual in our profession to expiate the sense of guilt generated by our errors.

Since knowledge grows mainly by error recognition, facing our errors squarely is the path to medical wisdom.

To make these key messages more meaningful and inclusive, Carlo please forgive me if I add the words ‘and nurses’ after the word ‘doctors’.

I congratulate Dr. Avanti Perera for her original research into Medical Negligence Claims in Sri Lanka, and for publishing her findings comprehensively in the form of a book, in stylish diction. Reading it is strongly recommended for all doctors, lawyers, sociologists, health planners and all others who have patients’ welfare in their hearts.

( The reviewer is Chancellor, Open University of Sri Lanka)