News

Rape of wetland leads to floody hell

The residents of Joy Lanka Watta, a housing scheme in Kohilawatta on the outskirts of Colombo, still remember the lake. It had stretched out for as far as the eye could see. In the early mornings, the air echoed with birdsong. People had fished there, or waded into its still waters to pick red lotuses to offer at the temple.

The residents of Joy Lanka Watta, a housing scheme in Kohilawatta on the outskirts of Colombo, still remember the lake. It had stretched out for as far as the eye could see. In the early mornings, the air echoed with birdsong. People had fished there, or waded into its still waters to pick red lotuses to offer at the temple.

Several years ago, trucks had started trundling up with garbage, rocks and soil. The contents were tipped into the water. Residents say it was done at the behest of a sawmill owner who they identified as Ajith. He had staked claim to the land bordering the lake. Refuse piled up, attracting rodents and crows.

Unable to bear the stench, the people protested. Some of them signed a petition, drawing threats from cohorts of a notorious mobster from Grandpass. The Special Forces once towed the trucks away. But Ajith was well connected and received patronage from politicians. The trucks returned — and kept coming, till all but a small corner of the lake was topped.

Houses on the bank of Kelani River that were flooded out. Pix by Indika Handuwala

“Everything happened recently, during the tenure of the last Government,” said a local government official who requested anonymity out of fear. “We complained to the police but they did nothing. That’s all I can tell you.”

What occurred here is typical of the manner in which many marshlands in the Colombo metropolitan region have been reclaimed. The perpetrators, usually well-connected, are accountable to none. The police know better than to intervene. The filling is done against the law. And it continues.

Even today, there is a pile of rocks and soil at the edge of Ajith’s reclaimed plot. It is clear that he intends to choke the rest of the lake. His property is now higher than adjoining areas. Last month, Joy Lanka Watta was severely flooded when the Kelani River burst its banks. Runoff from Ajith’s reclaimed plot made matters worse. And without the lake to retain excess water, many other houses also went under.

R. A Sriyani, a cleaner who lives at the edge of Kelani River

Eighteen percent of the Colombo metropolitan region was made up of wetlands in the 1980s. The number is now down to just 10 percent. This means a massive 40 percent of wetlands have been lost to planned or unplanned development. Studies show them continuing to diminish at the rate of 1.2 percent per year. This will make flood mitigation even more difficult in future.

There are multiple other impediments to flood management in Colombo and its suburbs. In recent decades, flood plains all along the serpentine Kelani River have become heavily built up. Kolonnawa, for instance, is constructed almost entirely on low-lying ground adjacent to the river. It is packed solid with homes and businesses. They were among the worst hit.

Even the bund of the Kelani River has been compromised by unauthorised dwellers. So crowded is the Colombo metropolitan area now that finding other lands for them to live on is proving a serious challenge. A sense of urgency prevails.

At the picturesque Ganewatte Purana Maha Viharaya in Bomiriya, a mass of people gathered anxiously around Kaduwela Divisional Secretary W.M. Dayawathi. They had lived atop the Pahala Bomiriya bund of the Kelani River but their homes were destroyed in the flood. The Irrigation Department has warned them to vacate the embankment. But they had nowhere to go and the Divisional Secretary had nowhere to put them.

“There are no State lands in the Kaduwela division to shift you to,” Ms. Dayawathi explained to them, staring worriedly at the sky. “We will find a solution for you but we need time. We cannot do this at once. So stay where you are for the moment and give us time.” It was decided that the settlers would pitch their donated tents on a property adjoining the bund till a more suitable option presented itself.

Settlers on the Pahala Bomiriya bund

A few yards away, B.B. Anuruddhika’s phone rang ceaselessly. She was the Pahala Bomiriya Grama Niladhari, a tireless woman that residents had high praise for. “I have been on my feet for more than 15 days,” she said, eyes brimming with tears. Her husband, a postal worker, was paralysed in a stroke nine months ago and could not understand why she kept returning home past midnight. She was also juggling three children, the youngest of whom was just nine.

In some parts, people have built homes between the bund and the Kelani River. Not only is this dangerous, it impedes the smooth flow of water and prevents the authorities from reinforcing or heightening the banks. Any flood management plan, experts warn, must take into account these obstructions.

R. A. Sriyani, a 43-year-old cleaner, lives in a hovel in Kelanimulla with two children. It is made of wooden planks with tin sheets for a roof. There is a long row of such dwellings, all perched at the edge of the Kelani River. To access them, one must climb over the bund and down roughly-hewn steps. Full-sized families are crowded inside with several offspring.

Sriyani says she would leave in a jiffy if the Government gave her land. Her toilet (a squatting pan in the corner, separated by a partition) was washed away in the recent flood and her house is leaning precariously towards the water below. “If someone gives us a plot,” she enthused, “we will worship that person instead of the gods. We don’t want a house or anything else. We will put something up to live in.”

What used to be a lake near Joy Lanka Watta in Kohilawatte

Yet, there is a marked scarcity of livable or commercial land. And the search for more has worsened many Colombo’s flood problems, experts say. Urbanisation has been rapid. Surfaces which earlier absorbed water are now paved. Walls have come up, further blocking the ebb of water that overflows from the Kelani River.

River and canal banks as well as bunds have been encroached upon. The prerequisite for construction to take place at least 50 feet away from the river has been flouted everywhere. “The land use pattern has changed,” said an official from the Metro Colombo Urban Development Project (MCUDP), requesting anonymity. “There are a lot of impervious areas so infiltration of water into the soil is less. Eighty percent of water is overland flow that suddenly reaches the canals.”

B.B. Arunddhika, Pahala Bomiriya Grama Niladhari

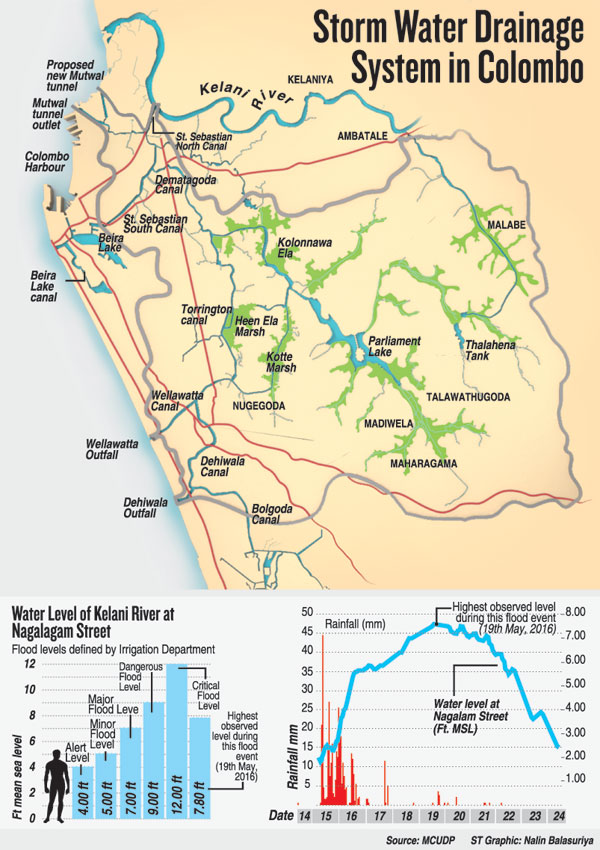

“Storage capacity within the metro Colombo area is also limited at just 39 percent,” she continued. The five existing canal outfalls (three to the sea and two to the Kelani River) can drain around 26 percent of water but the balance 35 percent contributes to flooding. There are 45 flood-prone areas within the Colombo Municipal Council limits.”

There are plans under the World Bank-funded MCUDP to reduce flooding. While the project kicked off in 2012, much time was spent carrying out research — such as a wetlands study and a rainfall study — and laying the groundwork. Tenders will soon be called for the building of new tunnels leading to sea outfalls and a pumping station is envisaged at Nagalagam Street to draw and discharge flood waters as they occur.

The Irrigation Department has identified other measures that need to be taken on short and long-term basis, Irrigation Director General S.S.L. Weerasinghe said. But there are challenges. Chief among these is the need to relocate and compensate thousands of unauthorised dwellers. A large sum of money will be required for development and upgrading of flood mitigation measures. And, unfortunately, the sense of urgency that follows the occurrence of a major flood almost inevitably fades away with time.

Nevertheless, among the short-term steps the Irrigation Department hopes to take is the removal of unauthorised dwellers, especially in highly vulnerable areas; control of land reclamation; and the improvement of existing flood protection structures such as Kelani River bunds.

| Frequent flash floods predicted: Building reservoirs a way outThe trend now is for large rainfalls of high intensity to occur at faster frequency, causing flash floods, Prof. S.B. Weerakoon of the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Peradeniya said. He is an expert in river hydraulics.Along with others, Prof. Weerakoon has studied long-term climate impacts and trends in rainfall variation. His team has also developed a two-dimensional inundation model downstream of the Kelani River to predict how water flows below Hanwella. While annual rainfall figures have not shown a significant difference, extreme events are expected such as periods of drought followed by heavy precipitation. “More frequent flash floods can be expected while disasters and magnitude of damage will be more,” he said. As sea levels rise, drainage of flood water to the sea will be delayed. The authorities must turn their attention towards people living in flood plains with a view to reducing disaster, he stressed. As floods impede economic development and require large outlays to fix the damage, the State must divert resources towards prevention. There was no one solution, Prof. Weerakoon explained. “Our thinking is that storage improvement or reservoirs in the upper catchment areas is the best option, as much as possible,” he explained. Pumping stations were welcome but were dependent on electricity, which might fail. They also needed maintenance and repair. Expanding the river canal system and river mouths to push water out to sea are other options. The capacity to absorb flash floods has gone down tremendously with the reduction of wetlands over the years, said Prof. Devaka Weerakoon, a renowned wetlands specialist. Wetlands in Kelaniya and Dematagoda — most marshes are situated in valleys — have been converted to settlements. This meant capacity was reduced where it was required most. Weaknesses in existing drainage system, impediments to river flow, tanks being silted and conversion of wetlands all contributed towards eroding the ability to withstand flash floods in the Colombo metropolitan region. Prof. Weerakoon also observed a change in weather patterns leading to short periods of heavy rain. “What we’re suggesting is zero loss of wetland,” he asserted. “Let us make sure that we preserve the wetlands we have. They are still being converted, even with all this bad experience.” Other engineering interventions have been proposed to facilitate the flow of the river such as cleaning canals, raising bunds and eradicating bottlenecks. “But it is very important to maintain existing wetlands because engineering interventions alone cannot solve the problem,” he warned. “It is not a possible scenario.” Prof. Weerakoon said efforts must also be made to create new wetlands in abandoned lands to increase the buffer against floods. “This is the best time, when people feel it is important,” he warned. “When the flood goes down, it will be business as usual.” |