Sunday Times 2

Fragile states index: Whither Sri Lanka?

View(s):In 2015, long-simmering crises crossed borders, even continents, in a reminder that it takes very little for regional instability to go global.

This is particularly true when those who are caught in the fray of violence will stop at little to save themselves and their families. Turmoil from Syria to Nigeria spiraled outward last year, leading to unexpected consequences sometimes thousands of miles away from their point of origin.

For 12 years, the Fragile States Index (FSI), created by the Fund for Peace and published by Foreign Policy, has taken stock of the year’s events, using 12 social, economic, and political indicators to analyze how wars, peace accords, environmental calamities, and political movements have pushed countries toward stability or closer to the brink of collapse. The index then ranks the countries accordingly, from most fragile to least.

And in terms of the countries that became more fragile this year, there were perhaps few surprises. The Syrian civil war has been roiling the Middle East since 2011. But in 2015, spillover from the chaos finally hit Europe in the form of more than 1 million asylum-seekers who flooded into the continent. Their arrival sent Europe into a panic — and some previously stable countries were sent sliding up the ranks of the index.

Hungary and the other central European countries that line the so-called Balkan route from the Middle East to Europe saw a xenophobic backlash, often stoked by their own politicians, raising growing concerns about the state of human rights in these countries. The migrant crisis also played a role in the United Kingdom’s referendum on whether to leave the European Union. Those advocating that Britain go it alone often cited concerns about migration and the need for Britain to maintain control of its own borders. On June 23, in a stunning turn of events, the country voted to leave the European Union, sending global markets into a nosedive and leading to the resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron.

In West Africa, the Boko Haram insurgency has taken its toll across a wide swath of countries. Chad, Cameroon, and Niger last year saw their share of violence, and also of refugees fleeing the violence. Niger and Cameroon each hosted more than 100,000 people displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency by the end of the year — a reminder that, while news about the migration crisis in Europe makes headlines, the countries that bear most of the burden for hosting those displaced by instability are often the ones next door.

In West Africa, the Boko Haram insurgency has taken its toll across a wide swath of countries. Chad, Cameroon, and Niger last year saw their share of violence, and also of refugees fleeing the violence. Niger and Cameroon each hosted more than 100,000 people displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency by the end of the year — a reminder that, while news about the migration crisis in Europe makes headlines, the countries that bear most of the burden for hosting those displaced by instability are often the ones next door.

One bright spot in the index was long-suffering Sri Lanka: Sri Lankans in 2015 elected a reformist as their new prime minister, who has kicked off his tenure with measures to help soothe the country’s war wounds and speed ethnic reconciliation, making it this year’s most improved state.

Here’s how Fund for Peace saw how Sri Lanka changed in 2015:

SRI LANKA: MOVING AWAY FROM THE SHADOWS OF WAR

For Sri Lankans, 2015 began with a presidential election and hence a choice: to re-elect Mahinda Rajapaksa, the mercurial and nepotistic leader who put a bloody end to the country’s 26-year civil war in 2009, or to vote for Maithripala Sirisena, the self-effacing health minister, who — as J.S. Tissainayagam described in a January 2015 article — promised to “transform Sri Lanka from a near autocracy into a democracy.”

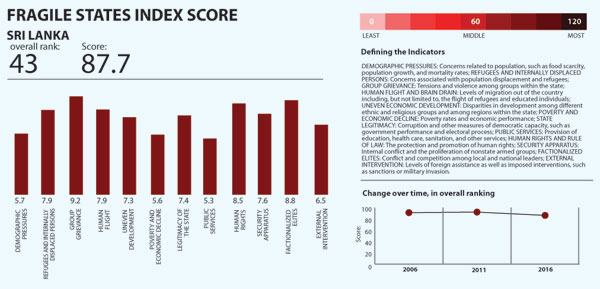

It’s likely that Sirisena’s surprise victory — just several months earlier, he had been a loyal member of Rajapaksa’s government — and his modest but important steps toward healing the nation’s war wounds are in large part why the island nation is this year’s most improved country on the Fragile States 2016 Index, moving nine spots in the rankings, from 34 to 43 in 2016.

Sri Lanka’s success this year is largely due to Sirisena’s victory, coupled with a reduction in natural disasters (devastating floods regularly hit the country; in 2011, incessant rains made homeless 200,000 people, or roughly 1 percent of Sri Lanka’s population). Since taking office, Sirisena has pushed for a new constitution that limits the power of the president’s office and put his country on the path to ethnic reconciliation. He has more successfully integrated the minority Tamils — the losers of the civil war — into the government and worked to create a special court to prosecute human rights abuses committed during the war. In a nutshell, Sirisena’s policies channel the Sri Lankan people’s desire for equality and integration; and his success in meeting the electorate’s needs is reflected in the country’s legitimacy score, which improved by 0.6 points from last year.

Despite its notable shift in this year’s rankings, Sri Lanka still falls in the High Warning category — and its score remains a worrying 87.7. And while the country has improved on most indicators over the past five years, the outlook for the Group Grievance and Human Rights categories, with scores of 9.2 and 8.5 respectively, remains especially concerning.

And while Sirisena has led his country on a path toward a more balanced form of government, the Fund views his administration’s tendency to reject outside support as a cause for concern. Sirisena, for example, has refused to allow international oversight for his human rights court. In response to the U.N.’s call for an investigation by foreign judges into abuses committed during the war, Sirisena responded that he would “never agree to international involvement in this matter.”

Still Sirisena and his people deserve credit for the country’s improvements over 2015. Though as Tissainayagam observed after Sirisena’s election, his country still faced many challenges — ethnic unity, corruption, and government reform, among others. For the time being, he wrote, Sri Lanka still needs to “hold the champagne.”

Courtesy Foreign Policy