Arts

Highs and lows: Channa retraces his steps

When Channa Wijewardena speaks, his hands betray him. They’re a dancer’s hands – never still, often gliding into emphatic gestures to highlight a point or better demonstrate an incident. His dance career began as a sporting enthusiast, skulking for dance classes between sports practices, hiding his interest in dance with a schoolboy shame that was shed later.

When Channa Wijewardena speaks, his hands betray him. They’re a dancer’s hands – never still, often gliding into emphatic gestures to highlight a point or better demonstrate an incident. His dance career began as a sporting enthusiast, skulking for dance classes between sports practices, hiding his interest in dance with a schoolboy shame that was shed later.

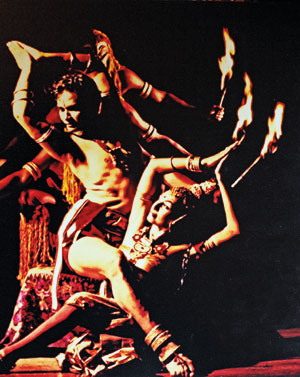

Upuli: Channa’s partner in dance and life

Today, Channa and his wife, Upuli, run The Channa Upuli Performing Arts Foundation and are proponents of a dance form which melds traditional Sri Lankan dance routines, contemporary dance discipline and a marketable glamour. The foundation teaches dance to 1000 students and has a troupe of over 30 professional dancers who also double up as instructors.

Currently, Upuli and Channa Wijewardena’s house in Dehiwala is one that is subsumed by dance. Performances are frozen on photographs and pack the walls and stairways or are propped on the floor. Drums and a mishmash of traditional instruments are heaped in a corner of the living room and are lent a curiously decorative air. Every day, you’re likely to find purple clad dancers around the house – a second home for them because of daily practices. The entire house, its inhabitants and its guests dance attendance around one room on one of the upper floors – a compact and well-lit studio with long mirrors and wooden floors with a strict no-phone policy.

The troupe have toured the world. Their most recent performance was to an audience of 5000 Sri Lankan expats and Americans in Houston, Texas. The foundation hopes to open its own dance studio in Colombo and also plans to open schools in Japan, Canada and Australia.

Channa’s initiation into dance came after watching a traditional dance performance on stage when he was a schoolboy. After rugger practices in school, Channa would go to pick his sister, Yamuna, from practices at the Chitrasenas. If she wasn’t ready by the time he came, he would settle down and watch the dancers practise with an idle but disengaged interest. He was asked by Guru Vajira Chitrasena to help sell souvenirs at a show and acquiesced. On the day of the show, he was nonplussed at the crowds and number of foreigners who had gathered to witness an evening of traditional dance.

On that night, the first stirrings for the art and the desire to dance was invoked within Channa. Perhaps it was the pull of theatricality and the magnetism of the stage but when Channa watched Guru Chitrasena perform that night at the YMBA Borella, something changed. Soon, he began to accompany his sister for dance practices at the Chitrasenas.

On that night, the first stirrings for the art and the desire to dance was invoked within Channa. Perhaps it was the pull of theatricality and the magnetism of the stage but when Channa watched Guru Chitrasena perform that night at the YMBA Borella, something changed. Soon, he began to accompany his sister for dance practices at the Chitrasenas.

Having studied traditional dance under Chitrasena, Channa branched off when he was 20 to study other forms of dance, including Indian and classical ballet. Years later, his first glimpse of his guru, Dr Chitrasena on stage that night still holds sway over Channa and his first dance teacher’s influence over his life is unmissable. “They’re the masters. No one can reach them,” he states categorically, reflecting on the Chitrasena troupe and their commitment to traditional dance and dance drama. “If we’re the stars, they’re the sun. Their whole life is dance.”

For traditional dance custodians, Channa’s permutations of traditional dance is seen as an adulteration of original traditional dance and a commercialization of the art. His career trajectory as a dancer and choreography is filled with critics who have lamented over the deterioration of traditional dance and a seeming dilution of its authenticity. Channa has made Sri Lankan dance relevant, but has it been done at the expense of the art? Over the years Channa has staunchly defended his art and is resolute about its roots, explaining that at its core is Sri Lankan traditional dance, enriched by the theatrical discipline of varying techniques and dance styles.

It seems apt to take stock of Sri Lankan traditional dance as it stands today and assess its rejuvenation and mutations. Many of Sri Lanka’s traditional dance forms are rooted in rituals and ceremonies, which later took on a life of their own as an art. Heavy from a colonial hangover, local audiences were unconvinced of initial attempts to link traditional dance with theatre during the early years of reviving traditional dance. Women as professional dancers were rare. Dance dramas – Sinhala ballets which narrate stories through dance – were looked on with scepticism. Writing reflecting on the revival of traditional dance detail accounts of meagre media attention, disgruntled audiences and cynicism, before traditional dance as we know it today, was finally acknowledged as a high art form.

If Chitrasena transformed traditional dance and resuscitated indigenous techniques through innovation, it may be apt to credit Channa for nudging traditional dance into the mainstream. Under Channa’s hands, traditional dance is dismantled into key techniques while retaining the crux of the art form. In one performance for example, there’s an irreverent insertion of a basketball jump woven into the kasthirama adauwwa. It is visually packaged differently, making it easily consumable to mass audiences. There’s also a focus on the physicality of the dancer – not just on the dance itself – giving the dance a telegenic sensuality that is absent in traditional dance.

Renowned dancer and musician, Ravibandu Vidyapathy began classes at the Chitrasenas on the very same day as Channa and voices his gratitude for the firm foundation that Guru Vajira Chitrasena gave both of them in their formative years. He reminisces, noting that Guru Chitrasena identified Channa as being a lyrical dancer and himself, a dramatic dancer, and would cast them in ballets accordingly. “He [Channa] strikes the perfect balance between what one may call ‘commercial dance’ and ‘serious dance’” explains Ravibandu, acclaimed for his deep insight into traditional music and dance.

“In Channa’s work we see the perfect union of these two genres. I see this in his work – the elements of classical traditional dance being artistically extended and interpreted to reach a wider audience of dance lovers of different social strata.” He notes that Channa’s wide knowledge of various technological aspects of today – from lighting and sound to the wide arc of make-up and costume design – are perfectly woven into his unique style of choreography.

This brand of dance has seeped into popular culture. Traditional dance troupes during weddings are a familiar fixture. Channa makes an interesting point about fire and the goddess poses incorporated in wedding dances, commenting that they are believed to ward off evil spirits for the newly married couple – a modernization of the ritualistic elements which first prompted dance traditions. In pop songs and musical concerts, traditional dancing accompanying the singing has become ubiquitous, while multiple traditional dance troupes have mushroomed in the last two decades.

Channa recalls an incident which occurred years ago when the criticism was at its zenith. A troubled Channa had approached his old guru, Chitrasena, in despair, ready to give up. Chitrasena had used a sports anecdote to help Channa reflect. “You used to play rugger – when are you tackled?” he asked. “When you have the ball,” replied Channa. “What do you do, if you don’t want to be tackled?” he asked again. “You pass the ball.” “You have the ball now. If you don’t want to be tackled, just pass the ball,” the master replied.

There’s plenty to fuel the debate between high art and popular art (a common academic tussle within all aspects of the arts) but it’s important to acknowledge that each feeds interest into the other. There’s also an intellectual curiosity about tradition and dance discipline in popular art which are glossed over as a result of its commercialization.

Amidst the debates there are two things which Channa remains firm about. The first is that before a dancer walks onto the stage and assumes their stance, he/she has to earn it first through hard work. There are no short cuts and quick fixes to becoming a dancer. The other is the overarching influence of Upuli, on his art.

When the Sunday Times met the couple two weeks ago, it was their 25th wedding anniversary. Bouquets of flowers from students and well-wishers were interspersed with the dance paraphernalia in their living room. Behind Upuli was an enlarged photograph of the couple enacting Radha and Krishna in a dance. The two met at a performance of ‘Sri Sangabo’ which was set to tour China and appeared on stage together regularly during their early dancing days. Channa vows that Upuli is his best critic and attributes his success to her.

Upuli, the daughter of Guru S. Panibharatha, comes from a traditional dancing heritage, and has been dancing since she was four. Thanks to her father, Upuli grew up to the soundtrack of the dull thud of dancing feet and the constant beat of drums pervading her house. Although Upuli is now away from the stage, their dance-chemistry spills over into real life. Upuli mediates with the world- translating Channa’s concepts, intuitively knowing what he wants in terms of costume or pausing to give the occasional direction. “I still think I haven’t danced enough though,” smiles Upuli, who now takes on a managerial role, explaining that the feeling of being on stage was one that escapes the confines of language.

On the day of the interview, the studio is filled with young dancers incorporating elements of the Laban technique – championed by movement theorist and choreographer, Rudolf Laban – and the Horton technique into their choreography. Quotidian activities such as sweeping, mining for gems and clearing cobwebs are lent an air of grace and transformed into dance.

Channa, clad in white, issues rapid-fire instructions and watches them carefully with the stern eye of a teacher. The dancers break into clusters and demonstrate each activity first, then incorporating them into dance movements while the rest chant the beat.

The last cluster of dancers fuse the movement of washing clothes into their steps. When they finish, Channa nods his head in approval, and the dancers retreat to the sidelines.