News

Lanka wins battle against Filariasis long before the global date of 2020

View(s):Success story recognised at a ceremony in Colombo graced by WHO

South-East Asia Regional Director Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

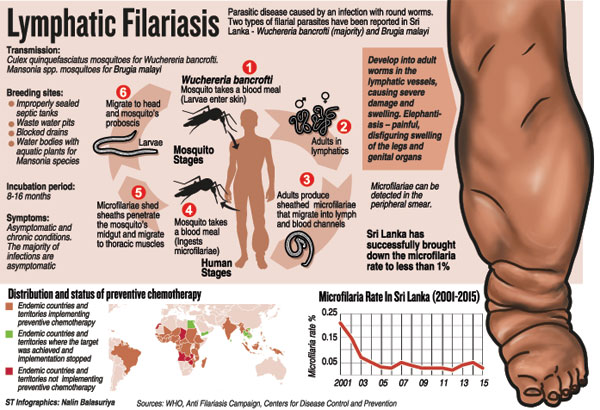

Footprints on the sands of time – initially left by a pair of feet, one thin and the other huge and disfigured, gradually washed away by the foamy waves to be followed by another pair of normal feet. This video succinctly encapsulated Sri Lanka’s success story with regard to elephantiasis or as it is known medically Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) on Friday.

WHO SEAR Regional Director Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh presents the Certificate on Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis to Health Minister Dr. Rajitha Senaratne, as (from left) Anti-Filaria Campaign Director Dr. Devika Mendis, Health Ministry Secretary Anura Jayawickrama, Health Services Director-General Dr. Palitha Mahipala, WHO Representative to Sri Lanka Dr. Jacob Kumaresan and Deputy Director-General of Public Health Services, Dr. Sarath Amunugama look on

The accolades were many for Sri Lanka as it is just one of two among the nine LF endemic countries in the South-East Asia Region (SEAR) of the World Health Organization (WHO) to gain Certification on the Elimination of LF. (The other country is the Maldives.) With Sri Lanka currently in the vice-like grip of the dengue-spreading mosquitoes, the victory over the LF-bearing mosquitoes is cause for celebration.

It was none other than the Regional Director of SEAR, Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh, who presented the plaque to Health Minister Dr. Rajitha Senaratne at a brief ceremony which went like clockwork on Thursday at the BMICH. A commendable feature of this ceremony was that not only the current Director of the Anti-Filariasis Campaign (AFC), Dr. Devika Mendis, and her team but also those who had waged war on this disease before them, were celebrated on Thursday.

“The WHO declared Sri Lanka as the first country in SEAR to fulfil the criteria for eligibility to secure the Certificate of Elimination in April 2011,” said Dr. Mendis with a touch of justifiable pride. Casting light on the local ‘picture’ of barawa as LF is called by the people, Dr. Mendis said that it is endemic in eight districts in the Western, Southern and North Western Provinces which have around 50% of the country’s population.

Environmental conditions conducive to vector breeding, unplanned urbanization and a high population density have aided the spread of LF in the districts of Kurunegala, Puttalam, Galle, Hambantota, Matara, Colombo, Gampaha and Kalutara, it is learnt.

The stringent control strategies leading to successful elimination, according Dr. Mendis, have been parasitological surveillance and control (night blood surveys for case detection and treatment); Mass Drug Administration (MDA) programmes; vector surveillance and control (assessment of disease transmission, elimination of breeding places and use of integrated vector control methods); and morbidity or disease management and disability prevention.

Not content to rest on their laurels, the AFC assured the continuation of surveillance in endemic areas, conduct of surveys in non-endemic areas, enhancement of morbidity management and control of transmission by parasite and vector control.

Not content to rest on their laurels, the AFC assured the continuation of surveillance in endemic areas, conduct of surveys in non-endemic areas, enhancement of morbidity management and control of transmission by parasite and vector control.

“This is to achieve our vision of ‘a Filariasis-free Sri Lanka’,” added Dr. Mendis.

While both Minister Senaratne and Dr. Singh commended the staff for this major public health victory, Dr. Singh held up Sri Lanka as “a beacon of hope” to other countries struggling under LF’s burden as well as other Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), the control, elimination and eradication of which are very close to her heart.

Quoting the shocking figure of 1.1 billion people in 55 countries being threatened by this disease and more than 120 million people estimated to be suffering from chronic forms of LF, though not fatal “disfigures and disables, stigmatizes and impoverishes”, she reiterated that Sri Lanka’s achievement demonstrates that it can be eliminated. The key to elimination is strong political commitment and effective deployment of evidence-based strategies.

Sri Lanka’s achievement underscores that LF is a disease that should have no place in today’s world, said Dr. Singh.

Pointing out that Sri Lanka’s campaign against LF began in 1947 and it was the first time that Sri Lanka and the WHO worked together in the area of disease control, she paid tribute to the health authorities for their concerted efforts in lifting its burden from vulnerable communities across the country. “This is a true reflection of the strong commitment of the government to improve the health of its people, particularly the most marginalized.”

Dr. Singh brought under the microscope how Sri Lanka has been able to achieve elimination long before the global target of 2020 – with the country’s most recent elimination programme being launched in 2002. The ‘key interventions’ have been the scaling up of vector control efforts; intensification of case detection and treatment; strengthening of surveillance systems; rolling out of a mass drug administration (MDA) campaign; and ensuring community engagement and active participation.

LF is one of many health milestones Sri Lanka has achieved and the WHO Regional Director referred to how the country stopped the poliovirus transmission way back in 1995 and has continued efforts to remain polio-free by keeping strict vigil against polio virus importation and maintaining high population immunity through the childhood immunization programme. The leprosy elimination target at national level was reached in 1999, while indigenous malaria transmission was halted in 2012, with the country set to achieve malaria-free status soon.

While lauding the leadership for innovative initiatives, Dr. Singh gave timely warning of the current public health challenge of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). “The strong public health workforce and grassroots infrastructure that have won several battles against communicable diseases is now geared towards addressing the prevention and treatment of NCDs. I am confident that their demonstration of successes will lead the region in facing these new and emerging challenges,” she said, adding that Sri Lanka’s health system is the “envy” of countries, both rich and poor, across the world. The WHO was proud to be a credible and trusted partner in the country’s ongoing public health mission.

But, Dr. Singh was quick to point out the ‘unfinished agenda’ as well as upcoming challenges such as Zika Virus, MERS Corona Virus and Yellow Fever and how best to tackle them. “It is critical that countries prioritize and invest in complying with the International Health Regulations (IHR) and achieve core IHR capacities,” she said while appreciating Sri Lanka’s progress in this regard and looking forward to further growth in the future.

The distinguished gathering at Thursday’s celebration included WHO Representative to Sri Lanka, Dr. Jacob Kumaresan; Health Ministry Secretary Anura Jayawickrama; and Health Services Director-General Dr. Palitha Mahipala. The apt video showcased before the event had been produced by Dr. Kapila Sooriyaarachchi of the Health Education Bureau.

| Crucial to maintain success of ‘elimination’ It is crucial to maintain the success of the ‘elimination’ status of Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) and prevent its resurgence through diligent control measures, the WHO Representative to Sri Lanka, Dr. Jacob Kumaresan told the Sunday Times. Of the 11 countries which form the WHO South-East Asia Region, nine are endemic for LF and two are non-endemic. While Bhutan and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea are non-endemic, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand and Timor-Leste are endemic. Tracing Sri Lanka’s public health epidemiological transition from infectious or communicable diseases (CDs) to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), Dr. Kumaresan says that there has been good control of CDs, several of which are currently in the stages of elimination and eradication. What is causing major problems are NCDs. Before dealing with Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) that Sri Lanka is confronted with, he defines them as a diverse group of CDs that prevail in tropical and sub-tropical conditions. These NTDs are found in 149 countries, affecting more than a billion people. While costing the economies of developing countries billions of dollars annually, NTDs mainly affect impoverished populations, living without adequate sanitation and in close contact with infectious vectors and domestic animals and livestock, he points out. The major NTDs confronting Sri Lanka are LF, dengue, malaria, leprosy and rabies, it is learnt. Elimination denotes the achievement of very low levels of disease transmission in the country. But achieving zero transmission is not feasible due to the continued existence of the bacteria, virus or parasite in the environment. Here he cites the presence of the parasite and the vector mosquito in the environment in both LF and malaria. Eradication, meanwhile, means getting rid of the whole problem like in the case of small pox. The challenges that Sri Lanka faces in the future with regard to LF, meanwhile, would be managing the few remaining ‘hotspots’, monitoring and detection of the non-primary but abundant Brugia malayi parasite and not allowing the focus on LF to be distracted by dengue. With the WHO’s 2020 Roadmap on NTDs on the table, Dr. Kumaresan says that many of these diseases can be controlled by the end of the decade. However, this cannot be done alone. There is ‘power in partnerships’ and different stakeholders including the affected people themselves should get-together to overcome NTDs. | |