Blast from the past

View(s):Many of us have forgotten a time when bomb blasts and suicide attacks were part of our lives in Sri Lanka. Today, it’s 20 years since one such attack, the Dehiwela double bomb blasts ripped apart a train and families. Kumudini Hettiarachchi talks to some of those who lost their loved ones and survivors, who all believe in the power of reconciliation in spite of their deep pain

It was a routine train ride and in the blink of an eye, a blast leaving numerous lives shattered – some dead and others severely injured, the innocent victims of a futile war. As July 24 dawns, in many a home close to the southern railway snaking between the turquoise blue ocean and towns dotting the landscape there will be memories, tears and anguish.

It was a routine train ride and in the blink of an eye, a blast leaving numerous lives shattered – some dead and others severely injured, the innocent victims of a futile war. As July 24 dawns, in many a home close to the southern railway snaking between the turquoise blue ocean and towns dotting the landscape there will be memories, tears and anguish.

Twenty long years may have passed, but for those who survived to tell the tale of horror and carnage those memories are acute, the day’s events vivid and seared into their psyche just like yesterday.

“Were they bad omens,” wonders Rosie Peiris as she and her husband, Sirimal, gaze with sadness at the large black-and-white photograph of their handsome son, Samadhi.

Like in any household on a weekday morning that fateful Wednesday in July 1996 was rushed in their home in Moratuwa. Having prepared breakfast and also lunch, Rosie was the first to leave home. As Samadhi was still asleep, she knocked on his room door, said “Bye Babee and God bless” and rushed to catch the train to Fort where she was working in the Bank of Ceylon (BoC) subsidiary, Property Development Ltd.

When she disembarked at the Secretariat Halt in Fort between Hilton Hotel and BoC Headquarters, she was met by a heavy shower that snapped her umbrella in two, forcing her to seek shelter in the Hilton Hotel car park. On reaching office, she called Samadhi who laughingly told her, “Mama wessa yatin giya” (I went under the rain), while she promised him that she would buy two umbrellas, one for herself and one for him.

As their one and only son, he was very close to them, says Rosie. He would share anything and everything with them. He played the fool with them often and loved to tickle her, knowing her reaction. Just five days before July 24, 1996, he did just that and as they joked around in his room his bed collapsed. They did not give it a second thought.

That morning in July, Sirimal was able to wave goodbye to Samadhi as he was leaving home for work at a travel agency in Kollupitiya. What this tiny family did not know was that their lives would change forever that very same evening. Where there were three only two would be left behind, along with a gnawing ache of loneliness.

That morning in July, Sirimal was able to wave goodbye to Samadhi as he was leaving home for work at a travel agency in Kollupitiya. What this tiny family did not know was that their lives would change forever that very same evening. Where there were three only two would be left behind, along with a gnawing ache of loneliness.

“Rosie came in the 5.45 evening train back home, Samadhi took the next one and I came in the third,” says Sirimal with a tinge of sadness…….and the bombs were in that middle train. It was just as Rosie was putting on the kettle to make herself a cup of tea that the call came that there had been a bomb on a train at Dehiwela. Knowing that Sirimal was getting late that day, Rosie was frantic, for where was Samadhi. Those were the days sans mobile phones and as she rushed to the Moratuwa Railway Station she was met by a “sea of heads” with everyone running here and there. The land phones were also jammed.

Samadhi: Son of Rosie and Sirimal (above right)

The search for Samadhi, at one hospital then another ended the next morning, around 2, when at the Kalubowila Hospital, a stranger asked them whom they were looking for and told them that he had carried a youth with a “geta, geta muddak” (a rosary ring) into the mortuary.

The search for Samadhi, at one hospital then another ended the next morning, around 2, when at the Kalubowila Hospital, a stranger asked them whom they were looking for and told them that he had carried a youth with a “geta, geta muddak” (a rosary ring) into the mortuary.

It was much later that people pieced together the few hours of Samadhi’s life. He and a friend arrived at the Kollupitiya Railway Station together when the packed Aluthgama-bound train pulled in. While his friend decided not to board it, Samadhi did and as the train left the platform indicated to her with his hands that he was rushing home to give tuition to underprivileged children in the area, part of much voluntary work that he was engaged in through an organization called ‘Yovun Handak’ (Voice of Youth). When the train reached Dehiwela, there was panic as passengers were told to disembark after the discovery of a bomb, which was later defused. On returning to the compartment, Samadhi was able to secure a seat but offered it to a girl and while standing up tapped a briefcase on the rack and joked whether it could be a bomb. It was.

Along with another one, the bombs exploded moments thereafter.

The girl to whom Samadhi gave his seat survived with very severe injuries.

“There is never a moment when I don’t think of him. When he was schooling, in the evening he would come to the railway station to pick me up and take me home on his bicycle. Sometimes he would also keep the rice to boil and make a dhal curry knowing that I would be tired,” whispers Rosie overcome by emotion. She and her son loved music and listened to the radio together often and after his death for five years she was unable to switch on the radio. There was only the sound of silence in her life.

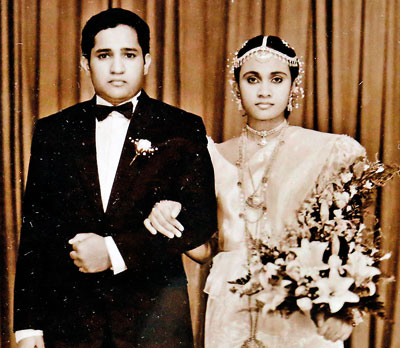

Bede and Lidwina on their wedding day

He was very concerned about the beach children and told her they were writing the notes of all eight subjects in one book. So he collected money to buy books for them, she says, while Sirimal talks of Samadhi’s political vision and his writings on the need for unity.

After the tragedy, Samadhi’s loss was eating into their very being, there were tears, weeping and wailing and everyone suggested that they have another baby. Now that baby is 19 years old and there are two photographs side-by-side taking pride of place in their current home in Mount Lavinia – one of Wismitha and the other of Samadhi, the brother he never knew.

“That day’s terror has nothing to do with innocent Tamils. War and terrorism are futile and there has to be a political solution to the Tamil grievances to ensure that what happened to our son will never happen to anyone else,” says Sirimal.

Rosie and Sirimal brought home their son and buried him amidst prayers and tears, but sadly Lidwina Sebastian never got a chance to bid adieu to her beloved husband, Bede.

The memories flow forth along with sighs, as she recalls how she and her husband boarded the train at the Secretariat Halt that evening, while their seven-year-old son, Stefhan eagerly awaited their return at home in Panadura. Lidwina was working at the Galadari Hotel and Bede at the Commercial Bank Head Office.

As they walked down the stairs to the platform, a train arrived but Bede suggested that they go in the next. The plan was for the couple to do their grocery shopping after de-training at their destination. “It was crowded,” says Lidwina, who with Bede boarded the one-but-last compartment. There were murmurs when the train stopped at Dehiwela, for the same thing had happened in the morning at Wellawatte and the commuters assumed it was something to do with the signals.

She and Bede were close to the compartment’s landside door and Bede standing tall above the tightly-packed crowd was reading the newspaper that she had given him. A blast followed by dead silence…….then many voices. Lidwina could not move her hands and legs. There were splinters in her eyes, her ears were humming and through a haze she saw a pink head falling on her. “I tried to shout but no voice came,” she says, as she wept to be saved.

Indika

Help did come later, with people lifting her onto a gunny and sending her in a vehicle to the Kalubowila Hospital. It was here that she realized that her whole body was burnt and black and the bomb had ripped the clothes off her and a nurse covered her up. She was once again put on a stretcher and sent in a small van to the National Hospital.

Some memories are distinct, a reporter talking to her to whom she gave her aunt’s number, but the message was never conveyed. It was the next day that Bede’s best friend’s mother tracked her down and made arrangements to transfer her to a private hospital, which she believes saved her life.

To all her entreaties for news about Bede from relatives there was only silence. What they did not tell her at that time was that Bede had been the first to be taken to the mortuary having got the full blast of the explosion due to his height and that they had already buried him. His only evident injuries had been a small scratch on his face and a broken hand.

Indika and with Lasantha on the day of their marriage

It has been a long road to recovery for Lidwina with 32 stitches on her head, hearing loss in her right ear and her left ear having to be reconstructed through painful operations. Up to now she walks around with shrapnel in her body, due to which she would never be able to have Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a medical test or walk through security machines without them beeping. The scars have not only been physical but also psychological, for until recently she has shied away from trains.

This ordeal, however, has not deterred her from her husband’s goal of educating their son. Through trauma and travail, Lidwina (who lost her mother just before her wedding, suffered the agony of two miscarriages, then faced the death of her husband while suffering serious injuries herself and finally saw the home she and Bede had begun building with a bank loan before his death being caught up in the swirling waves of the tsunami) has been able to achieve this, while the Commercial Bank has established the Bede Sebastian Centre for Education and Research in memory of her husband who was the President of the All Ceylon Bank Employees’ Union at the time the cruel hand of fate snatched him away.

There is a sense of stoic resignation as she says, “Life has to go on.” (For a story by Bede and Lidwina’s son, please see bleow)

Another couple on that doomed train was newly-weds Indika and Lasantha Wickramasinghe. Married a month and 20 days, unlike many others, they were not regular train travellers. Living in Panadura, they would go to work by motorcycle but traffic congestion was a deterrent.

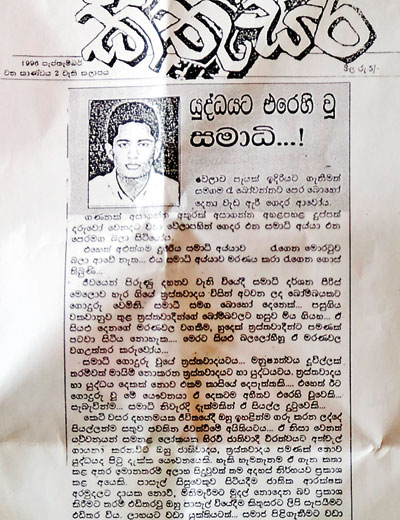

A young man who stood for justice: A newspaper article by Samadhi

Lasantha would board the one-before-the-last compartment of the train at Fort, as she was working at the Commercial Bank Head Office and he would join her in Wellawatte after finishing his duties at the Commercial Bank there.

Vividly he recalls how an earlier train got cancelled and when the power-set arrived it was jam-packed with people. At Dehiwela there was an unusual delay and talk of a bomb and as he desperately walked down the length of the compartments peering into the crowds, he saw her peeping from a window. The train began moving then and he hung onto the compartment.

“That’s all I remember,” says Indika who in the instant of the blast lost consciousness. Now living in Wadduwa, the memories seem painful even 20 years later – he could not open his eyes, his face was burning, his hair was burnt, he had no clothes on except his shirt collar, belt and underwear. When he woke up at the National Hospital in Colombo he was tied up for he had been struggling violently. Three of the fingers of his left hand had fallen victim to the bomb and had to be amputated.

He found his wife only three days later severely disfigured. She was blind in one eye, her lower jaw had been blown off, the rehabilitation of which is still being done two decades later. “My wife suffered 99% disfigurement and underwent 26 operations between 1996 and 1999,” he says.

Little wisps of memories come to the fore of several soldiers seriously injured in a blast in Mullaitivu helping other patients in the National Hospital ward and of an old Tamil man on the next bed who spoke not a word of Sinhala or English who would gently rearrange his sheet whenever it went awry.

Later, when he needed finger-reconstruction in India he would be warmly welcomed and looked after in Madurai by a Tamil family who had fled Sri Lanka after the 1983 riots ironically in July too. For Indika and his family, the blast brought about an entirely different dimension. “We don’t make many plans for the future, we live for the day,” he says with emotion.

Sriyan

It is a similar tale that we hear from Sriyan Fernando who was then working at the Commercial Bank Head Office. Excited about an outstation trip with the family the next day, he got off early from work and boarded the packed power-set. “When the bomb went off there was pandemonium and I was among the dead,” he says. “It was marila negitta wage (I had risen from the dead). It was a miracle.”

The only possession he had soon after the blast was the rosary he had always carried in his pocket since childhood and his underwear. First taken to Kalubowila Hospital and then to National Hospital, even his wife had not been able to recognize this blackened bloated man, with a huge bandage on his head, until he weakly waved at her. A deep gash in his head needed 27 stitches and he too could not sight a train for six months.

He relives a chance meeting with some Tiger women soldiers much later during a family trip to Madhu Church. As he pointed out the injuries he had suffered from the train blast, one woman had opened her blouse and shown him major scars left behind by a grenade blast on her chest which had also taken away her femininity.

Exactly two decades after that train explosion, there is hope arising from the wreckage and the debris – with each and every one elaborating on the need for reconciliation and restoration of justice among all races which call Sri Lanka home.

As much as the memories of these victims will make us remember that train of terror, like the phoenix, strong hope for a united Sri Lanka rises from such terrible tragedies……..hope of innocent people that cannot be quelled by extremists on any side.

| A story of war: A story of a boy and a girlBy Stefhan SebastianSo. I’m going to tell you a story. A story that you have heard before, it’s about your uncle, about your sister, about a friend of a man you used to work with. Sometimes it’s about your neighbours’ relatives from out of town and sometimes it’s about your best friend’s ex-girlfriend. You could say it’s about Sri Lanka and everything that we are. You could say it’s about nothing. But mostly, it’s about a boy and a girl. The boy liked to play basketball and listen to music. He had a collection of 8-track cassettes, some that he bought and others that he made by recording the songs on the radio onto blank tapes. He dreamed of being a doctor but didn’t have the grades and so he went into finance. The girl liked to sew and would teach children how to draw. She liked to go to the movies and take long walks, and started working in a hotel while deciding that starting a family was the only thing she really wanted to do with her life. The girl went to church and the boy went to the same church but didn’t participate; some type of personal protest against the biblical veracity of catholic esotericism. They met, and they started dating. They lied to their parents and went to the beach, and parks, and botanical gardens out of town, and to the movies. The boy held the girl’s hand in the movie theatre and asked if she loved him, and said that he did too. They got serious. They met each others’ parents, they decided to get married. A small group of rebels ambushed and killed an Army patrol over something they called independence and the Army called secession. Most people were upset, some people were angry and others assigned blame. The loudest part of that blame fell on Tamil people. So the boy’s family hid with their neighbours while their house was burned down and he didn’t come home for a while. They were burning his friends and people who shared his accent in the street, so he hid in the church, and found a way to call the girl. The girl was worried, she met with his family and helped to move them to an Air Force base. She waited for him. He came to her home when he felt it was safer to travel, they had lunch and made small talk. He told her that they should break up or they would always have to live like this, and after he left, her parents said the same thing. She said she was ready for whatever a life like this would bring, and that the only horror she feared was a life without him. Her mom got sick. They got married a month after they buried her. Everything changed after that. That small rebel outfit was now one of the largest separatist terrorist organizations in the world. The country was at war. There were intermittent curfews imposed at night, and bombings became a part of life. The boy and girl decided they wanted to have children. The first two died in the womb. The doctor decided that the third one would be delivered prematurely to ensure a greater chance of survival. So on Christmas eve he operated on her while the curfew was lifted, and their child was delivered on Christmas morning. The couple enjoyed being parents, but it was hard. He worked late and she worked weekends. They moved into a house near the beach, their son got older. Then the president was killed. Sometimes the police would search people’s homes for weapons and bombs, they would search the couple’s home often. Perhaps they felt the boy was a threat? The couple worked right next door to each other, but started travelling home separately. That way if one of them was killed, their son still wouldn’t have to grow up an orphan. But they were still in love and would make an exception for Wednesdays, and come home early, together, so that the three of them could have dinner together in the middle of the week as families like to. One Wednesday they got late, at first just late for a Wednesday, then just late. Their son was worried, but finally he went to sleep. His father’s brothers and sisters picked him up late that night and took him to his grandparents’ home. He saw his father a few days later. He was lying in a coffin. He was in one piece but his face was marred, not so much that didn’t know who he was, but enough that you knew he wasn’t anything alive anymore. He saw his mother a month after he buried his father. That was when she was moved out of intensive care. She was different, but in many ways that mattered she was still the same. She was never quite at peace with the fact that she couldn’t be there when her husband was buried. Everything changed, again. See stories of boys and girls are not apt to hold the horrors of war, and yet every story of war is a story of a boy or a girl. Written in the blood of this boy, the tears of this girl and many more forgotten like them. The dead disappear, but their shadows remain and reverberate through our lives. They’re that nagging sensation inside of you that no matter how good everything seems, something is very wrong but you’re just not sure what. | |