Ajit Gunewardene’s art of living a dream

View(s):

Explaining the urn he bought from a local market. Pix by Amila Gamage

KOSGODA – Ajit Gunewardene is refreshingly frank. Early in our conversation, he admits he is quite useless as an artist. This comes as no surprise for what I can recollect from school days is that he was a tough-as-nails rugby flanker at Royal whose ferocious cover tackling left many opponents dazed and wondering what they had run into. But the idea of the transformation from dashing rugby hard man to suave art connoisseur is still percolating through my mind as I’m greeted by Gunewardene at his enchanting getaway in Kosgoda, a hideout where he has on display numerous pieces collected over the years.

“I can’t draw a straight line. This is just something that grew on me,” reveals Gunewardene as he shows me around his collection. The five bedroom villa built by architect Channa Daswatte is overflowing with riches, some artefacts dating back centuries to the Dutch and Portuguese eras, many others made in Sri Lanka. While most corporate big shots – he is deputy chairman of John Keells Holdings – take pride in collecting cars or fine wines, Gunewardene is happy to let his eye rove over pieces of art, some of whose beauty is plainly clear only to the beholder – himself. “It has to catch my eye. It needs to stand out,” explains the hard-nosed businessman.

“Ultimately it is what you like. I’m not an art dealer. I collect and I do it with passion. Everything I have I am happy to hang on a wall. It becomes more than a collection and you want to appreciate it and live with it.” Art is big business. Hundreds of millions of dollars exchange hands as art aficionados drool over a Picasso or a Rembrandt. Not the case for Gunewardene who is a devoted buff of homegrown talent and is on a mission to give budding artists a voice. “I was introduced to art by my parents at a very young age. They travelled overseas visiting the museums of the world and I was fortunate enough to go with them as well as be interacting with people who loved art quite early in my life. It grew on me.”

Dad opens doors

Dad opens doors

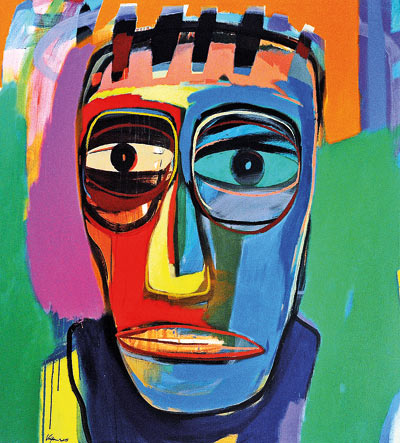

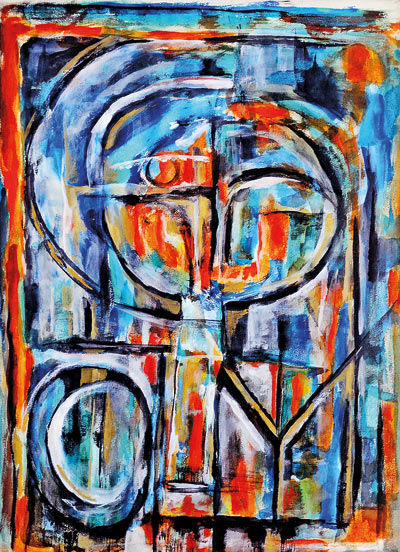

His dad, Norman, was then the chairman of Aitken Spence. It opened doors for the son who rubbed shoulders with the likes of Geoffrey Bawa whose influence was seen in a number of hotels owned by the group. Bawa’s presence also helped kindle the young Gunewardene’s nascent passion in art. “I began going for exhibitions and got interested in the ’43 Group and from that keenly followed our artists from the post-modernist era, the 90s Group, people who were influenced by what was happening in the country, the conflict, the war.” We move into a large and airy chamber where the walls are festooned with paintings. One whole section is lined with artefacts but the centre of attraction is a large metal figurative sculpture created by Pathmal Yahampath.

Gunewardene recounts: “I was taking a walk one evening and was passing Lionel Wendt where an exhibition was going on. I walked in and was immediately struck by two pieces from this young artist. They had a distinct style and I loved it. He brings movement into his pieces.” Fans of hit TV series Game Of Thrones will get an inkling of poetic sculpture which speaks volumes. The Iron throne which was forged from 1,000 swords – and which the seven kingdoms fight over in the bloody epic – reeks of power. Yahampath is more obsessed with the human figure and the piece standing in the Kosgoda drawing room is also powerful. It is mesmeric and casts a spell, one which is broken when Gunewardene pulls two books from a shelf and proclaims the contents belong to two of his favourite artists – Ivan Peries and Justin Daraniyagala.

’43 Group

’43 Group

This duo, along with George Keyt, was the core behind the ’43 Group. It is still early in the morning and the pages are turned as reverently as that of a prayer book. Gunewardene points to a Peries painting which he owns called The Beach. It is housed in his Colombo home. I try to decipher why he is going gaga over this monastic landscape but it is too much for my fuddled brain. Perhaps Yahampath and his metal figurine have flooded my cortex with an excessive dose of grandeur. But the imagination is fired up again when Gunewardene picks up a piece of pottery, or rather a lovely urn from a shelf. It was discovered in a flea market along the coast from where he lives.

“These are old urns found off the coast. They are from the 1700s and belonged to the Dutch East India Company. It was probably used to store vinegar or wine, or even rum. Perhaps the ship was sunk or maybe a drunken sailor threw it overboard after he had sipped the last drop from it.”

I’m transported back a few centuries. I can almost picture the scene – drunken sailors with urns of rum, possibly fighting over a wench, Keira Knightley a la Pirates of the Caribbean. The ship is tossed by a tempestuous storm and wrecked on hidden rocks.

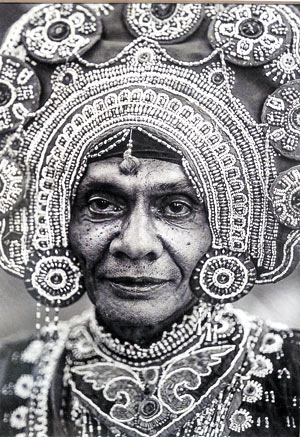

The only thing that survives is this one urn. The smell of the sea is overpowering and I feel I’m really in this picture before I realise that the winds are blowing in from the beach that straddles the private villa. All this art and artefacts before breakfast is quite heady. Each of the five bedrooms has a centerpiece painting. But it is an eclectic mix. There are pieces of batik from Ena de Silva, photographs by Kinglsey Gunatilleke and sculpture from Laki Senanayake.

Ena de Silva

Ena de Silva

A lovely hanging was delivered from Ena de Silva, just a week before the 93-year-old doyenne of batik passed away last year. It is mind-blowing to have been in touch with some of the greatest talents the country has produced. But it is not all about names and buying pieces from famous people. Gunewardene is quite Catholic in his taste and is a compulsive collector impetuously grabbing whatever catches his fancy. “I picked up this fabric which is more than 250 years old while trawling through Ambalangoda. I don’t know who made it, but these sorts of fabrics were used to cover the ceilings over the dining area so that stuff didn’t fall on you, things like rats and such,” says Gunewardene pointing to a large hanging overhead.

I’m not sure if he is joking about the rats but there is none to see in his villa which is named ‘Sihina’. It is indeed a dream walking through the house. Out in the garden are three walls plastered with the sculpture of Laki Senanayake. Each wall is made up of around a hundred individual tiles decorated with leaves and vines. You don’t know where one begins and ends for it is cleverly designed to depict a continuous flow. It is too much to partake of in such a short interview. The senses are overwhelmed with all these delights. It is probably best to savour it with a glass of amber nectar in one’s hand, something he does after he religiously goes for a beach run or a gym workout. No wonder Gunewardene retreats to this hideaway almost every weekend. He even holds brainstorming meetings with his staff at this dreamhouse.

Inspired thoughts

If his people are not inspired by what is on offer, then they surely must come from that breed of barbarians which sacked Rome. But JKH which prides itself as being a bastion where teamwork is given pride of place must surely have benefited for as Gunewardene points out a visit to his home “gives one perspective”. He laughs when I ask if he built Sihina to accommodate his art collection or if it was the other way around. His house in Colombo is also filled with art. “One influenced the other,” says Gunewardene. “But yes, I built this place to accommodate the other. My wife Chandani enjoys it thoroughly.

“But the point I’m trying to make is that there shouldn’t be only work in your life. Of course without work I wouldn’t have been able to do all this. But there should be a fine balance in your life and work should not override your passion, or the other way around.” Gunewardene admits that whenever he can, he tries to find some time when travelling overseas to visit the art galleries of London and New York. He hopes one day Sri Lanka too can become a centre for artistic excellence. “There is huge talent in Sri Lanka. We need to bring it out, support the artists and expose them. We don’t have contemporary art galleries. Lionel Wendt hosts one-off shows.

We don’t have permanent art galleries,” is the cry from Gunewardene who is working with a group of people to try and establish such a venue on a non-profit basis. It could become a home for this country’s talented sculptors and artists who have to resort to using the pavements of the city to display their wares, and the annual Kala Pola – open air art fair – which coincidentally for the past decade has enjoyed the patronage and support of John Keells Holdings under its corporate social responsibility programme. “A lot of these guys need to get off the pavement that is when they start creating art, instead of just trying to work for a living. Lot of these artists give up and enter the mainstream because they need to earn money, so there is a gap. The question is how do we bridge this gap,” Gunewardene asks.

Selling art

Selling art

“I come from a business background and I think in terms of economics which ultimately is what solves problems. We need to give them an outlet where they will be exposed, some place where they can sell their art and keep it going.” “There is nothing wrong in selling art on the pavement, but how do you progress from there. A lot of people buy the pretty picture and plenty of our good artists go down this commercial route. I don’t blame them but we must also give them an opportunity to flourish. The fundamental need is to have a gallery for there is enough talent here to create an art culture.”

Gunewardene gives the thumbs up to people like Shanth Fernando (runs the Paradise Road Gallery Café) and his daughter Saskia, and Jagath Weerasinghe (Red Dot Gallery) have done a lot to help unveil contemporary artists. But there is still a lot to do. That is the goal of Gunewardene – to help give Sri Lankan artists a voice and presence internationally, and create a world-class art museum in the country. But that is life after retirement, and after he has completed his dream to learn the Shaolin art. “I have already identified this place. Three months in the wilderness and away from humans and come back a qualified Shaolin warrior”. We have heard of Shaolin soccer but not Shaolin artist. Who knows, then, one day, he might be able to draw a straight line.