Country and markets remain in psychological paralysis

Holidays provide space for introspection. An extended sabbatical from these pages has provided time to delve in to various aspects of political economy that hold the key to our future. Both markets and consumers in Sri Lanka are currently suffering buyers’ remorse. As most business leaders keep reminding me, ‘whatever you do, please don’t mention January 8’. The pulse from Sri Lanka is one of pessimism and mistrust in an administration that acts like hormone charged teenagers, not responsible adults. Confidence in a fickle world is the most prized possession for capital markets. While uncontrollable externalities – terrorism and natural disasters – are expected to unnerve investors, those of a government’s own creation are inexcusable. Taxes are announced and reneged. Investigations are announced and reneged.

Investments from China are denounced, until those from the ‘West’ are found to be non-existent, and unashamedly re-embrace China. What then should investors make out of the inconsistencies and gross incompetence of a government unravelling faster than a third day pitch at Galle? Bond investors can take heart and equity investors should look elsewhere. What matters to bond investors most is the ability and willingness of a government to collect taxes as they act as payments that are then diverted to you the lender. On that score Sri Lanka has always had a good record. The current government has shown that they will pass unpopular measures and find creative ways to delay elections if necessary to keep bond holders happy.

At the end of the day, as Greece and Spain bear witness, its popular electoral backlash that will destroy bond holders – on both coupon payments, but more importantly return of capital. Fears that bond holders will suffer as a result of balance of payment difficulties are misplaced. Only 15-20 per cent of total outstanding bonds can be held by foreign investors, who are generally the triggers of bond crises in small frontier and emerging markets. Add up the creative borrowing against assets by the previous regime and the number balloons to circa 40 per cent. At current valuations and GDP numbers, that accounts for anything between $US20 -30 billion outstanding held overseas. And this is an overly pessimistic estimate. The actual numbers should be much lower. That puts our foreign currency liabilities at 50 per cent of GDP.

A seminal paper on the appropriate debt threshold By Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff hypotheses’ that smaller economies get on a slippery path to debt deflation and default once foreign currency debt reaches 60 per cent of GDP. On that count, the country has little to worry about. Of course the total debt stock is never a problem as domestic rupee borrowings can be inflated away as done so wonderfully by successive governments since 1977. Above all else, Sri Lanka’s total debt outstanding is so small compared to global debt volumes that foreign investors can count on an implicit Indo-American put. As a political project that is important for the Indo-American relationship, the current administration will be rescued by the joint powers, should they face hostile bond holders.

What then is there for equity investors? Incoherent policies are bad for confidence at the best of times; to do so now is sacrilege. Breaking apart the equity risk premium for Sri Lanka since 2008, a significant driver was catch-up growth – spare capacity and idle assets that weren’t deployed for 30 years suddenly found a use. That finished in 2013. Quasi monopolistic businesses colluding with the government produced the next highest return component since 2013. Since January 8, 2015, a full six months prior to a major emerging market sell-off, Sri Lankan stocks came off the boil on two counts. One, the limits to growth in Sri Lanka are structural not cyclical as various actors of the government may paint it to be. The country has one of the poorest demographic profiles for a low/middle income country.

This isn’t going away. Second, and more important, domestic consumption was supported perversely by the rise in wealth of Arab countries off the commodity boom, which took in many Sri Lankan workers. The other major consumption driver was remittances by expatriates to Canada and Australia – again beneficiaries of the commodity boom. While the commodity bust has made input prices cheaper at the macro-level, micro-level consumption has been guttered by developments in key employment markets. Badly timed, poorly targeted consumption taxes have made matters worse. Equity investors will have to face both slowing consumption and weaker margin growth across all major sectors. Add a potential 30% depreciation of the Rupee to align it with its correct valuation and all indicators flash red.

What then is a viable Yahapalana investment strategy? Unsurprisingly, it’s no different to ‘thugocracy investment policy’ which would have tripled investors’ money under the previous regime that is frequently berated by the current government. Go long on crony capitalism’s asset class of choice – real estate. The distortion of the real estate market (especially in Colombo) is so bad, it’s worse than Hong Kong during its frothiest period in history. Political uncertainty in Maldives has helped this the most. But a closer look at sales and end ownership clearly show tax evasion and payment capture as driving forces.

If anyone considers that to be a worthwhile investment process to make future investments, you don’t deserve your capital back. Small steps to bring back confidence will go a long way for the government in multiplier effects to augment their hard efforts to rebalance the economy. Otherwise, they can’t fault investors for believing Jean-Baptistes’ epigram – “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” loosely translated – the more things change, the more they stay the same.

(Kajanga is a behavioural economist based in Sydney, Australia.

You can write to him on kajangak@gmail.com.)

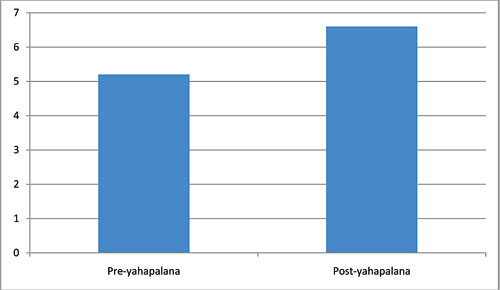

Data source: IMF database, Factset, JP Morgan EM Composite Bond Index The Yahapalana paradox! – Median coupon offered on US denominated bonds issued by the government of Sri Lanka and state owned enterprises pre and post yahapalana regime. If stated advantage of ‘yahapalana’ regime was to bring down borrowing costs, this is a strange turn of events. Debt raised after Jan 2015 has been 1.4 per cent more expensive.

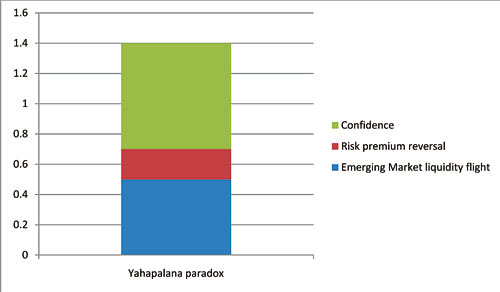

Figure 2: We broke the yield change into components using a proprietary behavioural model and analytical breakdown of the broader JP Morgan Emerging Market Index of which Sri Lanka is a constituent. Over 50 per cent of the rise in borrowing cost is directly attributable to the government.