Individual stories matter in the large canvas of suffering

“If I survived, it’s due first of all to chance, and secondly to the anger, the will to unveil those crimes, and, finally, to a coalition of friendship, for I had lost any visceral wish to live.”

“If I survived, it’s due first of all to chance, and secondly to the anger, the will to unveil those crimes, and, finally, to a coalition of friendship, for I had lost any visceral wish to live.”

Looking at recent academic works on Nazi extermination camps, it is sometimes saddening to notice how the primary sources have vanished. These are the first hand witnesses who were human beings with potential to bear extreme physical suffering and this can be felt as an affront to our duty of memory. Among such witnesses were the French victim cum social scientist and researcher Germaine Tillion, and the German militant, also a victim, activist and author Margarete Buber-Neumann.

Germaine Tillion (1907-2008) was an academic in the field of anthropology, who specialised in colonial Algeria as early as in the 1930s. She was a social researcher, turned resistance fighter against Nazi occupation in France and historian of the Nazi concentration camps, and, not least, a despairing negotiator between Algerian ‘terrorists’ or liberation fighters and the repressive French colonial state in Algeria.

Germaine Tillion was born to a middle-class French family in 1907. She followed the lectures of Marcel Mauss, founder of French ethnography and the nephew of Emile Durkhein, himself the founder of French sociology. Working with the Musée de l’Homme (‘The Museum of Mankind’) in Paris, she conducted fieldwork for six years in remote Algeria with funds from the International African Institute, London.

When the Second World War broke out, she hurriedly returned to France to take stock of the situation in her country which had been invaded by the German army. As a patriot she immediately joined the underground Resistance against the Nazis. However she soon realized that this was also a civil war, with French collaborators joining the German oppressors to repress French opponents: “There is the man who prefers to die rather than to betray, and the one who prefers to betray rather than to die; two races,” she said. She often tried to identify strength and weakness in man; but refusing to consider any specification on the supposed differences of races – she defined herself as a humanist and universalist.

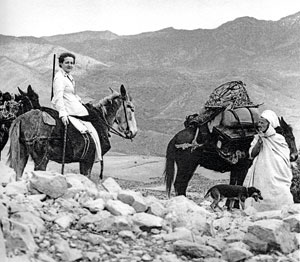

Germaine Tillion with her mother

In 1942, along with her mother, she was betrayed by a French priest. They were arrested and separately interned at the Santé prison in Paris. Here torture by the Germans was rife but so was solidarity between the detained women. Sentenced to death under 15 charges, she was eventually sent to the concentration camp of Ravensbrück (‘Raven’s Bridge’) in Germany. Her mother would unfortunately follow.

Germaine Tillion faced extermination but still tried to analyse on the spot the process of the Nazi system: “If you understand what crushes you, you sort of dominate it,” She explained it to her co-detainees. One day Germaine Tillion and her mother were on the list of those to be immediately transferred to the adjoining camp – the gas-chambers. That day, Germaine Tillion, was sick and in the infirmary. She narrowly escaped, thanks to the German woman prisoner also lying sick there and who offered at the risk of her own life to hide her under the blanket: this woman was Margarete Buber-Neumann, a German Communist militant who had been deported on Stalin’s order from Siberian camps to Germany. Protected by the other women, Germaine Tillion continued to take notes and she even wrote a short opera which she sang to the others. This went on until she was freed through Swedish Red Cross intervention before Hitler’s fall. She had escaped and she would never forget. Her mother had died in the gas-chambers. Her grandmother, aged 94, had died at their home near Paris only a few months before.

After the war Germaine Tillion concentrated on collecting testimonies about the concentration camps and collating them from former co-detainees, including the names and stories of each of those who did not survive, victims of the terrible suffering deemed necessary for the practical functioning of the system in place as elaborated by the Nazis. At that time she also followed the trial of war criminals, both German and French: “I hate them but I also feel pity towards them, and this makes me sick”.

She wrote three versions of her book about Ravensbrück. She was confronted with what she called “historical refraction”, appalled by the fact that Nazism was being now analysed through a sort of generalization rather than through individuals’ stories – the stories of so many sufferings.

Even though she understood that justice and history could not take the individual into account, she felt that something was lost and she rebelled: “Each agony was an individual one – and it is wrong to think that with ten crimes we can understand one hundred of them.” Both she and Margarete Buber-Neumann in post-war Germany continued to research and write on the subject.

Germaine Tillion started working again on Algeria. But the war of liberation broke out in Algeria and in France. At the height of that war, she was invited by top ranking organisers of the main liberation movement to intercede as a negotiator – which she did tirelessly. Although she was French and a patriot, she felt that “our motherland is dear to us on the condition of not scarifying truth.” “France, she argued with authority, does to the Algerians what the Nazis did previously to us.” Moreover, she realized that the so-called ‘terrorists’ acted in many ways as she had done with her friends in the Resistance movement in France 15 years previously. She succeeded in saving the life of dozens of Algerian militants. Among them, Yacef Saadi, top rank leader, who later became the producer of the well-known movie The Battle of Algiersdirected by Gillo Pontecorvo. The film was released in 1965, but banned in France for 40 years. It is said that some 50 years after being saved by her, Yacef assisted Germaine Tillion whilst she was on her deathbed in 2008, aged 101.

Germaine Tillion carrying on her work for justice in French occupied Algeria

Last May, 2015, Germaine Tillion and her colleague and friend Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, who had also been interned at Ravensbrück, both Resistance women, were solemnly and symbolically buried at the Pantheon. The Pantheon is the secular mausoleum on the top of a prominent hill in Paris hosting in its huge crypt the mortal remains of dozens of distinguished citizens of France among them Victor Hugo and Emile Zola, both 19th century writers and social activists; the 18th century philosophers Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire; and also Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie – the only woman until last year.