She dared compare poverty to life in concentration camps

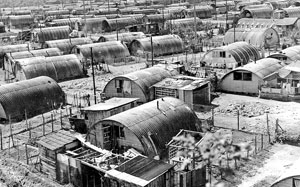

Shanty town in Noisy le Grand

“Heroism? I don’t like this word. People need role-models, so we invent heroes for them. But that’s not life. I don’t think we need to go for a great life or a great destiny. We just need to do our best to respect justice.”

In May 2015, the late Genevieve de Gaulle-Anthonioz (1920-2002) officially entered the Pantheon, the French secular mausoleum and ‘hall of fame’. The soil from her grave was taken there along with Germaine Tillion’s. A symbolic gesture as in both cases the families were opposed to the transfer of the real bodies to the Pantheon.

Both women were Resistance activists fighting against the German occupation from 1940; both were arrested in France and kept in solitary confinement, and both were friends in adversity in the Nazi concentration camp at Ravensbrück. They both survived and remained friends for 50 years.

Genevieve de Gaulle was born in 1920. The niece of General Charles de Gaulle, she was from a French Catholic family. She studied in Brittany, then in Paris at the start of the war.

At the age of 19 she joined a group of underground Resistance fighters against the German occupation. They were all betrayed by a member of their network who was in fact working for the German occupation forces. Genevieve was arrested in July 1943. She was kept in isolation for six months in a jail near Paris before being transferred to the concentration camp of Ravensbrück in Germany in January 1944. There she spent more than a year. Germaine Tillion and her mother Emilie Tillion were at the same camp.

“While we were walking and staggering along between the dark barracks of the camp, I was obsessed by the certitude that, much worse than death, it was the destruction of our soul which was the basic project of the concentration camp system,” wrote Genevieve de Gaulle, fifty years later.“Never in my prayers would I have accepted to be kept aside from the most miserable of these women, the ones who would steal bread, who would beat us for soup, or even worst, who would stay laying in a corner amidst their vermin and their stain. They were portraying what we were on the verge of becoming, and I felt I had to take my share of their humiliation, the same way we share fraternity or bread.”

Provocative and daring, she also knew the German language, and was proud of her uncle, General Charles de Gaulle, who led the French rebel forces fighting against German occupation. She was freed by the Russians when the camp was invaded by the Red Army in April 1945.

It was only quite recently that she wrote a book on her experience of the camp. It was published in 1998, a few years before she died.

The young Genevieve

In 1946 she married Bernard Anthonioz, a young editor of her age – while they were working on a compilation of testimonies from the camps. “We had immediately thought of Germaine Tillion as she had understood that the extermination camps and the labour camps worked in synchronisation. Those sentenced to extermination were supposed to bring in a profit, and those sentenced to work had to be exterminated – the whole system brought considerable profit to the Nazi leaders.” The women were exploited and condemned to disappear. Often, when Genevieve remembered the life in the camp and the exceptional friendship and solidarity between the women prisoners, she was reminded of how much suffering it cost to achieve that feeling of humanity – within the context of sheer barbarism.

During the 1950s she looked after her four children while continuing to be a militant for Charles de Gaulle’s political party. But in 1958, she met ‘Father Joseph’, listened to his accounts, and heard about his actions. Fr. Joseph Wresinski (1917-1988) was a former Communist militant turned Catholic priest who worked all his life for the economically destitute, excluded from society and marginalized, living in shanty towns around Paris. The encounter with these people who were totally deprived was a turning point for Genevieve de Gaulle-Anthonioz. “The expression which I read on their faces was the same that which I had read long ago on the faces of my comrades in the concentration camp. I could read the same humiliation and despair in a human being fighting to keep a minimum of dignity.”

She is the only one who dared compare extreme poverty in our contemporary society to the extermination camps. She would work in solidarity with these people for the rest of her life, becoming the active President of Fr. Joseph’s organization, Help for All Distress – Fourth World (ATD – Quart Monde) which became an international movement.

The Nazi concentration camps were not merely there to suppress people – but also to make the same people feel humiliated to the extreme and to deprive them of their most basic dignity. Genevieve de Gaulle-Anthonioz understood the same process of oppression among the lumpen-proletariat, and her life became a permanent fight for justice and for the dignity of the others. In that sense she was not a hero – but a responsible citizen.