A night with renal colic

View(s): By Dr. Susil W. Gunasekera

By Dr. Susil W. Gunasekera

Around 2 a.m. I was woken by cries of pain and loud thuds on my door. They were coming from the welder sleeping on my verandah. Opening the door I rushed to him. He was in agonizing episodic pain –suffering sporadic bouts of pain.

He wouldn’t let me touch his body to locate the pain site. Amidst his distressing pain and curses, I got him into my car and drove to the nearby hospital. The porter placed him on a wheelchair and wheeled him to the OPD Doctor on duty.

By 3 a.m. he was in agony. After a brief physical examination, he was wheeled to the Surgical Ward. A painkiller suppository calmed him down. The attending doctor needing further diagnostic guidance called the Registrar of the ward. Within minutes he arrived, examined the patient and arrived at a tentative diagnosis: ‘Renal Colic’. He ordered the necessary diagnostic tests. The medication sedated the patient to deep slumber. I returned home. Most of what needed to be done had been done.

The patient returned home by 6 p.m. the next day with a grin on his face. The clinical and diagnostic records he brought along with him indicated no renal stone in his urinary system. It is likely that the stone had been dislodged and passed out in the urine.

Renal colic is a medical term. Renal colic is signalled by a sharp, severe agonising pain in the lower back over the kidney, radiating forward into the groin.

Kidney stones (calculi) typically leave the body in the urine stream, and a small stone may pass without causing symptoms. If stone grows to a sufficient size (usually at least a diameter 3 millimetres), it can cause blockage of the ureter. This causes pain, most commonly beginning in the flank or lower back and often radiating to the groin or to the inner thigh. This pain is known as‘renal colic’ and typically the pain comes in waves lasting 20 to 60 minutes.

Kidney stones (calculi) typically leave the body in the urine stream, and a small stone may pass without causing symptoms. If stone grows to a sufficient size (usually at least a diameter 3 millimetres), it can cause blockage of the ureter. This causes pain, most commonly beginning in the flank or lower back and often radiating to the groin or to the inner thigh. This pain is known as‘renal colic’ and typically the pain comes in waves lasting 20 to 60 minutes.

Renal colic usually accompanies forcible dilatation of the ureter, followed by spasms as the stone is lodged within the ureter or passes through it. Severe, intermittent periodic pain in the loin is caused by the spasmodic muscular efforts to force the obstructing calculus, downwards.

True to the adage, “Once a stone former – Always a stone former”, this welder had a repeat episode, some months later. The scenario was an exact replica of the first attack. After a hard day’s work, he retired to sleep, to be awakened at dead of night. He experienced identical signs and symptoms of the previous attack: restlessness and excruciating intermittent pain that radiated from the flank to the groin (the inner thigh). Rushed to the nearby hospital in the early hours of the morning he received treatment as before and returned the next day.

Are these episodes likely to recur? Most probably, yes, with associated symptoms including nausea, vomiting, fever, blood in the urine, pus in the urine, and painful urination. Blockage of the ureter can cause dilation of the kidney leading to decreased kidney function (renal function).

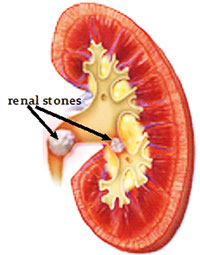

Renal stones or calculi

Kidney stone, also known as renal-calculus (nephrolith) is a solid, stone-like structure. These are formed out of chemicals in solution in the urine. The key to formation of renal stones is super-saturation of stone-forming chemicals (calculogenic chemicals) in the urine.

Chemical analysis of renal stones (as done in Medical Testing Laboratories) reveal that the composition of renal stones are those chemicals usually present in the urine: Calcium Oxalate is the commonest constituent of renal stones in Sri Lankans. Calcium Phosphate, Triple Phosphate and Uric Acid stones are not unusual. Thus, the chemical composition of renal stones varies. Calcium and oxalate are our dietary ingredients. The oxalate moiety can come from our dietary vegetable matter (exogenous oxalate). Oxalate is also formed within our body (endogenously formed oxalate) by the conversion of vitamin C.

To provide preventive advice, we have to know the factors that contribute to renal stone formation. Such factors are known as ‘predisposing factors to urolithiasis’. These factors are genetical and environmental. An overlap of the genetic factor together with environmental factor/s increases the vulnerability to urolithiasis.

A man with a family history of renal stone disease (genetical), working in a hot environment, not drinking enough fluid and ingesting oxalic acid rich vegetables (environmental) is a likely candidate for renal stone disease. Another individual with a family history of uric acid stone disease, hyperuricaemic (elevated blood uric acid, genetical) and consuming animal organ meats (environmental) is a candidate for uric acid urolithiasis. Persons who develop urinary tract infections frequently, and are inadequately hydrated are likely to form triple phosphate stones.

Urinary acidity or alkalinity are also factors determining the type of stone. Alkaline urine impedes calcium oxalate or uric acid urolithiasis. During my days in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, teaming up with Dr. A.M.L. Beligaswatte, the then Consultant Urologist of the Teaching / General Hospital Kandy, I developed a test to determine whether urine is ‘lithogenic’ or non-lithogenic. The test based on the scientific principle embracing the Law of Mass Action stood the test of time. This test filters out stone-former from non-stone-forming healthy individual.

Since then (1985) I offered this test to seekers: – likely stone formers and patients who underwent treatment for renal stone disease. The test finding lithogenic urine (+) and typing of the chemical nature of lithogenic compound in urine assisted in instituting measures to avert recurrence of renal stone disease. The test is least bothersome. It requires a reasonable volume of first morning urine (first void).

Common sense precautionary measures

Preventive measures apply to the type of stones likely to be formed. So it is important to get a urine test done to find out the type of lithogenic material likely to saturate the urine.

Water intake and diet can have a profound influence on the development of kidney stones. Preventive strategies should aim at reducing the excretory load of calculogenic (stone forming) chemical compounds.

Measures to minimise formation of kidney stones:

Increase total fluid intake to ensure a daily urine output of more than two litres

Ensure inclusion of lemon/lime juice in food and drink to prevent urine-calcium super-saturation

Keep supplemental calcium intake (with Vitamin-D) at a moderate level

Lower salt intake to lessen sodium intake

Avoid ingestion of large doses of supplemental Vitamin-C

Cut down animal protein intake to prevent urine acidification

Severely curtail consumption of cola soft drinks to lower phosphate intake.

Maintenance of dilute urine by drinking enough water averts all forms of urolithiasis. Therefore, increasing urine volume is the key principle for prevention of kidney stones. Fluid intake should be sufficient to maintain a urine output of at least 2 litres a day.