Lessons in caring and patience

View(s):A daughter recounts her experience of taking care of her mother diagnosed with a terminal illness, during her last years

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

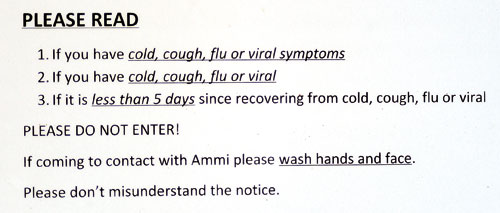

Memories and memorabilia: Her parents wedding photograph and her mother's walking sticks. Pix by Amila Gamage

The mother was in Sri Lanka and the daughter was half a world away in America. The first pointers that all was not well with the mother came from her letters.

Whereas her letters were beautifully written earlier, the daughter saw a gradual deterioration in her mother’s handwriting. Her writing would be large at the start and become smaller, sometimes going in circles in the same place. What the daughter did not know at that time, when she noticed it, was that it was a common symptom of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. (PSP –is an uncommon brain disorder which affects movement, gait, balance, speech, swallowing, vision, mood, behaviour and thinking).

The balance issues came later, she says, whenever her mother stood up she would feel as if she was swirling and had to pause awhile before taking a step. By 2008, she was having falls and coordination issues as well as memory issues. The daughter was shocked at her state when she paid her a visit in America the same year. Her mother who was 67 years old and had been very independent was totally dependent and unsure of herself.

First diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, it was much later that the doctors zeroed-in on PSP. It was then that the daughter took a major life-changing decision – she would give up her job in America and come home to be with her mother and look after her.

MediScene gets a first-hand look at how the daughter-turned-carer gave of her best to her mother in her last years.

Her first priority was to prevent falls, for a major fracture would mean becoming bedridden. It meant that the person who initially used a walking stick, had to depend later on a walker while giving up the use of the toilet to a bedside commode.

Before moving back from America permanently in 2011, the daughter had joined a support group from which she garnered a wealth of information.

“My mother was very alert and had the ability to reason,” she says, pointing out that such a person’s carer should be someone very close to her. Her advice to anyone facing a similar situation is to find a good General Practitioner (GP) or Family Doctor who would be able to pay home visits while also being easily accessible all the time. Such a GP would not be rushed and spend time with the patient while advising and guiding the patient’s kith and kin on the different kinds of Specialists who would have to be consulted over the years, depending on the need.

When caring for a person suffering from PSP, regular checks need to be carried out with regard to the sugar and cholesterol levels, as well as the lungs as a common ailment could be pneumonia. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) could also cause a lot of trouble.

Each patient with PSP or any other terminal illness would be different, she says, adding that it is an individualistic disease. This is why it is important for the carer to observe the symptoms closely.

She advises other carers that a contingency plan, in consultation with the patient, has to be in place from the beginning – in case the patient needs hospitalization, what would be the preference, who are the doctors who would be called in, what are the interventions that would be acceptable. “My mother was adamant that she would have no nasal or peg-tube feeding. Neither did she ever want a catheter, all wishes that I honoured scrupulously.”

This was while she personally managed the medication regimen through observation of the strengths and weaknesses of the medications when given to her mother. This also helps the patient, as medications are just one-fourth of the battle, according to this care-giver who looked after her mother for four years.

When one is in the long haul with a terminal illness, the care-giver has to observe and take decisions. Usually, medications help in the management of the patient about 20%. This is why it is important to observe the reaction when medications are given and take decisions after considering the individual needs of that particular patient.

A pretty garden to ease the stress

Domperidon given half-an-hour before a meal, helped her mother overcome the troublesome reflux issue, while control of the zinamet dosage was important to prevent her from feeling drowsy all the time. When she took her mother off rivaden, the zombie-like state she was in most of the time, heavily drowsy and sleepy, could be warded off.

“Some carers like to keep their patients heavily medicated as it makes their life easier, but I chose not to do that,” she says.

Underscoring that the environment is important, she speaks of how she improved their home with tiny touches here and there. A little garden to feast the weary eyes on was just one such example. “A care-giver needs to please her eyes and mind, as otherwise she will feel cooped up in dusty and dingy surroundings and will end up with depression.”

Referring to physio, occupational and speech therapy, she is quick to point out that it is a slow process but needs to be carried out regularly. When choosing the therapist, it is important to ensure that the person has adequate time to spend with the patient. The patient needs to be given time to express herself which may take a long time in speech therapy which is vital to slow the progression of the throat muscle breakdown. “The less the patient talks, the faster the throat muscles deteriorate, impacting heavily on the food and drink intake.”

There needs to be reading and singing and even though one by one these activities taper off, the patient should be encouraged to do whatever she is capable of doing. Occupational therapy helped in her mother’s case to write many things she would otherwise have forgotten and also keep track of how the day goes. For depression can be prevented if the patient can express herself.

There needs to be reading and singing and even though one by one these activities taper off, the patient should be encouraged to do whatever she is capable of doing. Occupational therapy helped in her mother’s case to write many things she would otherwise have forgotten and also keep track of how the day goes. For depression can be prevented if the patient can express herself.

Physiotherapy is vital to keep at bay the muscle-breakdown which is imminent. As muscles get stiff there is a need for continuous toning, as otherwise movements get limited very fast. Exercise, meanwhile, should not be done beyond the point of pain, while simple home remedies such as fermentation, hot and cold, and massages could also be performed.

This daughter relives the relief her mother would feel when for knee pain or neck-stiffness, an oil massage would do wonders

If she is able to, let her get a cup of tea herself, after doing a small round independently even in a limited area which has been adjusted to meet her needs. Communication is of utmost importance, if possible until the very last, she says.

Pointing out that sometimes when visitors come, they assume that just because the patient cannot talk, she does not understand is a huge misconception common in our society and many have been the times when this daughter has had to point out that her mother can hear and understand everything very well.

This care-giver has a strong belief in ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ foods and drinks. She would feed her mother mung (green gram), nivithi (spinach) or bandakka (ladies’ fingers) usually before noon, while she realized that a cough would get triggered if she gave her mother mango-lassi which she loved. However, thal-sukiri pre-empted the cough. Bathala (sweet potato) and wattakka (pumpkin) resulted in constipation in her mother, a drop of ginger juice prevented phlegm and pol-pala and akkapana worked wonders for urinary tract infections.

Vociferous about not taking away the joy of eating from her mother, she had to drastically change her food pattern when the throat muscles began to falter. There followed smaller portions and more liquids and later lots of efforts and also sometimes loss of patience to get some nourishment into her mother’s system.

She reiterates the importance of humour, whenever she lost patience when attempting to feed her mother. She would lighten the mood with a joke and both mother and daughter would chuckle over it. For feeding was a serious business as the throat muscles packed up and the risk of aspiration increased.

As the care-giver, this daughter looked at every tiny detail – her mother’s dental care, insisting on brushing her teeth and rinsing her mouth and making sure that when swallowing difficulties developed, saliva and phlegm would not collect in her mouth.

Looking into her mother’s eyes, she also saw blephalitis, common in the elderly, developing in her too and attended to it, while with constant diaper-use, an angry red rash resulted, overcome by inserting a paankada kella (piece of cloth) between the diaper and the skin.

Now that her mother is no more, this daughter-carer looks back on the past four years with contentment. “Life went back to basics and being simple,” she says. “It was the best education in patience that I got in my whole life, while just looking after my ‘needs’ rather than my ‘wants’.”

She adds: “Looking after my mother was a great opportunity granted to me…….it was a blessing.”