The art of the Naturalist

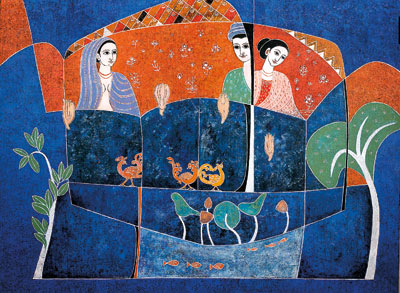

A piece from a new series of modern abstract works containing elements of temple painting and sequential storytelling

In the 1990s, artist Channa Ekanayake left Colombo and journeyed to the Anuradhapura district, to find out for himself what the Eppawala phosphate mining controversy was about. Extensive phosphate mineral deposits had been discovered in the area and the government was on the verge of selling off hundreds of acres of land to an American-based multinational, placing entire villages, ancient artefacts and irrigation systems and traditional sustainable ways of life at risk. A protracted fight for rights by the villagers threatened by the development was gathering momentum in the heart of the country.

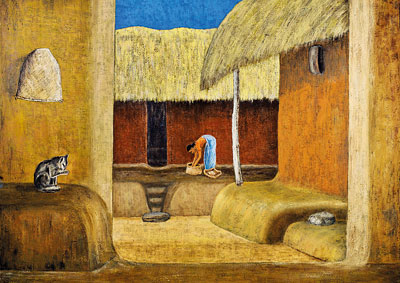

In Eppawala, he came across idyllic villages. The simple harmonious dwellings, constructed with materials from the immediate environment, captivated him. Their design, customised to the needs of the occupants, fascinated him. He lingered on and became a grassroots activist. He began to capture the villages on canvas; sublime pastoral scenes in earth tones celebrating moments of harmony between mankind and nature. The peaceful depictions of day-to-day life, temples, fields and livestock and landscapes projected a lifestyle where nature had been tamed just enough to yield basic necessities.

Forty five paintings later, in 2001, he returned to Colombo, where at the urging of fellow activist, photographer Nihal Fernando, he held his first solo exhibition, Dwellings, at the Lionel Wendt to raise awareness of the Eppawala crisis in Colombo. Some 87 villages in a 56-square kilometre block had been earmarked for initial mining. More were to follow and a disaster was looming.

For Channa, Dwellings was not only an urgent impulse to prod Colombo, but an opportunity to capture childhood memories.“I am from Hanguranketa, Katugastota,” he says. “In the ‘50s and ‘60s, there were similar clay houses there. The houses came together with the memories and became the central theme of my art.”

On a personal level, Dwellings revisited the innocence, simplicity and warmth of his childhood environment. On a national level, it raised awareness of a culture under threat. Not confrontational, every piece conveyed the artist’s guiding philosophy, harmony, through the selection of colours and the balance of elements that gently led the viewer into the heart of the composition. Thirty-one of the 45 works sold.

Turning points in life

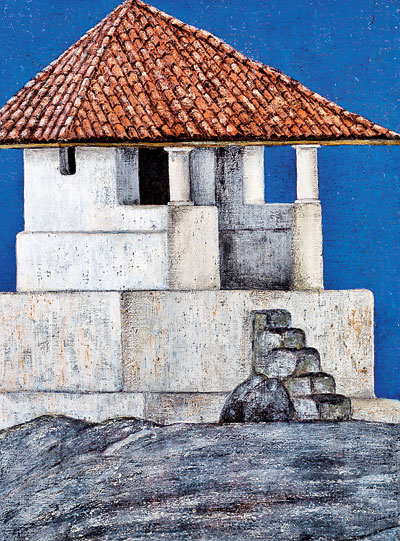

Rustic village shrine. If you dig a little deeper you will find nature in the colours and the subject matter, like the rocks, the clay bricks and the blue sky. Pix by Rasika Surasena

In time, the Eppawela campaign came to a head. A group of representatives lodged a court case that resulted in a landmark ruling against the scheme. It was a transformative experience for Channa. For the second time in his career, a major shift occurred: “I became more simple, non materialistic. I started staying at home. I became environmentally aware and concerned. I began to study nature and biodiversity. I read up on birds, butterflies, snakes, lichens… you have to learn about nature to understand it.” Travel and visits to remote areas and jungles became a common pastime.

His first shift was from teaching to art. A graduate of science and literature from Peradeniya University, he was teaching O’ Level Sinhala when he resigned to focus on painting. Literature inspired his art, as did nature.

He studied art at school and under veteran artist Sumana Dissanayake. Then he learned from Croatian artist Dora Tomulic-Aluwihara who encouraged his individual style and interpretation and taught him the value of tonal variations and the Golden Ratio for harmony; fundamentals he will not veer away from even today. He drew inspiration from Sri Lanka’s Ivan Pieris and Druvinka, and Pakistani artist Jamil Nasq. English artist Ben Nicholson’s minimalist geometrical and abstract style was a key influencer.

The art is the artist

We are in Channa’s living room, large, airy and open, overlooking lush greenery. The doors and windows are wide open. He has built a cavity wall across the living room to direct the airflow into the house. Artworks, old and new, are on the walls. A few pieces from Dwellings remain.

After Eppawala, Channa’s work became sequential narratives of idyllic existences. In one storyboard-like work, the sun rises, a girl feeds her bull, lies down at noon, picks fruit for the animal, and at sunset serenades it with flute.

Complementary colours orange and blue, prevail. There are also earthy tones like ochre and sienna that belong to the same family. White and black add contrast. He works with a variety of mediums: oils, acrylics, gouache, pastels, and egg-tempera. Nature’s palette doesn’t always cross over into his canvas. “Since there are so many trees around me, I always get rid of green in my paintings,” he says.

His most recent works are vibrant, detailed but abstract, with motifs inspired by temple paintings. Geometrical shapes, stylized figures, leaves, flowers and trees, and the crimson red that is a common background in temple painting feature. “I wanted to use those traditional elements in a modern abstract composition,” he says. There is another new series of stark subjects singled out for an earthy textured study.

While he regularly participates in group exhibitions here and overseas, Dwellings was his only solo exhibition. “I don’t need solo exhibitions because I have a home gallery. People come here … That’s enough,” he says. “It leaves me time to concentrate on gardening, visiting forests, and so on.”

These days, the desire to live and work with nature has begun to take precedence over art. You could now call him a naturalist rather than artist.

One of the 45 works based on village life in Eppawala shown in Dwellings, his first and only solo exhibition

Of art and nature

Presently, man and the environment are not in balance. Can art help restore the equilibrium? All colours and materials come from nature, so there is a strong bond between art and nature, he says. Nature is also in the subject: if you dig a little deeper, you will find that whatever we draw arises from nature; all the shapes we ultimately use come from the human body or from other natural features …. clouds, rocks etc.

The golden ratio abounds in nature; in the way the branches of a tree split and branch out, and in the petals of a flower, in the arrangements of the seeds in a sunflower, or on the shell of a snail. It is the basis of perfect harmony.

Texture is also connected to painting. “Nature has different textures; rough and smooth. Texture is very important, because that’s what photographers cannot do. The invention of the camera enabled photographers to do what artists had done in a more clever and quicker way. But a photograph is always smooth, whereas a painting, like nature, can convey a textured tactile experience.”

Some say nature is the best artist. Yes, he says. But if there is no human eye to understand nature’s aesthetics, would it be called a work of art?

He narrates a tale: In a village in Russia, there was an annual prizegiving for the best sculpture. One year, the top prize was awarded for a rock salt sculpture. The panel of judges marvelled at the variety of shapes the work yielded from various perspectives. When the judge finally called for the sculptor, a farmer led her cow onto the stage. The entry had been licked into shape by a cow! It was disqualified. And then nowadays there are elephant “artists” whose works sell at very high prices. Even if nature is the best creator, humans are the arbiters.

The naturalist’s garden

Channa’s home is surrounded by a small, forested compound, a micro habitat, home to dozens of indigenous trees, bushes and vines and creatures that thrive among them.

He explains the richness of its bio-diversity. Every plant here nourishes a creature. The sap sanda vines, for example, feed the larva of the Sri Lanka birdwing, the crimson rose and the common rose; the wel penela and olinda vines, the blue cerulean butterfly. Cerulean pupae incubate in the fallen leaves, which is why the dead leaves should not be swept away. Leaf litter remains under the trees, turning into fungi that are an important food source for frogs and other creatures. He points to holes that are homes to snakes. A pool draws mosquitoes that feed the fish. The fly catchers in the garden feed on adult mosquitoes.

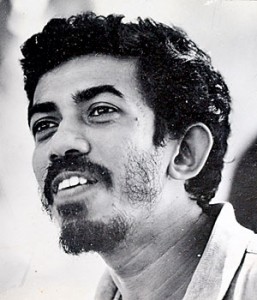

Channa Ekanayake

There was a day when Channa walked down the road with a diyabariya (common water snake) from the pond latched onto his finger. It swam away when he dipped his hand into the ella before returning home to attend to the bite. The snake is not venomous. A hole in the boundary wall leading to an overgrown neighbouring plot allows bandicoots to visit the garden at night, and monitor lizards to lumber in during the day.

Large forest trees and saplings grow in the compound. Won’t it upset the foundation of the house? “How long can you live?” he asks. “When you plant a tiny plant, it becomes a huge tree after 80 years. What’s the point of worrying about whether it will damage your house after 80 years?”

What of the children? “They have their own life. Who knows whether they will live in Sri Lanka? Think about one generation; all the troubles in the world are because we are collecting for future generations. The Buddha said, ‘Live a day at a time.’ If only we can obey that teaching, we can have a happy life! This is the reality of life, so let the other creatures also live.”

Nature’s golden rule encrypted in Channa Ekanayake’s sublime art echoes man’s need to strike the fine balance that is crucial for harmony.

This abstract of interior perspectives shows the influence of British artist Ben Nicholson